3.1 Introduction

This chapter examines the ways in which major element data are used to understand the genesis and evolution of the major rock types. Here we discuss the role of the elements Si, Ti, Al, Fe, Mn, Mg, Ca, Na, K and P – the 10 elements that are traditionally given as oxides in a major element chemical analysis – but do not consider in any depth the volatile elements H, CO2, S or N. Although we recognise that the volatile elements play an important role in understanding the evolution of our planet in terms of chemical mass-balance through volcanic degassing and hydrothermal alteration, a full discussion of these themes is beyond the scope of this text and the reader is referred to other sources (e.g., Luft, 2014). For a detailed discussion of the major element chemistry of the oceans, again we refer the reader elsewhere (e.g., Millero, 2014).

This chapter is concerned with the three principal ways in which geochemists make use of major element data:

The combination of major and trace elements can often be used to identify the original tectonic setting of igneous and some sedimentary rocks, and this topic is addressed in Chapter 5.

The application of major element chemistry to rock classification and nomenclature is widely used in igneous petrology and can also be useful for some sedimentary rocks. Variation diagrams display major element data on bivariate or trivariate plots. These diagrams are used to show the interrelationships between elements in a dataset and from these relationships geochemical processes may be inferred. Variation diagrams based upon trace element concentrations are discussed in Chapters 4 and 5. The third use of major element data, plotting the chemical composition of an igneous rock onto a phase diagram, assumes that the chemistry of the rock is the same as that of the original igneous melt. In this case the comparison of a rock composition with experimentally determined phase boundaries for melts of similar composition under a range of physical conditions may allow inferences to be made about the conditions of melting and/or the subsequent crystallisation history of the melt.

However, before major element data are used in any of these ways it is important that the data are evaluated for quality and are processed in a uniform and consistent manner. In particular, it is important that the oxidation state of Fe is treated uniformly, that analysis totals are normalised to exclude the presence of volatiles and that a decision is made about whether the data should are presented as weight percent oxide or as cations. Here we propose a standardised method of data processing to allow a better comparison between data generated using different methods and/or in different laboratories.

3.1.1 Processing Major Element Data

The first step of any geochemical investigation is to assess the quality of the data to be used. A petrographic evaluation of sample thin sections is helpful for this and allows any alteration products to be identified. Data quality can then be evaluated with respect to the relative proportions of primary and hydrous secondary phases, the value of the loss on ignition (LOI) and the analysis total. ‘Dry’ samples which contain no hydrous minerals or alteration products should have an analysis total between 99% and 101%, whereas ‘wet’ samples containing primary hydrous minerals or alteration products may have lower totals due to the loss of volatiles recorded as LOI. For example, island arc andesites are often water-saturated and commonly have primary amphibole, and may therefore have LOIs of 3–6% (Ruscitto et al., 2012; Plank et al., 2013). In such circumstances, and given the absence of petrographic alteration, low totals because of high LOI may be acceptable. In this case it is good practice to normalise the data on a volatile-free (anhydrous or dry) basis.

The next step is to assess the oxidation state of Fe. This is usually governed by the method of sample preparation. Historically, when major elements were determined using solution chemistry, all the Fe was reduced to FeO and reported as such in the chemical analysis. Today major element analyses are generated by XRF and ICP in which samples are converted into a fused, homogeneous glass prior to analysis. If a graphite crucible is used during sample fusion, then all the Fe in the sample is reduced to FeO and the analytical result is presented as FeO. If a platinum crucible is used, all the Fe in the sample is oxidised to Fe2O3 and the analytical result is presented as Fe2O3. It is important to report Fe as it was analysed to allow others to fully assess data quality. This is normally done using the terms FeOT or Fe2O3T, or sometimes as FeO(tot) and Fe2O3(tot), to indicate that all the iron is reported in a single oxidation state. Note, however, that reporting all the Fe in a single oxidation state does not reflect the true chemical evolution of magmatic systems, which tend to become more oxidising as they evolve. This topic is discussed further in Section 3.2.2.3.

Finally, a decision has to be made about the format of the data and whether or not oxide data should be converted to moles or cations. This usually depends on how the data are going to be used. Current practice is to present major element chemistry for rocks as weight (wt.) % and to convert as needed to cations, cation % or parts per million (see Section 3.2.3), although the chemical composition of water is typically presented in molar concentrations.

3.1.2 Major Element Mobility

Before beginning to classify and investigate the petrogenesis of a suite of samples it is important to consider whether or not they preserve their original chemistry and whether they have been altered in any way. This typically involves chemical changes which take place after rock formation, usually through interaction with a fluid. These changes may sometimes be described as metasomatic. Major element mobility typically occurs during diagenesis and metamorphism or through interaction with a hydrothermal fluid. In metamorphic rocks element mobility may take place as a result of solid-state diffusion or melt generation and migration.

The mobility of major elements is controlled by three main factors: the stability and composition of the minerals in the unaltered rock, the stability and composition of the minerals in the alteration product and the composition, temperature and volume of the migrating fluid or melt phase. Element mobility may be detected from mineralogical phase and compositional changes that have taken place in a rock as a result of metamorphism or hydrothermal activity and from the mineral assemblages present in associated veins. Thus, careful petrography is an important tool in identifying chemically altered rocks. Scattered trends on variation diagrams are also a useful indicator, although chemical alteration can sometimes produce systematic changes which may mimic other mixing processes such as crystal fractionation. These apparent trends may result from volume changes arising from the removal or addition of a single component of the rock.

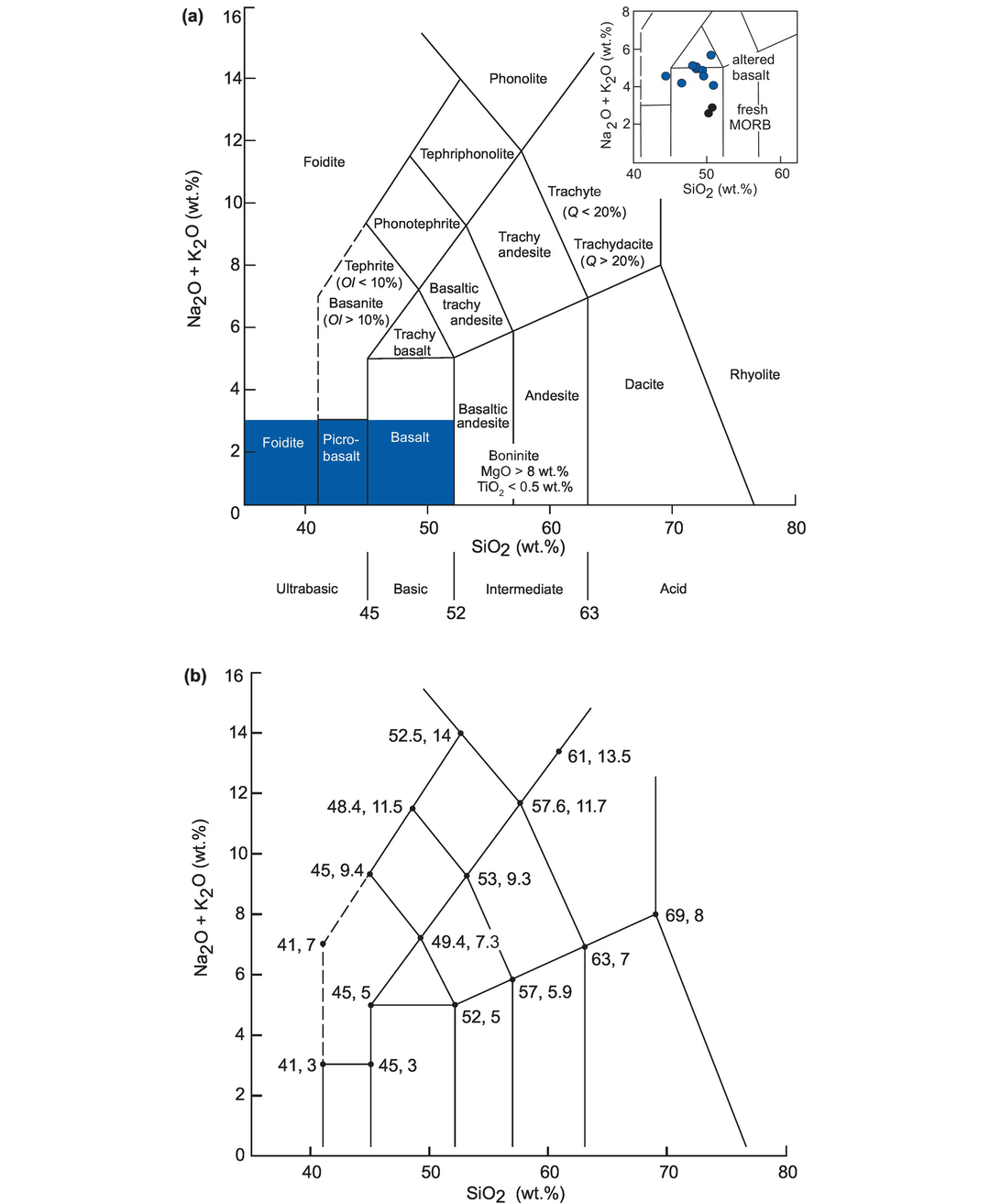

An example of major element mobility is given in the dataset presented in Table 3.1 in which a suite of Permian basalts from Sumatra has been analysed for the major elements. There are two unusual features about these basalt data. First, the samples have very high LOI, indicating significant hydration. This parameter alone can be taken as an indicator of possible major element mobility (e.g., Smith and Humphries, 1998). The Sumatran samples also appear to have very high Na2O contents relative to fresh MORB and MORB glass (Table 3.2b). When recalculated as anhydrous and plotted on a TAS diagram (see Section 3.2) the samples plot between basalts and trachy-basalts (inset, Figure 3.1a), suggesting that they are alkaline basalts. However, given their very high water content, an alternative explanation is that they have been altered by interaction with seawater and have thus become more sodic or spilitised. Further evidence for basalt alteration comes from the study of fluid-mobile trace elements, and this will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

The total alkalis versus silica (TAS) diagram for volcanic rocks. (a) The chemical classification and nomenclature of Le Maitre et al. (2002) after Le Bas et al. (1986). Q = normative quartz, Ol = normative olivine. Ol- and Px-rich rocks occur in the shaded region, which is expanded in Figure 3.8. The inset shows the possible Na-enrichment of Permian basalts from Sumatra relative to fresh MORB. (b) Plotting coordinates for the field boundaries expressed as ‘SiO2 and (Na2O + K2O)’ after Le Bas et al. (1986).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured compositions | |||||||||

| MR136 | MR137 | MR139 | IG5 | IG4 | MR150 | MR152 | MR153 | 95SM11 | |

| SiO2 | 45.13 | 44.82 | 46.31 | 37.60 | 46.01 | 42.70 | 43.64 | 40.76 | 48.03 |

| Al2O3 | 14.11 | 13.79 | 14.25 | 14.21 | 12.91 | 13.42 | 14.87 | 13.28 | 14.46 |

| Fe2O3T | 8.93 | 9.16 | 9.05 | 10.54 | 11.58 | 9.30 | 8.74 | 9.06 | 12.78 |

| MnO | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.19 |

| MgO | 7.34 | 8.75 | 7.34 | 6.54 | 7.08 | 6.32 | 6.34 | 8.37 | 7.74 |

| CaO | 10.88 | 8.95 | 7.36 | 9.89 | 6.16 | 10.04 | 8.32 | 10.90 | 7.92 |

| Na2O | 4.00 | 4.09 | 5.04 | 3.83 | 3.70 | 4.54 | 4.24 | 3.58 | 3.46 |

| K2O | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 1.10 |

| TiO2 | 1.29 | 1.42 | 1.32 | 1.31 | 1.70 | 1.57 | 1.33 | 1.19 | 1.35 |

| P2O5 | 0.68 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 1.29 | 1.22 | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.23 |

| LOI | 6.77 | 7.07 | 7.39 | 12.02 | 7.83 | 9.88 | 10.41 | 10.60 | 2.65 |

| Recalculated dry to 100% | |||||||||

| SiO2 | 48.43 | 48.38 | 50.41 | 44.25 | 50.76 | 47.81 | 49.24 | 46.29 | 49.38 |

| Al2O3 | 15.14 | 14.89 | 15.51 | 16.72 | 14.24 | 15.02 | 16.78 | 15.08 | 14.87 |

| Fe2O3T | 9.58 | 9.89 | 9.85 | 12.40 | 12.78 | 10.41 | 9.86 | 10.29 | 13.14 |

| MnO | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.20 |

| MgO | 7.88 | 9.45 | 7.99 | 7.70 | 7.81 | 7.08 | 7.15 | 9.51 | 7.96 |

| CaO | 11.67 | 9.66 | 8.01 | 11.64 | 6.80 | 11.24 | 9.39 | 12.38 | 8.14 |

| Na2O | 4.29 | 4.42 | 5.49 | 4.51 | 4.08 | 5.08 | 4.78 | 4.07 | 3.56 |

| K2O | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 1.13 |

| TiO2 | 1.38 | 1.53 | 1.44 | 1.55 | 1.88 | 1.75 | 1.50 | 1.35 | 1.39 |

| P2O5 | 0.73 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 1.42 | 1.37 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 0.24 |

| 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

3.1.3 The Compositions of Some Major Earth Reservoirs

It is sometimes useful for comparison or normalisation to have representative values of some of the major Earth reservoirs. These are summarised in Table 3.2 for the major elements and in Table 4.9 for trace elements. Table 3.2a shows major element compositional data for the whole Earth (or the bulk Earth), the silicate Earth (or the bulk silicate Earth, or BSE, a term interchangeable with primitive upper mantle, or PM) and the Earth’s core. The data are expressed in wt.% elemental concentrations and oxygen is shown separately. This is because the core contains no oxygen and so expressing the data as elemental concentrations allows comparisons to be made between the silicate Earth and the core. In addition to the 10 major elements present in most silicate rocks, the metals Ni and Cr and the light elements H, C and S are also included as they constitute a measurable fraction of the composition of the whole Earth. These data are from McDonough (2014a) and assume that the original undifferentiated Earth was similar in composition to carbonaceous chondritic meteorites. It is known that the Earth’s core contains a few wt.% of a light element in addition to Fe and Ni, and the McDonough (2014a) model presented here argues that the principal light element is Si, but that there is also some S present.

| Bulk Earth | BSE/ primitive mantle | Earth's core | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Si | 16.100 | 21.000 | 6.000 |

| Ti | 0.081 | 0.120 | 0.000 |

| Al | 1.590 | 2.350 | 0.000 |

| Fe | 32.000 | 6.260 | 85.500 |

| Mn | 0.080 | 0.105 | 0.030 |

| Mg | 15.400 | 22.800 | 0.000 |

| Ca | 1.710 | 2.530 | 0.000 |

| Na | 0.180 | 0.270 | 0.000 |

| K | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.000 |

| P | 0.072 | 0.009 | 0.200 |

| Ni | 1.820 | 0.196 | 5.200 |

| Cr | 0.470 | 0.263 | 0.900 |

| O | 29.700 | 44.000 | 0.000 |

| H | 0.026 | 0.010 | 0.060 |

| C | 0.073 | 0.012 | 0.200 |

| S | 0.635 | 0.025 | 1.900 |

| Total | 99.953 | 99.973 | 99.990 |

Reference: 1, McDonough (2014a).

| BSE/ primitive mantle | BSE/ primitive mantle | Depleted mantle | Mean MORB (whole rock) | Mean MORB (glass) | Mean continental crust | Mean upper continental crust | Mean middle continental crust | Mean lower continental crust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| SiO2 | 44.91 | 45.40 | 44.71 | 50.06 | 50.60 | 60.60 | 66.60 | 63.50 | 53.40 |

| TiO2 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 1.52 | 1.67 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.82 |

| Al2O3 | 4.44 | 4.49 | 3.98 | 15.00 | 14.79 | 15.90 | 15.40 | 15.00 | 16.90 |

| FeOT | 8.05 | 8.10 | 8.18 | 10.36 | 10.46 | 6.71 | 5.04 | 6.02 | 8.57 |

| MnO | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| MgO | 37.81 | 36.77 | 38.73 | 7.71 | 7.42 | 4.66 | 2.48 | 3.59 | 7.24 |

| CaO | 3.54 | 3.65 | 3.17 | 11.46 | 11.38 | 6.41 | 3.59 | 5.25 | 9.59 |

| Na2O | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 2.52 | 2.77 | 3.07 | 3.27 | 3.39 | 2.65 |

| K2O | 0.03 | 0.031 | 0.006 | 0.190 | 0.190 | 1.810 | 2.800 | 2.300 | 0.610 |

| P2O5 | 0.02 | 0.020 | 0.019 | 0.160 | 0.180 | 0.130 | 0.150 | 0.150 | 0.100 |

| Total | 99.46 | 99.16 | 99.19 | 99.17 | 99.65 | 100.11 | 100.07 | 99.99 | 99.98 |

| Mg# | 89.3 | 89.0 | 89.4 | 59.0 | 58.0 | 55.3 | 46.7 | 51.5 | 60.1 |

| Xenolith Average | PUM | PUM | PUM | PUM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| SiO2 | 44 | 45.96 | 45.14 | 46.2 | 44.92 |

| Al2O3 | 2.27 | 4.06 | 3.97 | 4.75 | 4.44 |

| FeO | 8.43 | 7.54 | 7.82 | 7.7 | 8.05 |

| MgO | 41.4 | 37.78 | 38.3 | 35.5 | 37.8 |

| CaO | 2.15 | 3.21 | 3.5 | 4.36 | 3.54 |

| Na2O | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.4 | 0.36 |

| K2O | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | nd | 0.29 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.38 |

| MnO | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| TiO2 | 0.09 | 0.181 | 0.217 | 0.23 | 0.201 |

| NiO | 0.012 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| CoO | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.012 | nd |

| P2O5 | 0.06 | 0.02 | nd | nd | 0.02 |

Table 3.2b provides the major element compositions of the major silicate reservoirs. The magnesium number (Mg#), its meaning and calculation are discussed in Section 3.3.2.1. As shown above, the primitive mantle is the same as the bulk silicate Earth – the Earth after the separation of the core but before the development of continental crust. Using the Earth reservoir data from Table 3.2a converted to oxide wt.%, the models of McDonough (2014a) and Palme and O’Neill (2014) are provided. The composition of the depleted mantle (DM) calculated by Workman and Hart (2005) is given for comparison and represents mantle from which some basaltic melt has been extracted. The DM, relative to PM, is more magnesian and slightly depleted in elements such as Ca, Al and Si which are preferentially incorporated into basaltic melt. A mean composition of over 2000 mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) samples from the floor of the major oceans is given and is very slightly different from the mean value of over 3000 MORB glass samples (data from White and Klein, 2014). Note, however, that these compositions simply represent what is found on the floor of the oceans and does not necessarily represent a primitive or primary MORB composition. The mean composition of the continental crust calculated by Rudnick and Gao (2014) is a weighted composite of the compositions of the upper, middle and more mafic lower continental crust.

Another important major Earth reservoir is the continental lithospheric mantle (CLM), often referred to in the literature as the sub-continental lithospheric mantle (SCLM) (see Table 3.2c). Fragments of the mantle provide our only direct samples of the CLM and include orogenic peridotites, ophiolites, and xenoliths transported via volcanism. Mantle xenoliths broadly define two compositional types: spinel- and garnet-facies peridotites associated with kimberlites, and spinel-facies peridotites associated with predominantly alkalic rocks. The former are generally found in cratonic settings and the latter in non-cratonic (rift) settings. Table 3.2c shows a compilation of xenolith and primitive upper mantle (PUM) model compositions from Pearson et al. (2014).

3.2 Rock Classification

With the advent of automated XRF and rapid ICP analytical methods most geochemical investigations produce a large volume of elemental data that allows for the classification of rocks on the basis of their chemical composition. This section reviews the classification schemes in current use and outlines the rock types for which they may be specifically suited. A summary of the classification schemes discussed is given in Box 3.1. We adhere to the guidelines of the International Union of Geological Sciences Sub-commission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks (Le Maitre et al., 2002) for the naming and classification of rocks. We concur that a classification scheme should be easy to use, widely applicable, have a readily understood logical basis and reflect as accurately as possible the existing nomenclature based upon mineralogical criteria.

Igneous rocks

3.2.1 Oxide-oxide plots

The total alkalis-silica diagram (TAS)

for volcanic rocks

for plutonic rocks

for discriminating between the alkaline and sub-alkaline rock series

Subdivision of sub-alkalic volcanic rocks using K2O versus SiO2

3.2.2 NORM-based classifications

Basalt classification using the Ne–Di–Ol–Hy–Q diagram

Granite classification using the Ab–An–Or diagram

3.2.3 Cation classifications

Komatiitic, tholeiitic and calc-alkaline volcanic rocks using the Jensen plot

High-Mg rocks using the Hanski plot

3.2.4 Combined major element oxide and cation classification for granitoids

The Frost diagrams

Sedimentary rocks

3.2.5 The chemical classification of sedimentary rocks

Sandstones

Mudrocks

Limestones

3.2.1 Classifying Igneous Rocks Using Oxide-Oxide Plots

Bivariate oxide-oxide major element plots are the most straightforward way in which to classify igneous rocks, especially volcanic rocks, and the principal diagrams are summarised below.

3.2.1.1 The Total Alkalis-Silica Diagram (TAS) for Volcanic Rocks

The total alkalis-silica diagram is one of the most useful classification schemes available for volcanic rocks. Using wt.% oxide chemical data from a rock analysis that has been recalculated to 100% on an anhydrous (volatile-free) basis, the sum of Na2O + K2O (total alkalis, TA) and SiO2 (S) are plotted onto the classification diagram. The original version of the diagram (Le Bas et al., 1986) was expanded by Le Maitre et al. (1989) using 24,000 analyses of fresh volcanic rocks (Figure 3.1a). Le Maitre et al. (2002) further expanded the classification to include olivine- and pyroxene-rich rocks (Section 3.2.3.3).

The field boundaries were defined by minimizing the overlap between adjoining fields, and the boundary coordinates are given in Figure 3.1b. The TAS diagram divides rocks into ultrabasic, basic, intermediate and acid on the basis of their silica content following the usage of Peccerillo and Taylor (1976). The nomenclature is based upon a system of root names with additional qualifiers to be used as necessary. For example, the root name ‘basalt’ may be qualified to ‘alkali basalt’ or ‘sub-alkali basalt’. Some rock names cannot be allocated until the normative mineralogy has been determined. For example, a tephrite contains less than 10% normative olivine, whereas a basanite contains more than 10% normative olivine (see Section 3.2.2 on the norm calculation).

The TAS classification scheme is intended for common volcanic rocks and should not be used with weathered, altered or metamorphosed volcanic rocks because the alkali elements can be mobilised. Potash-rich rocks (nephelinites, mela-nephelinites) should not be plotted on the TAS diagram, and ultramafic or high-Mg rocks (boninite, komatiite, meimechite, picrite) should be checked for their TiO2 contents before assigning a name from the TAS diagram (see Section 3.2.3.3). Rocks showing obvious signs of crystal accumulation should also be avoided.

3.2.1.2 A TAS Diagram for Plutonic Rocks

Of the various schemes for the naming of plutonic rocks, the two most popular ones based on major element chemistry are the TAS diagram for plutonic igneous rocks (after Wilson, 1989) and the normative Q–Or–Ab triangular plot for granitoids (Section 3.3.2). The TAS diagram for plutonic rocks (Figure 3.2) is useful inasmuch as it is simple and convenient to use. It is important to note, however, that its boundaries are not the same as the boundaries of the TAS diagram for volcanic rocks. There are other classification schemes for plutonic rocks which are based on modal mineralogy, but these are not discussed here.

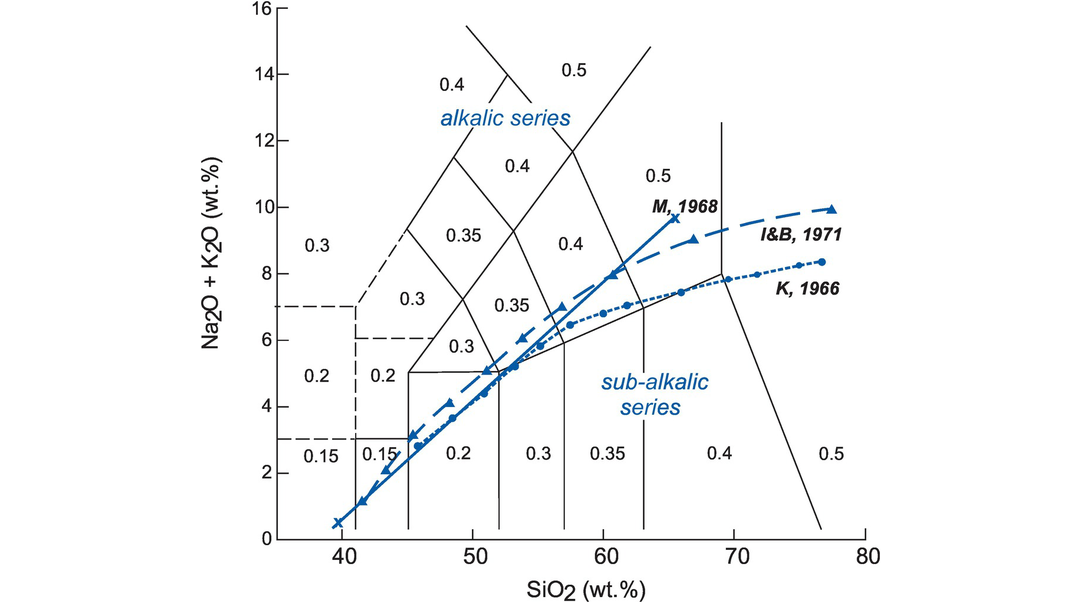

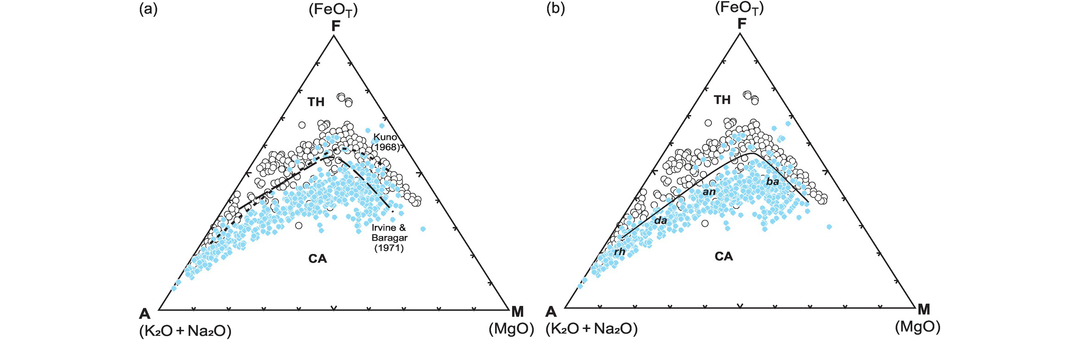

3.2.1.3 Discrimination between the Alkalic and Sub-alkalic Rock Series Using TAS

Igneous rocks can be subdivided into an alkalic or sub-alkalic magma series on the TAS diagram. Using data from Hawaiian basalts, MacDonald and Katsura (1964) were the first to define a boundary separating the alkalic and sub-alkalic (tholeiitic) magma series on a TAS diagram. A later study by MacDonald (1968) expanded the boundary to cover a wider range of SiO2. Similar diagrams by Kuno (1966) and Irvine and Baragar (1971) place the boundary in slightly different positions on the TAS plot (Figure 3.3). Currently, the boundary curve of Irvine and Baragar (1971) is the most widely used, although the recent reassessment by El-Hinnawi (2016a) indicates that the coordinates of MacDonald and Katsura (1964) provide the best distinction between the alkalic and sub-alkalic series for basaltic compositions (SiO2 < 52 wt.%). There is less clarity for compositions with a higher SiO2 content. The boundary coordinates are given in the caption to Figure 3.3.

The TAS diagram for volcanic rocks showing (i) subdivisions between the alkalic and sub-alkalic magma series and (ii) the Fe2O3/FeO ratios for volcanic rock compositions recommended by Middlemost (1989). Note: Boundaries and plotting coordinates (SiO2, total alkalis) are, respectively, from Kuno (1966 – K, 1966 – filled circles [dotted line 45.85, 2.75; 46.85, 3.0; 50.0, 3.9; 50.3, 4.0; 53.1, 5.0; 55.0, 5.8; 55.6, 6.0; 60.0, 6.8; 61.5, 7.0; 65.0, 7.35; 70.0, 7,85; 71.6, 8.0; 75.0, 8.3; 76.4, 8.4]); MacDonald (1968 – M, 1968 – crosses [solid line 39.8, 0.35 to 65.5, 9.7]) and Irvine and Baragar (1971 – I&B, 1971 – filled triangles [dashed line 39.2, 0.0; 40.0, 0.4; 43.2, 2.0; 45.0, 2.8; 48.0, 4.0; 50.0, 4.75; 53.7, 6.0; 55.0, 6.4; 60.0, 8.0; 65.0, 9.6; 66.4, 10.0]). The data are from the compilation of Rickwood (1989). Note the greater divergence between the boundaries at higher SiO2.

Alkaline plutonic rocks enriched in magnesium are known as sanukitoids. They were originally defined by Stern et al. (1989) as plutonic rocks containing 55–60 wt.% SiO2 and with Mg# > 0.6 (see Section 3.3.2). However, it is now known that there are sanukitoid suites which range in composition from pyroxenite to quartz monzonite with SiO2 between 38 wt.% and 68 wt.% and Mg# = 0.49–0.89. This is illustrated in the study by Lobach-Zhuchenko et al. (2008, figure 4).

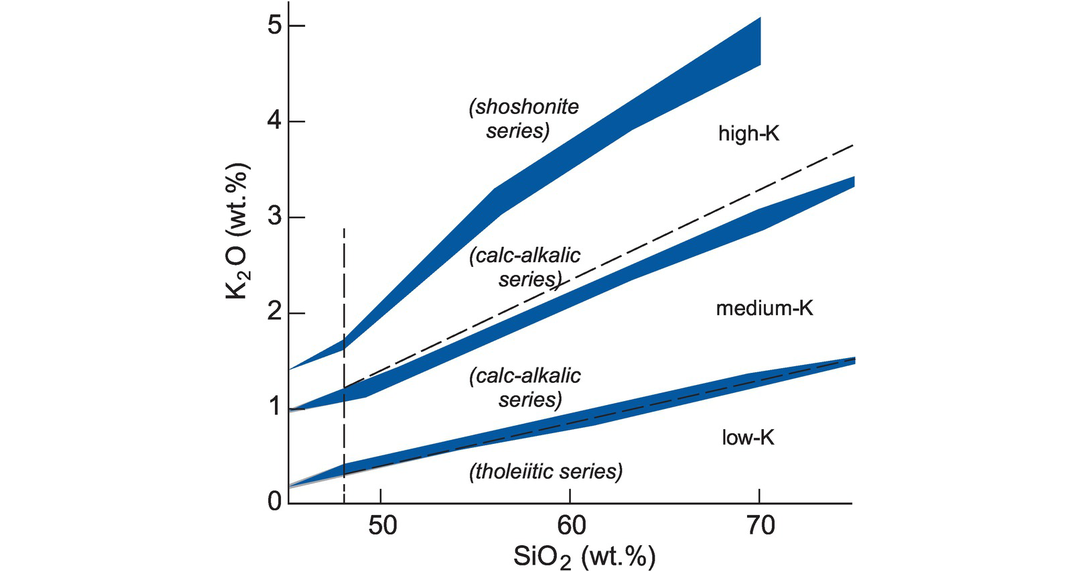

3.2.1.4 The K2O versus SiO2 Diagram for the Sub-division of the Sub-alkalic Series

Volcanic rocks of the sub-alkalic series may be further subdivided into the calc-alkalic or tholeiitic series on the basis of their K2O and SiO2 concentrations (Peccerillo and Taylor, 1976). Le Maitre et al. (1989) proposed a subdivision of sub-alkalic rocks into low-, medium- and high-K types and suggested that these terms be used to qualify the names ‘basalt’, ‘basaltic andesite’, ‘andesite’, ‘dacite’ and ‘rhyolite’. This nomenclature broadly coincides with the low-K (tholeiitic) series, medium-K (calc-alkalic) series and high-K (calc-alkaline) series of Rickwood (1989). A compilation of curves from Rickwood (1989) and Le Maitre et al. (1989) is given in Figure 3.4.

The subdivision of alkalic and sub-alkalic rocks using the K2O versus silica diagram. The diagram shows the subdivisions of Le Maitre et al. (1989) (dashed lines and upper case text) and of Rickwood (1989) (text in parentheses). The shaded regions include the boundaries of Peccerillo and Taylor (1976), Ewart (1982), Innocenti et al. (1982), Carr (1985) and Middlemost (1985) as summarised by Rickwood (1989). The plotting parameters are as follows (SiO2, K2O): Le Maitre et al. (1989): (dashed lines) high-K/medium-K boundary 48.0, 1.2; 68.0, 3.1; medium-K/low-K boundary 48.0, 0.3; 68.0, 1.2; vertical boundary at 48 wt.% SiO2. Rickwood (1989): the band between the shoshonitic series and the high-K series 45.0, 1.38; 48.0, 1.7; 56.0, 3.3; 63.0, 4.2; 70.0, 5.1; and 45.0, 1.37; 48.0, 1.6; 56.0, 2.98; 63.0, 3.87; 70.0, 4.61; the band between the high-K and the calc-alkalic series 45.0, 0.98; 49.0, 1.28; 52.0, 1.5; 63.0, 2.48; 70.0, 3.1; 75.0, 3.43; and 45.0, 0.92; 49.0, 1.1; 52.0, 1.35; 63.0, 2.32; 70.0, 2.86; 75.0, 3.25; the band between the calc-alkalic and the low-K series 45.0, 0.2; 48.0, 0.41; 61.0, 0.97; 70.0, 1.38; 75.0, 1.51; and 45.0, 0.15; 48.0, 0.3; 61.0, 0.8; 70.0, 1.23; 75.0, 1.44.

3.2.2 Classifying Igneous Rocks Using Normative Mineralogy

The norm represents a theoretical mineral assemblage which is calculated from a whole rock chemical analysis. In the context of rock classification it provides the basis for a number of mineralogical classification schemes. The calculated normative mineralogy is based entirely upon the chemistry of the rock and its strength lies in the fact that it permits the classification of rocks, such as glassy rocks, for which the determination of the mode is not possible, and allows a direct comparison to be made between such rocks and their crystalline or metamorphosed counterparts. Hence rocks with the same chemical composition should result in the same normative mineral assemblage, although it is important to note that the norm calculation is sensitive to the oxidation state of iron (see Section 3.2.2.3).

3.2.2.1 CIPW Norm

There are a number of different approaches to calculating the norm but the CIPW norm, named after its originators – Cross, Iddings, Pirrson and Washington (Cross et al., 1902) – is the most commonly used. The CIPW norm calculation makes a number of simplifying assumptions and follows a prescribed set of rules. A simplified version of the calculation scheme is given in Appendix 3.1. An example of the conversion steps needed to calculate molar proportions necessary to determine the norm is given in Table 3.3. Weight percent oxide values (column 1) are divided by their molecular weights (column 2) to calculate molecular proportions (column 3). The molecular proportions are the basis of the norm calculation given in Appendix 3.1. At the end of the calculation the resulting normative minerals are multiplied by their molecular weight to recast them into wt.% (column 9). The CIPW norm calculation can be carried out in Excel using the programme norm 4 (https://minerva.union.edu/hollochk/c_petrology/other_files/norm_calculation.pdf) or in a variety of open-source computer programs such as NORRRAM (González-Guzmán, 2016, in R) or CIPWFULL (Al-Mishwat, 2015, in FORTRAN). However, it is important to understand the principles which lie behind the norm calculation, and so before using these programs we recommend the manual calculation of a simple CIPW norm.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt.% oxide of rock | Mol. wt. | Mol. proportions | Number of cations | Cation proportions | Millications | Cation % | Mole % | Normative minerals | CIPW norm | Cation norm | |

| SiO2 | 61.52 | 60.09 | 1.0238 | 1 | 1.0238 | 1023.80 | 58.03 | 67.86 | Q | 15.94 | 15.12 |

| TiO2 | 0.73 | 79.9 | 0.0091 | 1 | 0.0091 | 9.14 | 0.52 | 0.61 | Or | 12.23 | 12.45 |

| Al2O3 | 16.48 | 101.96 | 0.1616 | 2 | 0.3233 | 323.26 | 18.32 | 10.71 | Ab | 30.71 | 33.2 |

| Fe2O3 | 1.83 | 159.69 | 0.0115 | 2 | 0.0229 | 22.92 | 1.30 | 0.76 | An | 22.52 | 22.98 |

| FeO | 3.82 | 71.85 | 0.0532 | 1 | 0.0532 | 53.17 | 3.01 | 3.52 | Di | 2.17 | 2.18 |

| MnO | 0.08 | 70.94 | 0.0011 | 1 | 0.0011 | 1.13 | 0.06 | 0.07 | Hy | 10.32 | 10.47 |

| MgO | 2.8 | 40.3 | 0.0695 | 1 | 0.0695 | 69.48 | 3.94 | 4.61 | Mt | 2.64 | 1.95 |

| CaO | 5.42 | 56.08 | 0.0966 | 1 | 0.0966 | 96.65 | 5.48 | 6.41 | Il | 1.38 | 1.04 |

| Na2O | 3.63 | 61.98 | 0.0586 | 2 | 0.1171 | 117.13 | 6.64 | 3.88 | Ap | 0.56 | 0.53 |

| K2O | 2.07 | 94.2 | 0.0220 | 2 | 0.0439 | 43.95 | 2.49 | 1.46 | |||

| P2O5 | 0.25 | 141.95 | 0.0018 | 2 | 0.0035 | 3.52 | 0.20 | 0.12 | TOTAL | 98.47 | 99.92 |

| TOTAL | 98.63 | 1.7641 | 100.00 | 100 | An | 34% | 33% | ||||

| Ab | 47% | 48% | |||||||||

| Or | 19% | 18% |

The CIPW norm is widely used in the classification of basalts (Section 3.2.2.4) and in the classification of granitoids (Section 3.2.2.5). Errors can arise in CIPW norm calculations if volatiles in the rock composition are not correctly allocated and if the oxidation state of the iron is incorrectly stated. In addition, some rock types, in particular, cumulate rocks and alkaline rocks with a high CO2 content, may result in the calculation of an improbable range of accessory mineral phases.

3.2.2.2 The Cation Norm

The Barth-Niggli norm, also known as the cation norm or the molecular norm, is an older norm calculation that is no longer widely used. The norm is calculated using the equivalent weights of the oxides, that is, the molecular weight when one cation is present (Barth, 1952). In the case of oxides such as CaO or TiO2 the equivalent weight is the same as the molecular weight, but for Al2O3 or Na2O the equivalent weight is half the molecular weight. The calculation of a cation norm is illustrated in Table 3.3. In this case the wt.% oxide values (column 1) are divided by their equivalent weights (divide by column 2 and multiply by column 4), converted into cation proportions (column 5) and then converted into cation percent (column 7). Molecules are then constructed according to the standard CIPW rules (Appendix 3.1), although the proportions of the components in which cations are allocated are different from the CIPW norm. The cation norm is not recalculated on a wt.% basis, but is expressed in molecular % (column 10). One advantage of the cation norm is that the proportions of opaque minerals are closer to their volume percentages as seen in thin section.

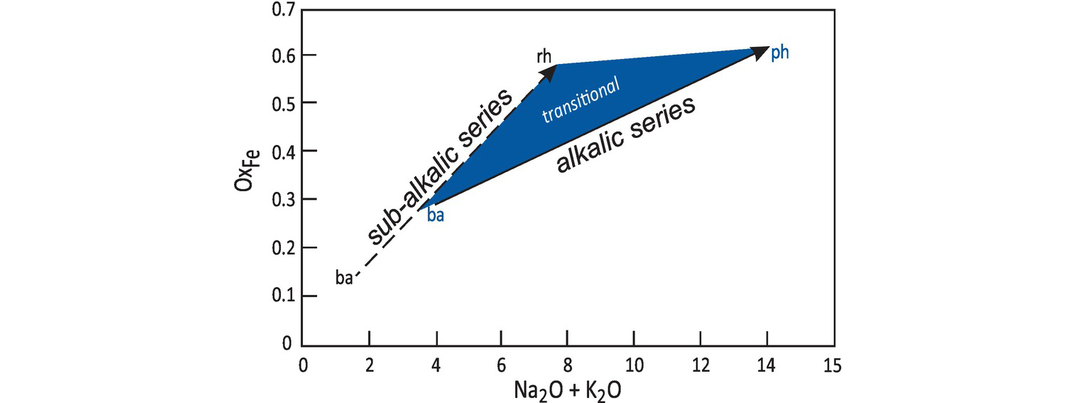

3.2.2.3 Normative Mineralogy and the Oxidation State of Iron

The norm calculation is particularly sensitive to the oxidation state of iron. This is problematic for mafic rocks where the Fe content is typically much higher than in felsic rocks, and can be an issue for felsic rocks since magmatic systems generally become more oxidising as they evolve. Given that Fe is usually reported as either FeO or as Fe2O3 it is necessary to estimate the Fe2O3/FeO ratio in a given rock. Two approaches have been taken. In volcanic rocks, Middlemost (1989) assigned specific values of Fe2O3/FeO to particular rock types in TA-S space (Figure 3.3). El-Hinnawi (2016b), on the other hand, used a database of >12,000 analyses for which Fe was measured as Fe2+ and Fe3+ to directly calculate the Fe2O3/FeO ratio. This study showed that there is a linear relationship between total alkalis (Na2O + K2O) and the degree of iron oxidation (OxFe = Fe2O3/(Fe2O3 + FeO) in wt.%) in the alkalic and sub-alkalic volcanic rock series (Figure 3.5). The equations are:

These results are applicable to the majority of volcanic rock types, although ‘transitional’ basalts with compositions between the two fields are more difficult to constrain.

Average degree of iron oxidation (OxFe = Fe2O3/(Fe2O3 + FeO)) associated with total alkalis of the alkalic and sub-alkalic volcanic rock series (after El-Hinnawi, 2016b). As a magma evolves towards more sialic differentiates, the increase in oxygen fugacity leads to an increase in iron oxidation, resulting in the strong positive correlation for both the alkalic (solid arrow) and sub-alkalic (dashed arrow) series. The arrows indicate direction of evolution from basaltic (ba) to rhyolitic (rh)/phonolitic (ph) compositions. The shaded area indicates region of ‘transitional’ basalts, which will have intermediate OxFe.

Given the widespread use of normative mineralogy in classifying basaltic and granitic rocks and the impact the oxidation state of Fe can have on the normative mineralogy, it is necessary to specify how Fe has been allocated between its two oxidation states when reporting the results of norm calculations.

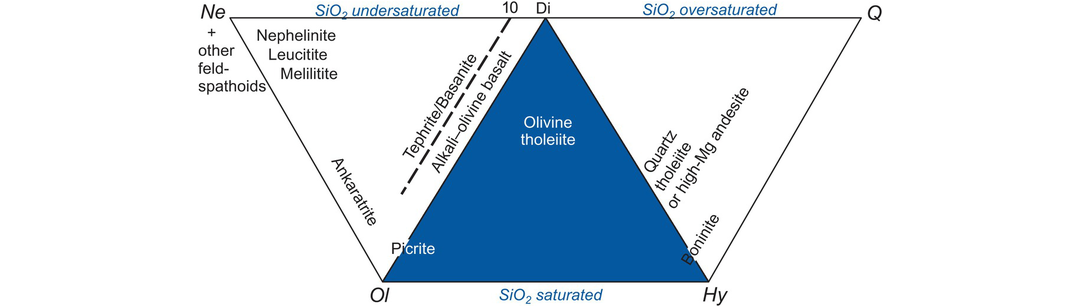

3.2.2.4 Normative Mineralogy and Basalt Classification

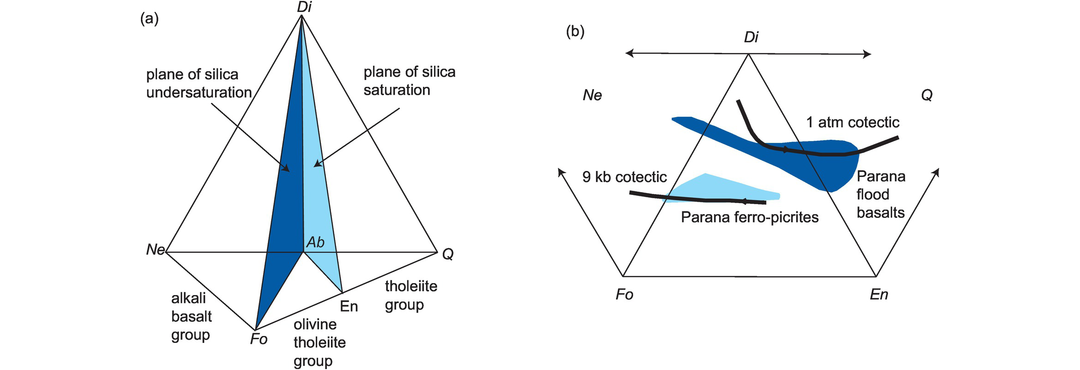

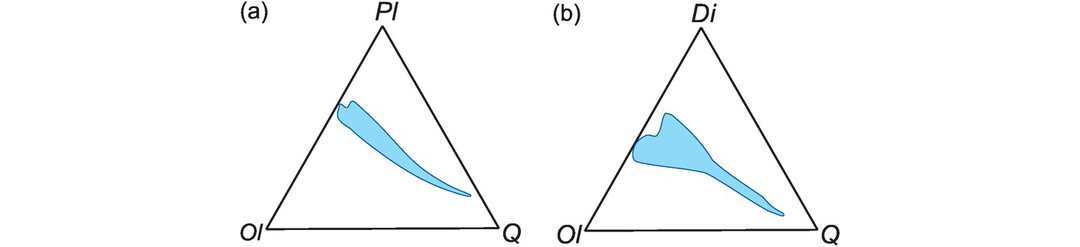

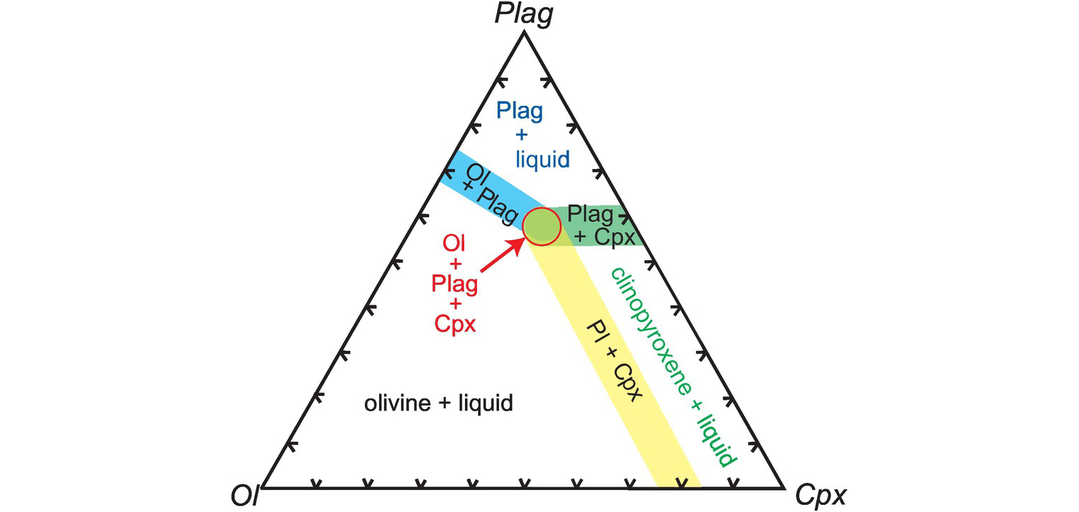

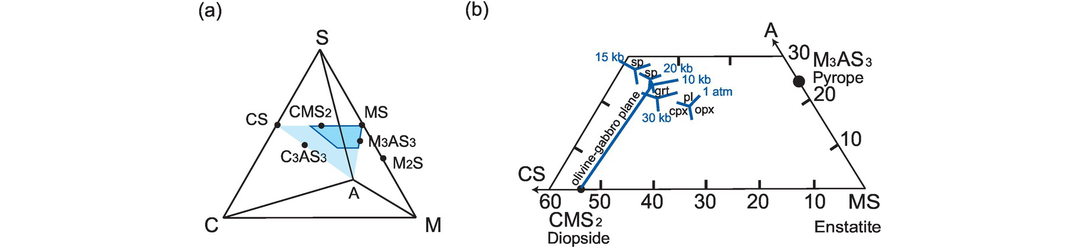

Thompson (1984) proposed a classification scheme for basaltic rocks based upon the CIPW normative proportions of Ne (and other feldspathoids), Ol, Di, Hy and Q (see Appendix 3.1 for abbreviations). This classification diagram (Figure 3.6) is an expanded version of the Yoder-Tilley (1962) low-pressure basalt tetrahedron (Figure 3.22a). The three equilateral triangles of the diagram Ne–Ol–Di, Ol–Di–Hy and Di–Hy–Q represent basaltic and related rocks which are, respectively, undersaturated, saturated and oversaturated with silica (Figure 3.6). Thus silica undersaturated basalts (alkali basalts) are characterised by normative Ol and Ne, silica saturated basalts (olivine tholeiites) are characterised by normative Hy and Ol, and silica oversaturated basalts (quartz tholeiites) are characterised by normative Q and Hy.

The classification of basalts and related rocks based upon their CIPW normative compositions expressed as Ne–Ol–Di, Ol–Di–Hy or Di–Hy–Q.

Silica saturation is particularly important in basaltic magmas, because in dry magmas this single parameter determines the crystallisation sequence of minerals and evolution of the melt during fractional crystallisation. Weight % normative compositions (calculated assuming FeO/(FeO + Fe2O3) = 0.85, or Fe2O3/FeO = 0.18) are projected onto one of the three triangles by summing the three relevant normative parameters and calculating the value of each as a percentage of their sum. The calculation and plotting procedure for triangular diagrams is given in Section 3.3.3. This diagram is intended to be used with basalts which have MgO > 6 wt.% and should not be used for highly evolved magmas. Disadvantages of this classification are that it uses only about half of the calculated norm and so is not fully representative of the rock chemistry. It is also sensitive to small errors in Na2O and so is inappropriate for altered rocks.

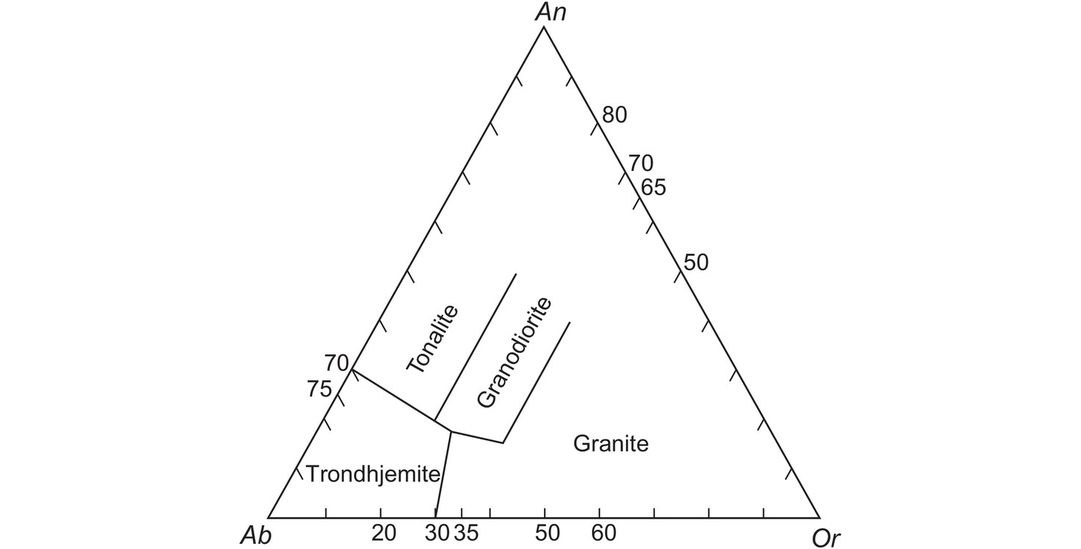

3.2.2.5 Normative Mineralogy and Granite Classification

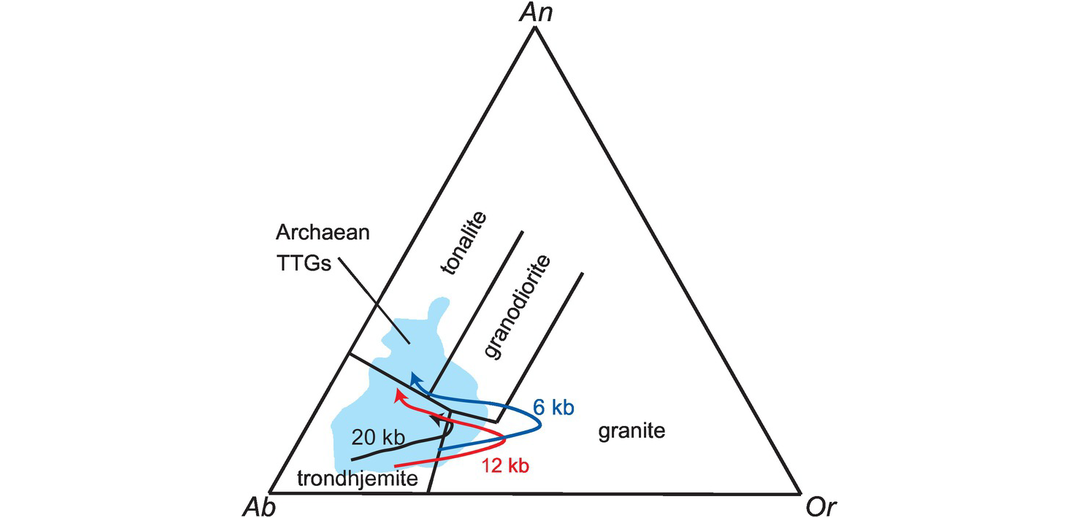

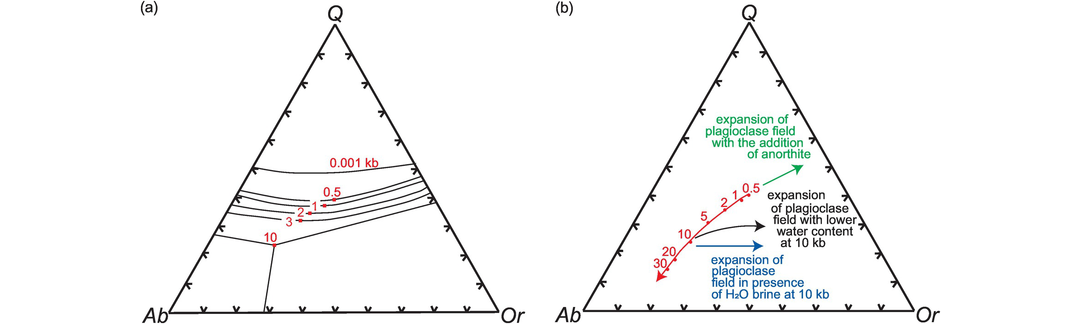

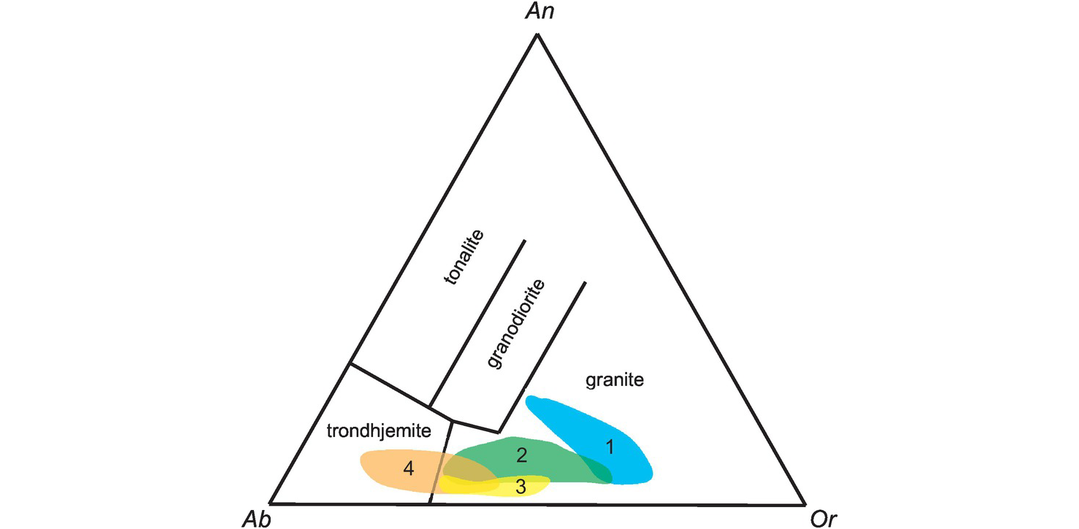

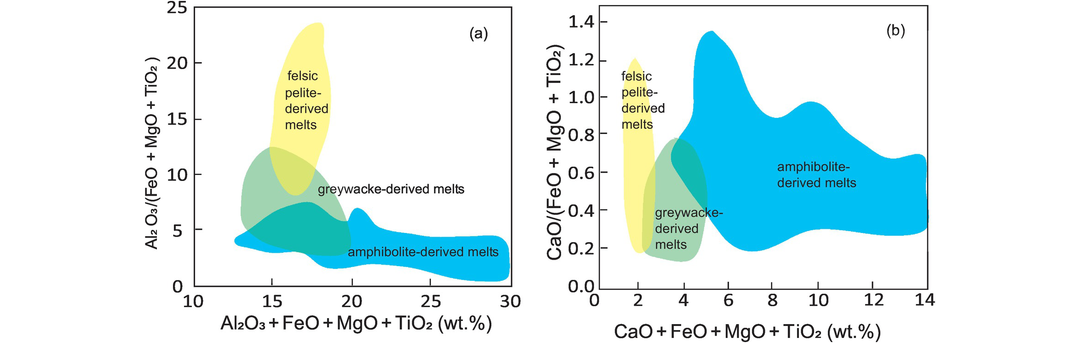

The Ab–An–Or normative classification diagram of Barker (1979) modified from O’Connor (1965) provides a convenient way of classifying felsic plutonic rocks on the basis of their major element chemistry (Figure 3.7). The normative calculation provides a more accurate estimate of feldspar compositions than a modal classification, for it reflects solid solution in the feldspars. The An–Ab–Or diagram represents a projection from quartz onto the feldspar face of the normative ‘granite’ tetrahedron Q–Ab–An–Or. The diagram can be applied to felsic rocks with more than 10% normative quartz and is based entirely upon the normative feldspar composition recast to 100%. The feldspar compositions in this classification were originally calculated using the Barth-Niggli molecular norm, although it is not clear whether this procedure has been followed by all users. That said, the plotting parameters in the Ab–An–Or projection are within 2% of each other from either norm calculation scheme; this is illustrated in Table 3.3 where the Ab–An–Or plotting parameters for a tonalite are calculated using both the CIPW and the molecular norm. Field boundaries of the original O’Connor (1965) diagram were empirically defined from a dataset of 125 plutonic rocks for which there was both normative and modal data. Barker’s (1979) revised classification has the advantage of field boundaries which are clear and easy to reproduce, and which effectively separate tonalites, trondhjemites, granites and granodiorites from each other. The diagram can also be used (with caution) for deformed and metamorphosed granitic rocks, permitting an estimate of their original magma type.

The classification of ‘granitic’ rocks according to their molecular normative An–Ab–Or composition after Barker (1979).

3.2.3 Classifying Igneous Rocks Using Cations

The conversion of wt.% oxides to cations is calculated in the same way as in the initial stages of the cation norm calculation. The wt.% of the oxide is divided by the equivalent weight of the oxide set to one cation. It is sometimes alternatively expressed as the wt.% oxide divided by the molecular weight of the oxide and multiplied by the number of cations in the formula unit. Thus the wt.% SiO2 is divided by 60.09. However, the wt.% Al2O3 is divided by 101.96 and then multiplied by 2. If millications are needed, then multiply the cationic proportions by 1000. Worked examples are given in columns 5 and 6 of Table 3.3.

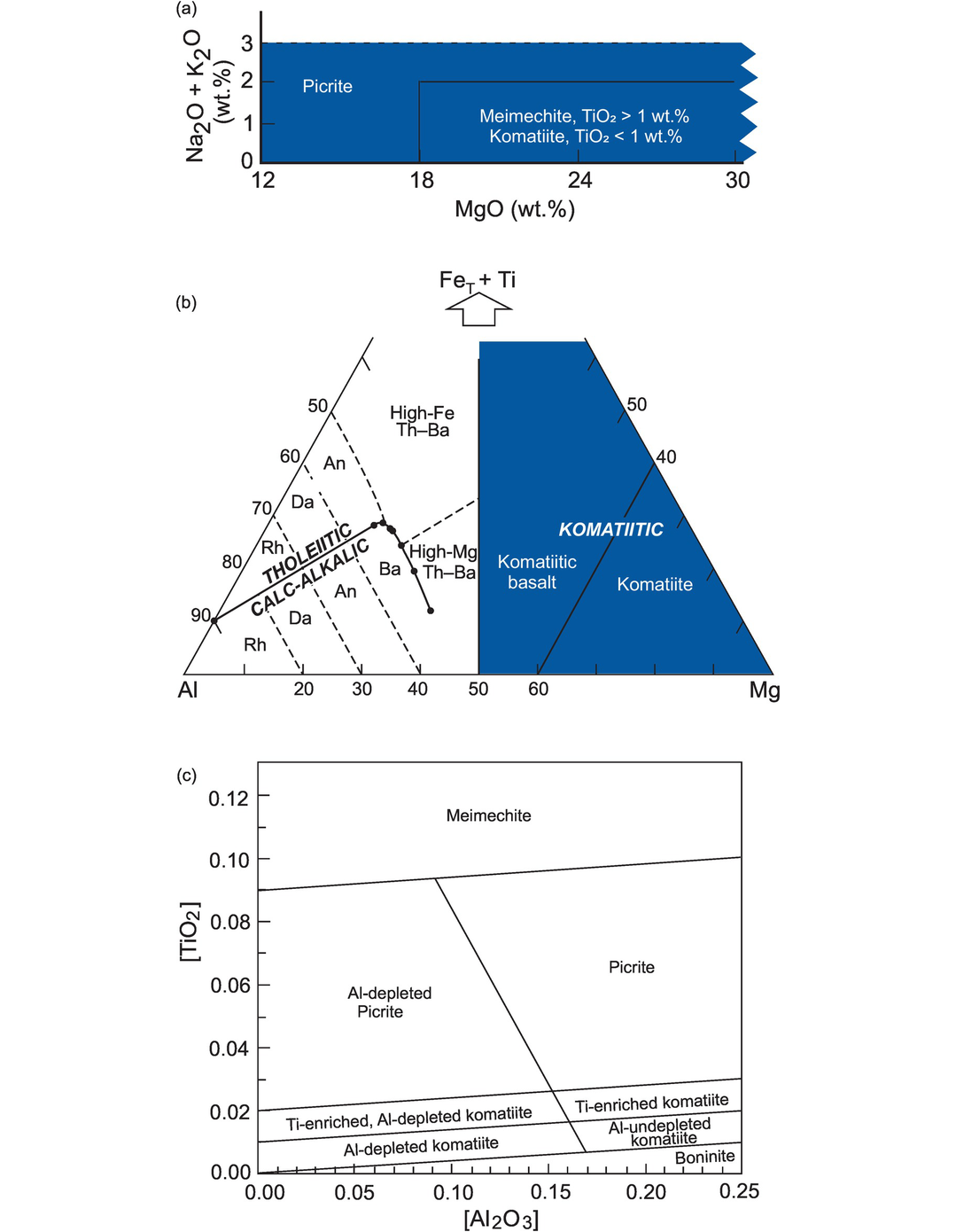

3.2.3.1 The Jensen Plot

Jensen (1976) proposed a cation-based classification scheme for sub-alkalic volcanic rocks. It is based upon the cation proportions of Σ(Fe2+ + Fe3+ + Ti), Al and Mg recalculated to 100% and plotted on a triangular diagram (Figure 3.8b). The elements were selected on the basis of their variability in sub-alkalic rocks, for the way in which they vary in inverse proportion to each other and for their stability under low grades of metamorphism. Thus, this classification scheme can be used successfully with metamorphosed volcanic rocks that have experienced mild metasomatic loss of alkalis – an advantage over other classification schemes for volcanic rocks. However, this diagram is important because it shows komatiites and komatiitic basalts as separate fields from those of basalts and calc-alkaline rocks and so is useful for Archean metavolcanic rocks. The original diagram of Jensen (1976) was slightly modified by Jensen and Pyke (1982), who moved the komatiitic basalt/komatiite field boundary to a lower value of Mg, and this is the version presented in Figure 3.8b. The plotting parameters of the field boundaries are taken from Rickwood (1989).

The classification of high-Mg volcanic rocks. (a) High-Mg rocks (shaded region in lower left of the TAS diagram in Figure 3.1) are further divided on the basis of their wt.% MgO and TiO2 (Le Maitre et al., 2002). (b) High-Mg basalts and komatiitic rocks are classified using cation percentages of Al, (Fe[total] + Ti) and Mg. The field boundaries are after Jensen (1976) and Jensen and Pyke (1982) (heavy lines). An, andesite; Ba, basalt; Da, dacite, Rh, rhyolite; Th, tholeiite. The boundary between the tholeiitic and calc-alkalic fields is defined by the coordinates (Al, Fe + Ti, Mg) 90, 10, 0; 53.5, 28.5, 18; 52.5, 29, 18.5; 51.5, 29, 19.5; 50.5, 27.5, 22; 50.3, 25, 24.7; 50.8, 20, 29.2; 51.5, 12.5, 36 (Rickwood, 1989; corrected). (c) High-Mg rocks classified using molecular proportions of Al2O3 and TiO2 normalised to unity using the equation [Al2O3] = Al2O3/(2/3 – MgO – FeO) and [TiO2] = (TiO2/(2/3 – MgO – FeO). (Hanski et al., 2001)

3.2.3.2 The Hanski Plot

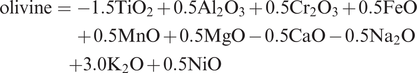

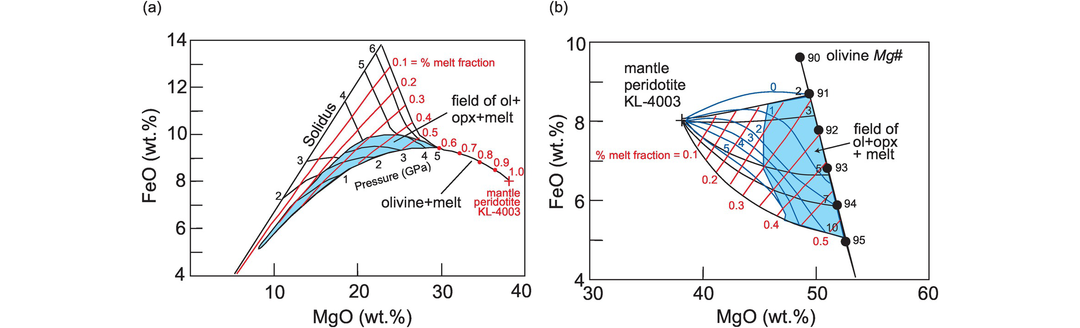

The Hanski plot is also useful for distinguishing between high-Mg rocks (Figure 3.8c). The diagram is based upon the molecular proportions of Al2O3 and TiO2 (normalised to unity) and projected from olivine. All the iron is assumed to be ferrous (Hanski et al., 2001). The plotting parameters are as follows:

Figure 3.8c distinguishes between komatiites and picrites and between Al- and Ti-enriched/depleted komatiites. It has the advantage that rock or liquid compositions with an olivine-controlled liquid-line-of-descent will have constant [Al2O3] and [TiO2] values, thus a fixed position on the plot. However, the diagram does not distinguish between komatiites and komatiitic basalts.

3.2.3.3 Classification of High-Mg Rocks on the TAS Diagram

Although not a cation plot, it is relevant here to consider the classification of high-Mg rocks within the framework of the TAS diagram. Le Maitre et al. (2002) sought to differentiate between picrites and komatiites and other highly magnesian rocks on the basis of their MgO and TiO2 content (see the shaded region in Figures 3.1 and 3.8a).

3.2.4 A Combined Major Element Oxide and Cation Classification for Granitoids

We recommend a major element scheme for distinguishing between groups of granitoids. We suggest that this is superior to trace element classifications since these can be distorted by the accumulation of accessory mineral phases (Bea, 1996). The scheme proposed here is non-genetic and so lacks any assumption about the origin of the granitoid, thereby avoiding some of the pitfalls of the SIAM-type granite classification of Chappell and White (1974). Further it avoids the less-intuitive approach of the R1-R2 classification proposed by de la Roche et al. (1980).

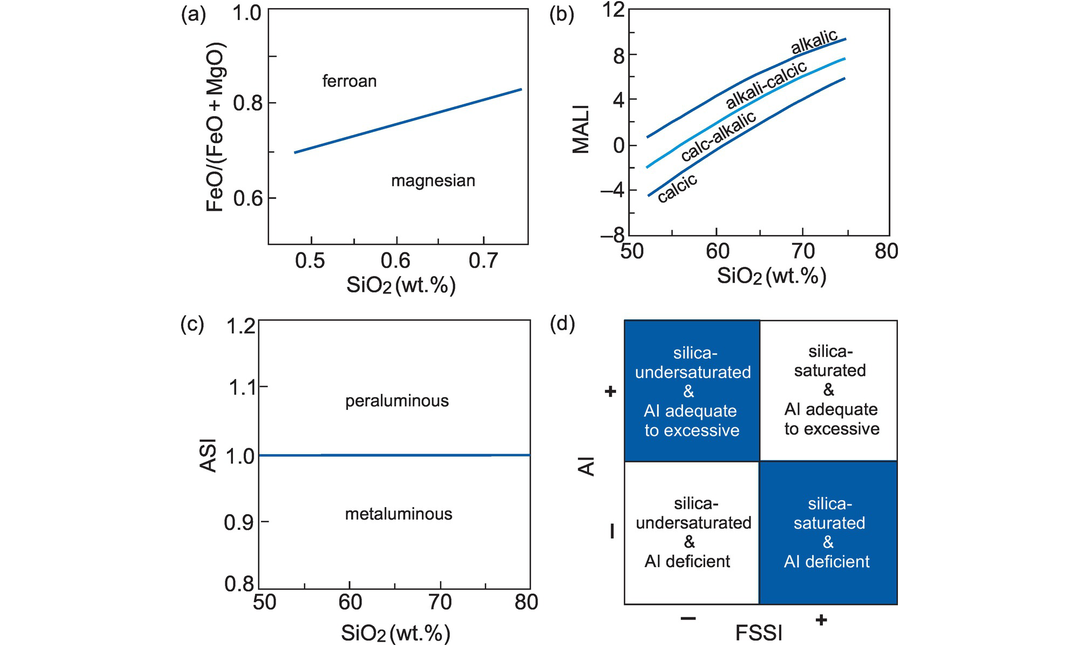

Instead, we follow the classification scheme of Frost et al. (2001), modified by Frost and Frost (2008). The ‘Frost’ classification subdivides granitoids on the basis of five indices:

1. an iron index

2. a modified alkali-lime index (after Peacock, 1934)

5. a feldspathoid saturation index.

These parameters are summarised in Table 3.4, plotted in Figure 3.9 and discussed in more detail below.

Granite classification using major elements (after Frost et al., 2001 and Frost and Frost, 2008). (a) The Fe-index distinguishes magnesian versus ferroan rocks on the basis of total iron in the rock calculated as wt.% Fe-index = FeO + 0.9Fe2O3/(FeO + 0.9Fe2O3 + MgO). This is similar to the ‘calc-alkalic’ and ‘tholeiitic’ trends of Miyashiro (1974). The boundary fits the equation FeO* = 0.46 + 0.005SiO2. (b) The modified alkali-lime index (MALI) reflects the wt.% relationship of Na2O + K2O – CaO relative to SiO2 and is a function of the crystallising assemblage. This index separates the alkalic, alkali-calcic, calc-alkalic and calcic rocks from one another. (c) The alumina saturation index (ASI) is based on molecular Al/(Ca – 1.67P + Na + K) and defines rocks as metaluminous (ASI < 1) or peraluminous (ASI > 1). (d) The combination of the molecular alkalinity index (AI) and the normative feldspathoid silica-saturation index (FSSI) identifies alkalic rocks, and SiO2-saturated or under-saturated rocks, respectively. AI = molecular Al/(Ca – 1.67P + Na + K) (after Shand, 1947); FSSI = normative Q − [Lc + 2(Ne + Kp)]/100.

| Index | Formula | Units | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fe-index | FeO/(FeO+MgO) | Wt.% oxide | ||

| 2. Modified alkali-lime index (MALI) | Na2O + K2O – CaO | Wt.% oxide | ||

| 3. Aluminum-saturation Index (ASI) | Al/(Ca − 1.67P + Na + K) | Molecular | ||

| 4. Alkalinity index (AI) | Al − (K + Na) | Molecular | ||

| 5. Feldspathoid silica-saturation Index (FSSI) | Q − [Lc − 2(Ne + Kp)]/100 | Molecular norm | ||

The Fe-index separates those rocks enriched in Fe from those that are not and identifies them as ferroan or magnesian (Figure 3.9a). The index is calculated as FeO* = [FeO + 0.9 Fe2O3/(FeO + 0.9 Fe2O3 + MgO)] (wt.%) and the boundary between ferroan and magnesian rocks fits the equation [FeO* = 0.46 + 0.005 SiO2] (Frost and Frost, 2008).

The modified alkali-lime index (MALI) reflects the wt.% abundance of sodium and potassium relative to calcium using the equation Na2O + K2O - CaO. When the MALI index is plotted against SiO2 it distinguishes between alkalic, alkali-calcic, calc-alkalic and calcic compositions (Figure 3.9b). Rocks with more than ~ 60% SiO2 are controlled by the abundance and composition of feldspars and quartz; at lower SiO2, the removal of augite during fractionation exerts a dominant control on increasing MALI in the residual magma.

The aluminium saturation index (ASI) is based on molecular Al/(Ca - 1.67P + Na + K) and identifies rocks as metaluminous or peraluminous (after Shand, 1947; Zen, 1988) (Figure 3.9c). Peraluminous varieties (ASI > 1) have more Al than is needed to make feldspars (molecular Na + K < AI), whereas metaluminous varieties (ASI < 1) lack the necessary Al needed to make feldspars (molecular Na + K > AI). Alkaline rocks are deficient in either alumina or silica or both, and contain higher alkalis than can be accommodated in feldspar alone.

The alkalinity index (AI) and the feldspathoid silica-saturation index (FSSI) combine to discriminate between alkaline rocks on the basis of alumina relative to alkalis [AI = molecular Al - (K + Na)] as well as between silica-saturated and undersaturated compositions (Figure 3.9d). The FSSI is based on the molecular norm using the equation Q - [Lc + 2(Ne + Kp)]/100.

On the basis of these five indices, it is possible to classify the majority of granitoids.

3.2.5 The Chemical Classification of Sedimentary Rocks

Most sedimentary rock classification schemes use those features that can be observed in hand specimen or thin section. In clastic rocks these are grain size and the mineralogy of the grains and matrix (Milliken, 2014; Garzanti, 2019) and in limestones they are depositional textures (Dunham, 1962) or grain compositions (Folk, 1959).

The chemical composition of clastic rocks is a complex function of the composition of the protolith, mediated by the processes of weathering, transport, diagenesis and depositional environment. For this reason the bulk-rock chemistry of a clastic sediment is more useful in investigating processes such as hydraulic sorting, chemical weathering and the detrital mineralogy of the source than in rock classification (Johnsson, 1993; Mangold et al., 2011; Fedo et al., 2015). Nevertheless, there are now abundant, precise elemental data for both coarse- and fine-grained sedimentary rocks, and so, with the above caveats in mind, some applications associated with major element chemistry are presented below.

3.2.5.1 Sandstones

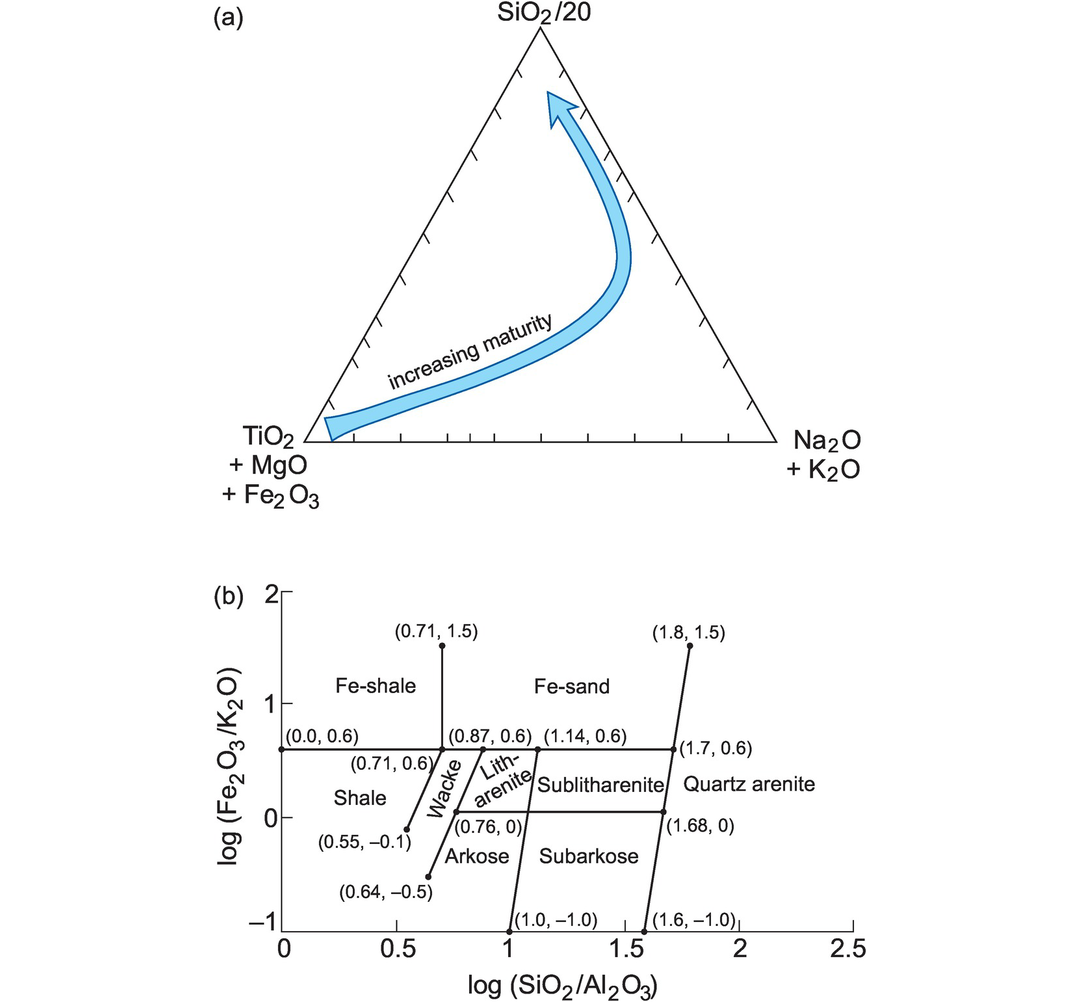

Sandstone geochemistry can be used to distinguish between mature and immature varieties using the relative abundances of quartz, feldspar + clay, and ferromagnesian minerals. Prolonged weathering breaks down ferromagnesian minerals and so depletes the sediment in Ti + Mg + Fe. In a similar way through the breakdown of feldspars and micas the sediment is depleted in K + Na. This gives rise to an increase in residual quartz (SiO2) and a high level of compositional maturity as illustrated in Figure 3.10a (Roser et al. 1996). Using these same principles for the classification of sandstones and shales, Herron (1988) plotted the parameters log (SiO2/Al2O3) against log(Fe2O3T/K2O) (Figure 3.10b). The ratio Fe2O3T/ K2O is a measure of the stability of ferromagnesian minerals and permits sandstones to be more successfully classified than simply using the K-Na scheme of Pettijohn et al. (1972). Shales are identified on the basis of their low SiO2/Al2O3. A further advantage of the Herron classification is that it can be used to identify shales, sandstones, arkoses and carbonate rocks in situ from geochemical well logs using neutron activation and gamma-ray tools (Herron and Herron, 1990). However, sediment classification diagrams based on major elements must be applied with caution as Na and K can be easily mobilised during diagenesis and metamorphism. The degree of chemical alteration can be evaluated using the alteration parameters listed in Table 3.5 and is discussed further in Section 3.3.

Major element classification of sediments. (a) Sandstone maturity as a function of wt.% SiO2/20, K2O + Na2O, and TiO2 + MgO + Fe2O3 (after Kroonenberg, 1990). The mature sandstones are nearest the SiO2 apex. (b) Terrigenous sandstones and shales in a log (Fe2O3/K2O) versus log (SiO2/Al2O3) plot (after Herron, 1988). The numbers shown in parentheses are the plotting coordinates for the field boundaries expressed as [log (SiO2/Al2O3), log (Fe2O3/K2O)].

| Index | Units | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Index of compositional variability (ICV) | ||

| [Fe2O3 + K2O + Na2O + CaO + MgO + MnO + TiO2]/Al2O3 | Wt.% oxide | Cox et al. (1995) |

| Plagioclase index of alteration (PIA) | ||

| [(Al2O3 - K2O)/(Al2O3 + CaO + Na2O - K2O)] × 100 | Wt.% oxide | Fedo et al. (1995) |

| Chemical index of weathering (CIW) | ||

| [Al2O3/(Al2O3 + CaO + Na2O)] × 100 | Wt.% oxide | Harnois (1988) |

| Chemical index of weathering without CaO (CIW′) | ||

| Al2O3/(Al2O3 + Na2O) | Wt.% oxide | Cullers (2000) |

| Chemical index of alteration (CIA) | ||

| [Al2O3/(Al2O3 + CaO* + Na2O + K2O)] × 100 | Molar | Nesbitt and Young (1982) |

| Chemical proxy of alteration (CPA) | ||

| 100 × [Al2O3/(Al2O3 + Na2O)] | Molecular norm | Buggle et al. (2011) |

3.2.5.2 Mudrocks

There is no widely recognised major element chemical classification of mudrocks. This is surprising given that they have a more variable chemistry than sandstones. Whole-rock major element data are typically presented normalized to a reference composition such as the Post-Archean Australian Shale (PAAS) of Taylor and McLennan (1985). The index of compositional variability (ICV) ([Fe2O3 + K2O + Na2O + CaO + MgO + MnO + TiO2]/Al2O3) has also been used to indicate increasing or decreasing proportions of clay minerals on the basis that clay minerals have greater amounts of alumina (Cox et al., 1995). More recently Fazio et al. (2019) used Na2O versus SiO2 and Na2O versus Al2O3 (wt.%) to distinguish between varieties of mudrock.

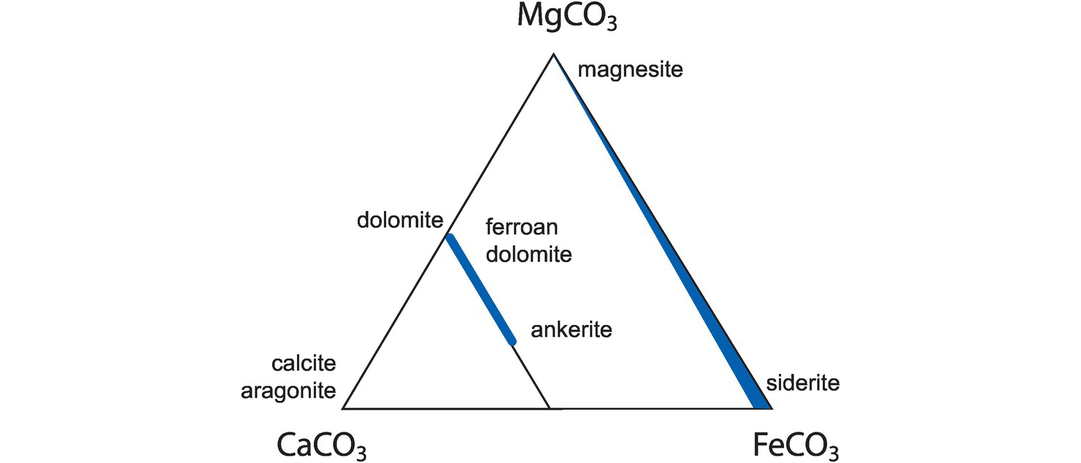

3.2.5.3 Limestones

Most carbonate rocks are dominated by calcite, dolomite and their ferroan equivalents and contain only a limited amount of other constituents. Consequently, their major element chemistry is dominated by Ca, Mg and Fe (Figure 3.11). Limestones and marbles can be classified on the basis of their relative CaCO3 and MgCO3 content and divided into two main categories: magnesite (≥50% MgCO3) and calcite-dolomite [CaCO3–(Ca, Mg)CO3]. The calcite-dolomite group can be further subdivided into six categories on the basis of their purity (Carr and Rooney, 1983).

Carbonate rock classification. Carbonate minerals stable at sub-greenschist (<250°C ) conditions (data from Anovitz and Essene, 1987). Ca, Mg and Fe provide the dominant major element components. Shaded areas signify solid-solution.

Future developments in this field include the use of chemostratigraphy on carbonate cores using a hand-held XRF. Yarbrough et al. (2019) used major element analyses to better characterise the Upper Jurassic reservoir facies of the carbonate Smackover Formation, Alabama, and found that the elements Al, Si, Ca, Ti and Fe were significant (>95% confidence level) predictors of porosity.

3.2.6 Discussion

It can be seen from the above that there is no simple major element chemical classification scheme for all igneous rocks or for all sediments. The most effective classification is for fresh volcanic igneous rocks using the TAS diagram. Plutonic rocks are more complicated, although for granitic rocks the normative An-Or-Ab diagram is a good place to start, followed by the use of major element oxide diagrams (Section 3.2.4) to recognize distinct chemical groups of granitoids. There is no simple, uniformly applicable classification scheme for sedimentary rocks based on their major element compositions, although in the future a more complex statistical evaluation of major element compositions using multivariate analysis is likely to provide better insight to sediment genesis (Mongelli et al., 2006; Hofer et al., 2013).

3.3 Variation Diagrams

A table of geochemical data from a particular igneous province, metamorphic terrain or sedimentary succession may at first sight show an almost incomprehensible variation in the concentration of individual elements. Given that the samples are likely to be geologically related, a major task for the geochemist is to devise a way in which the variation between individual rocks may be simplified and condensed so that relationships between the individual samples may be identified. The device which is most commonly used and has proved invaluable in the examination of geochemical data is the variation diagram. This is a bivariate graph on which two selected variables are plotted. Diagrams of this type were popularised as long ago as 1909 by Alfred Harker in his Natural History of Igneous Rocks, and one particular type of variation diagram, in which SiO2 is plotted along the x-axis, is known as the Harker diagram.

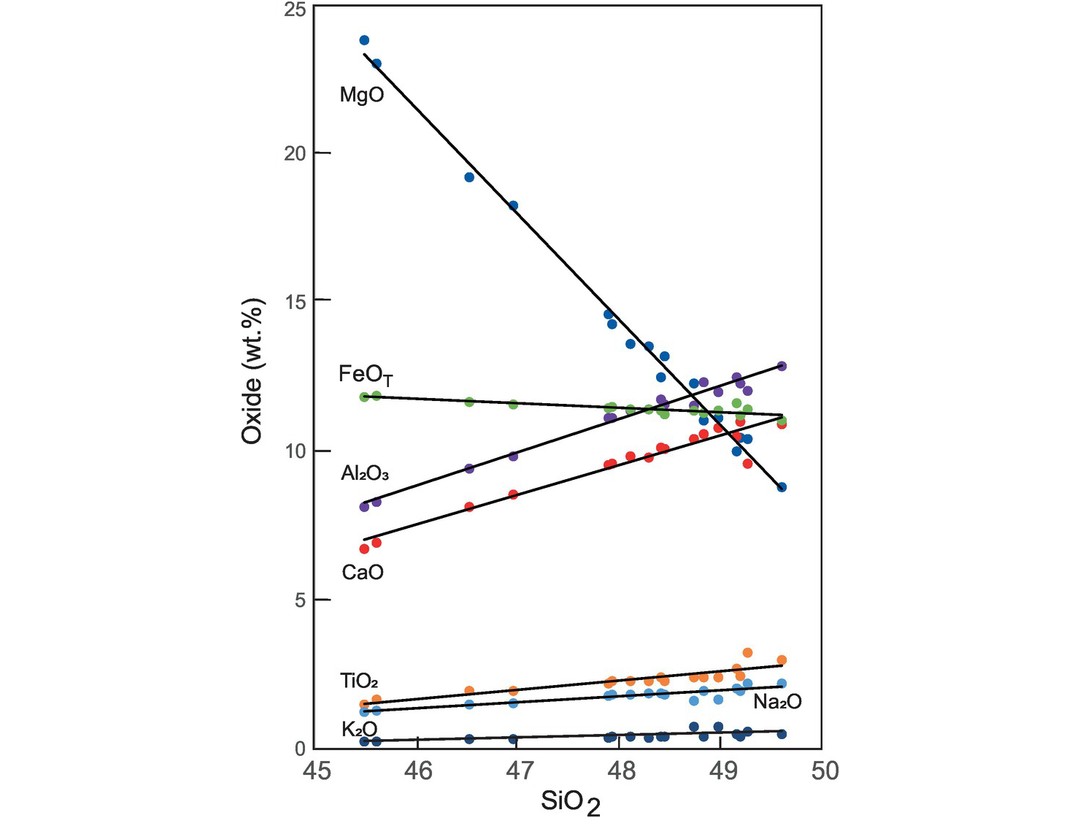

An illustration of the usefulness of variation diagrams can be seen from a comparison of the data in Table 3.6 and the variation diagrams plotted for the same data (Figure 3.12). It is clear that the variation diagrams have condensed and rationalised a large amount of numerical information and show qualitatively that there is an excellent correlation (either positive or negative) between each of the major elements displayed and SiO2. Traditionally, this strong geochemical coherence between the major elements in a related suite of rock, in this case basalts from a single volcano, has been used to suggest that there is an underlying process which can explain the relationships between the major elements. Nonetheless, from the discussion in Chapter 2 on closure and the problems associated with applying univariate statistics to multivariate data, caution is needed, and such correlations should always be rigorously tested.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 48.29 | 48.83 | 45.61 | 45.50 | 49.27 | 46.53 | 48.12 | 47.93 | 46.96 | 49.16 | 48.41 | 47.90 | 48.45 | 48.98 | 48.74 | 49.61 | 49.20 |

| TiO2 | 2.33 | 2.47 | 1.70 | 1.54 | 3.30 | 1.99 | 2.34 | 2.32 | 2.01 | 2.73 | 2.47 | 2.24 | 2.35 | 2.48 | 2.44 | 3.03 | 2.50 |

| Al2O3 | 11.48 | 12.38 | 8.33 | 8.17 | 12.10 | 9.49 | 11.43 | 11.18 | 9.90 | 12.54 | 11.80 | 11.17 | 11.64 | 12.05 | 11.60 | 12.91 | 12.32 |

| Fe2O3 | 1.59 | 2.15 | 2.12 | 1.60 | 1.77 | 2.16 | 2.26 | 2.46 | 2.13 | 1.83 | 2.81 | 2.41 | 1.04 | 1.39 | 1.38 | 1.60 | 1.26 |

| FeO | 10.03 | 9.41 | 10.02 | 10.44 | 9.89 | 9.79 | 9.46 | 9.36 | 9.72 | 10.02 | 8.91 | 9.36 | 10.37 | 10.17 | 10.18 | 9.68 | 10.13 |

| MnO | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| MgO | 13.58 | 11.08 | 23.06 | 23.87 | 10.46 | 19.28 | 13.65 | 14.33 | 18.31 | 10.05 | 12.52 | 14.64 | 13.23 | 11.18 | 12.35 | 8.84 | 10.51 |

| CaO | 9.85 | 10.64 | 6.98 | 6.79 | 9.65 | 8.18 | 9.87 | 9.64 | 8.58 | 10.55 | 10.18 | 9.58 | 10.13 | 10.83 | 10.45 | 10.96 | 11.05 |

| Na2O | 1.90 | 2.02 | 1.33 | 1.28 | 2.25 | 1.54 | 1.89 | 1.86 | 1.58 | 2.09 | 1.93 | 1.82 | 1.89 | 1.73 | 1.67 | 2.24 | 2.02 |

| K2O | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.48 |

| P2O5 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.23 |

| H2O+ | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| H2O− | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| CO2 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| TOTAL | 100.01 | 99.89 | 99.84 | 99.86 | 99.84 | 99.93 | 100.00 | 99.99 | 99.93 | 100.05 | 100.02 | 99.95 | 100.05 | 100.06 | 100.07 | 99.90 | 99.95 |

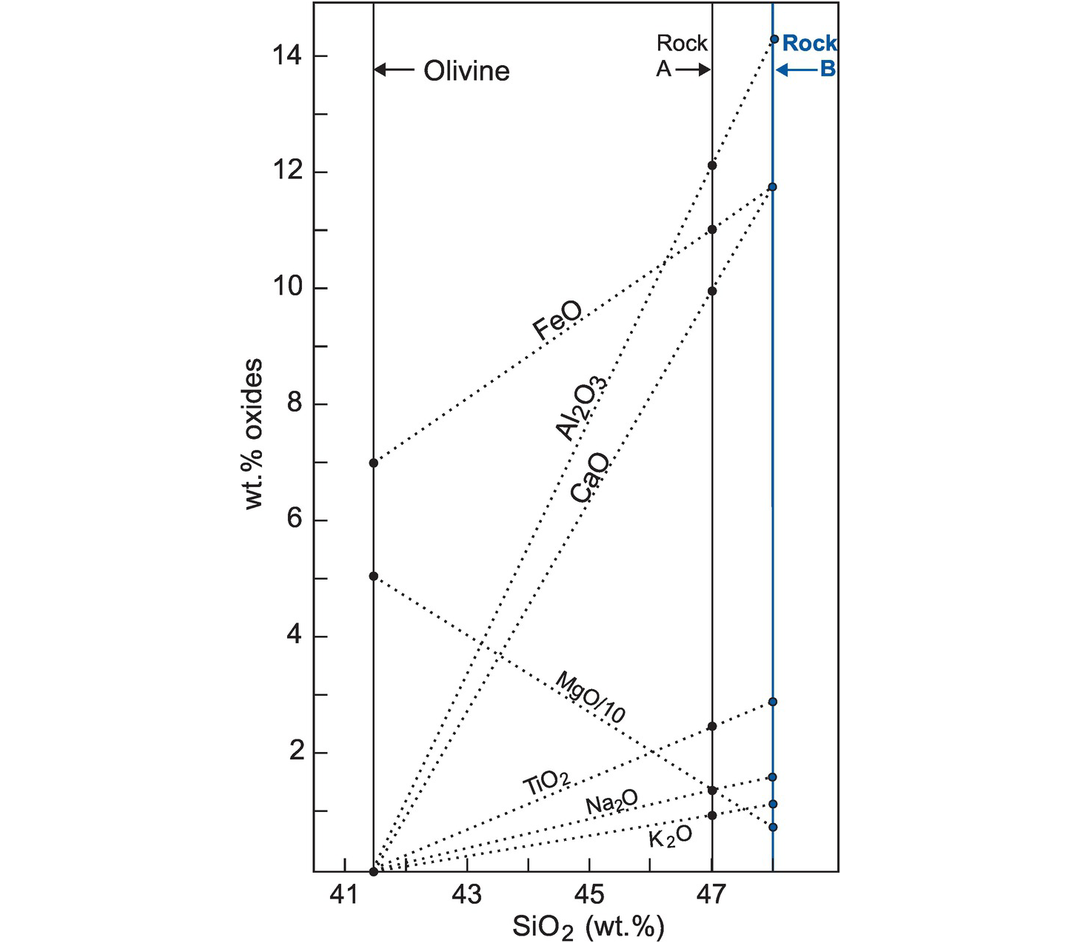

Bivariate plots of major element oxides versus SiO2. The data represent basaltic lavas from the lava lake Kīlauea Iki associated with the 1959–1960 volcanic eruption of Kīlauea, Hawai‘i (from Richter and Moore, 1966). A linear trend is fitted for each of the oxides. The data are given in Table 3.6.

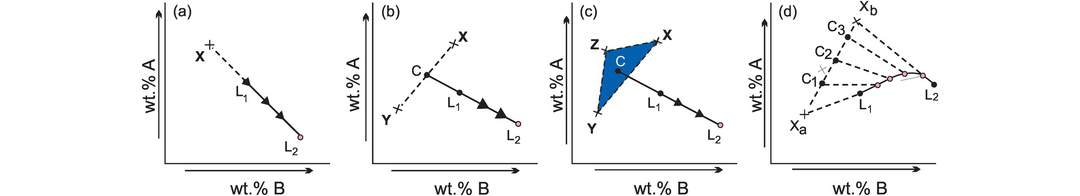

3.3.1 Recognising Geochemical Processes on a Major Element Variation Diagram

Most trends on variation diagrams are the result of mixing. In igneous rocks the mixing may be between two magmas, because of the addition and/or subtraction of solid phases during contamination or fractional crystallisation, or due to the addition of melt increments during partial melting. In sedimentary rocks trends on a variation diagram will also result from mixing, but in this case it is the mixing of chemically distinct components that defines the composition of the sediment. In metamorphic rocks trends on a variation diagram will usually reflect the processes in the igneous or sedimentary protolith, masked to some degree by specific metamorphic processes such as metasomatism, the chemical alteration of a rock by non-deuteric fluids. In some instances, however, deformation can mechanically mix more than one rock type, giving rise to a mixing line of metamorphic origin. Below we consider some of the more important mixing processes.

3.3.1.1 Fractional Crystallisation

Fractional crystallisation is a major process in the evolution of many igneous rocks and is frequently the cause of trends seen on their variation diagrams. The fractionating mineral assemblage is normally indicated by the phenocrysts present. A test of crystal fractionation may be made by accurately determining the composition of the phenocrysts using an electron microprobe and then plotting the compositions on the same graph as the rock analyses. If trends on a variation diagram are controlled by phenocryst compositions, it may be possible to infer that the rock chemistry is controlled by crystal fractionation. It should be noted, however, that (1) fractional crystallisation may take place at depth in which case the fractionating phases may not be represented in the lower pressure and temperature phenocryst assemblage and, as discussed below, that (2) mineralogical control can also be exercised by partial melting processes.

The importance of fractional crystallisation was expounded at length by Bowen (1928) in his book The Evolution of the Igneous Rocks and who argued that geochemical trends for volcanic rocks represent a ‘liquid line of descent’. This is the path taken by residual liquids as they evolve through the differential withdrawal of minerals from the magma. The ideas of Bowen now need to be qualified in the context of modern findings in the following ways:

1. Trends identical to those produced by crystal fractionation can also be produced by partial melting.

2. Only phenocryst-poor or aphyric volcanic rocks will give a true indication of the liquid path.

3. Rarely does a suite of volcanic rocks showing a progressive chemical change erupt in a time sequence. Even a highly correlated trend on a variation diagram of phenocryst-free volcanic rocks from a single volcano is unlikely to represent a liquid line of descent. Rather, it represents an approximation of the liquid line of descent of similar, overlapping, sub-parallel lines of descent.

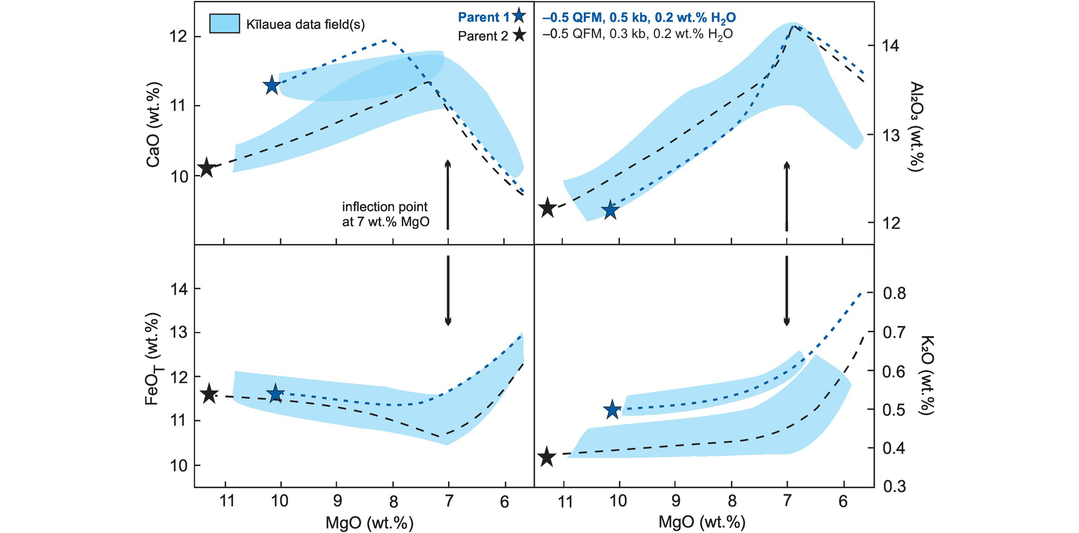

As an example, the variation in composition of olivine-rich basalts from the lava lake Kīlauea Iki, Hawai‘i (Table 3.6), are presented as bivariate plots (Figure 3.12). This variation is thought to be the product of fractional crystallisation which was ‘controlled principally by the physical addition or removal of olivine phenocrysts’ (Richter and Moore, 1966). A detailed comparison with olivine compositions indicates that other phases were also involved in crystal fractionation but that olivine was the major control.

3.3.1.2 Assimilation and Fractional Crystallisation

If phenocryst compositions cannot explain trends in a rock series and a fractional crystallisation model does not appear to work, it is instructive to consider the possibility of simultaneous processes such as assimilation of the country rock combined with fractional crystallisation. Assimilation plus fractional crystallisation, often abbreviated AFC, was first proposed by Bowen (1928), who argued that the latent heat of crystallisation during fractional crystallisation can provide sufficient thermal energy to consume the wall rock. Consequently, hot magmas undergoing fractional crystallisation assimilate cool crust as a consequence of heat transfer from the magma to the crust.

Kuritani et al. (2005) illustrate this process for an alkali basalt-dacite suite from the magma chamber of the Rishiri volcano in northern Japan. They show that major element variations in the lava suite can be explained by mixing of a magma in the main magma body with a melt transported from a mushy boundary layer in the partially fused floor of the magma chamber. A slightly different example comes from mantle petrology where very high temperature melts have the capacity to react with the rock through which they are transiting, in particular, when the two are out of equilibrium. A well-studied example is the reaction between MORB melts and highly depleted harzburgitic mantle. This reaction consumes orthopyroxene and precipitates olivine, leading to dunite channels in the harzburgite which indicate the route followed by the migrating melt (e.g., Kelemen, 1990 and Kelemen et al., 1995).

It has been proposed that AFC processes can result in the ‘decoupling’ of the major element chemistry from that of the trace elements and/or isotopes and so may not always be evident in the major element data. For example, the contamination of a basalt precipitating olivine, clinopyroxene and plagioclase will result in increased precipitation of the fractionating minerals but may cause only a minor change in the silica content of the liquid. Trace element levels and isotope ratios, however, might be changed and provide a better means of recognising assimilation.

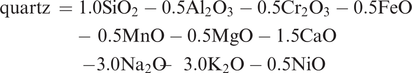

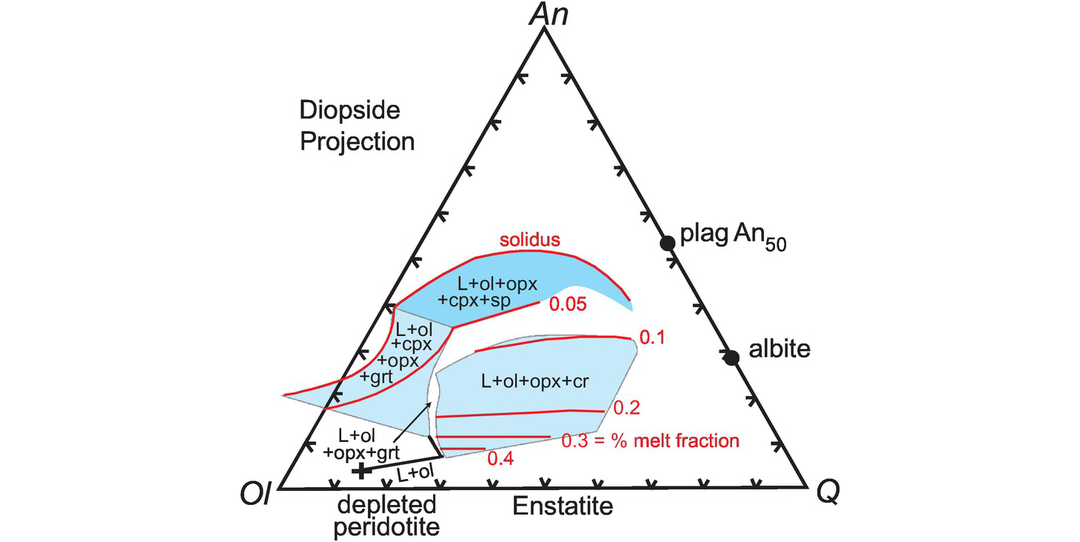

3.3.1.3 Partial Melting

Progressive fractional melting will show a trend on a variation diagram which is controlled by the chemistry of the solid phases being added to the melt. However, this can be very difficult to distinguish from a fractional crystallisation trend on a major element variation diagram, for both processes represent crystal–liquid equilibria involving almost identical liquids and identical minerals. One way in which progressive partial melting and fractional crystallisation may be distinguished using major elements is if the two processes take place under different physical conditions. For example, if partial melting takes place at great depth in the mantle and fractional crystallisation is a crustal phenomenon, then some of the phases involved in partial melting will be different from those involved in fractional crystallisation. Trace elements (discussed in Chapter 4) provide additional means of discriminating between these two processes.

3.3.1.4 Mixing Lines in Sedimentary Rocks

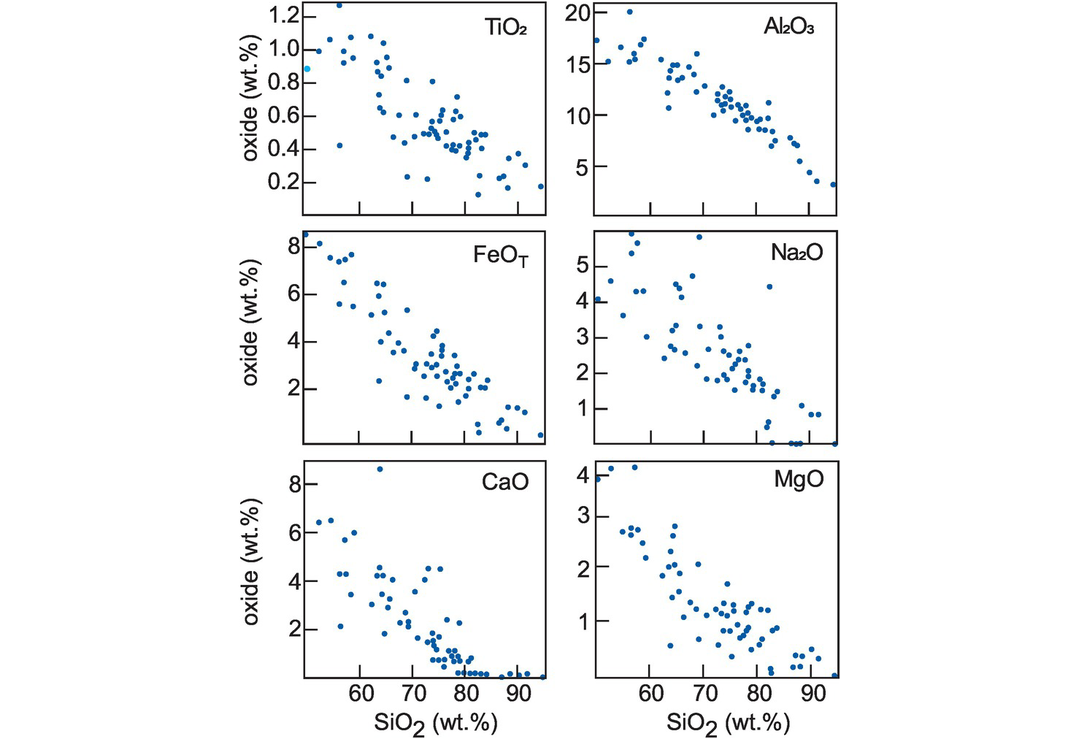

Trends on variation diagrams for sedimentary rocks may result from the mixing of the different components which constitute the sediment. There are a number of examples of this effect in the literature. Bhatia (1983) in a study of turbidite sandstones from eastern Australia presented bivariate plots (Figure 3.13) in which there is a change in the mineralogical maturity, as evidenced by an increase in quartz (SiO2) coupled with a decrease in the proportions of lithic fragments and feldspar represented by the other oxides.

Bivariate plots for quartz-rich sandstone suites from eastern Australia (after Bhatia, 1983). The increase in SiO2 reflects an increased mineralogical maturity, that is, a greater quartz content and a smaller proportion of other detrital minerals.

3.3.1.5 The Identification of Former Weathering Conditions in Sedimentary Rocks

A good measure of the degree of chemical weathering can be obtained from the chemical index of alteration (CIA; Nesbitt and Young, 1982):

Concentrations are expressed as molar values and CaO* is CaO in silicate phases only. The index was originally devised to reconstruct palaeoclimatic conditions from early Proterozoic sediments in northern Canada but has subsequently been used as a proxy to quantify the intensity of chemical weathering in drainage basins (Shao et al., 2012).

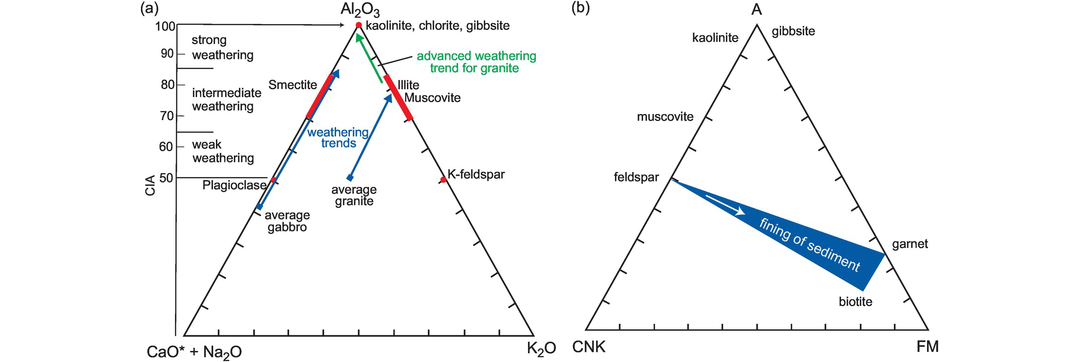

An extension of the CIA index is the (CaO* + Na2O)–Al2O3–K2O triangular plot (Nesbitt and Young (1984, 1989). On a diagram of this type the initial stages of weathering form a trend parallel to the tie between (CaO* + Na2O) and Al2O3 of the diagram, whereas advanced weathering shows a marked loss in K2O as compositions move towards the Al2O3 apex (Figure 3.14a). The trends follow mixing lines representing the removal of alkalis and in solution the breakdown of first plagioclase and then potassium feldspar and finally the ferromagnesian silicates. Deviations from such trends can be used to infer chemical changes resulting from diagenesis or metasomatism (Nesbitt and Young, 1984, 1989). This approach has also been applied to mudstones, and the major and trace element chemistry of ancient and modern muds can be used to determine the degree of weathering in their source (Nesbitt et al., 1990).

Weathering effects. (a) The (CaO + Na2O)–Al2O3–K2O diagram showing weathering intensity and the weathering trends for an average granite and an average gabbro (after Nesbitt and Young, 1984, 1989; Shao et al., 2012). The advanced weathering trend for granite is also shown. Compositions are plotted as molar proportions. CaO* represents the CaO associated with the silicate fraction of the sample. (b) The A (Al2O3), CNK (CaO + Na2O + K2O), FM (FeOT + MgO) molar proportions diagram showing chemical change with sediment grain size.

Nesbitt and Young (1996) also proposed an A–CNK–FM diagram which uses the molar proportions of Al2O3–(CaO + Na2O + K2O)–(FeOT + MgO) to show those chemical changes in sediments which are a function of grain size. It also demonstrates an increase in the ferromagnesian component with decreasing grain size (Figure 3.14b).

3.3.1.6 Artificial Trends

Sometimes trends on variation diagrams are artificially produced by the numerical processes used in plotting the data rather than reflecting geochemical relationships. This is well documented by Chayes (1960) and Aitchison (1986), who have shown that correlations in compositional data can be forced as a result of the unit sum constraint (see Section 2.2). The most helpful way to circumvent this problem is to examine trends on variation diagrams in the light of a specific hypothesis to be tested. The closeness of fit between the model and the data can then be used to evaluate the hypothesis.

3.3.2 Selecting a Variation Diagram

Two main types of variation diagrams – bivariate plots and ternary diagrams – are widely used by geochemists and are considered here.

3.3.2.1 Bivariate Plots

The principal aim of a bivariate plot, such as that illustrated in Figure 3.12, is to show variation between samples and to identify trends. Hence the element plotted along the x-axis of the diagram should be selected either to show the maximum variability between samples or to illustrate a particular geochemical process. Normally, the oxide which shows the greatest range in the dataset would be selected – in many cases this would be SiO2, but with basic igneous rocks it could be MgO and in clay-bearing sediments Al2O3. The initial stage of a geochemical investigation often requires the preparation of a large number of diagrams in order to delimit the possible geological processes operating. In such cases the initial screening of the data is best done using a correlation matrix (see Section 2.4.5) to explore for strong correlations. However, it is important to remember that meaningless correlations can arise through a cluster of data points and a single outlier. Similarly, poor correlations can arise if the dataset contains multiple populations, each with a different trend. More normally, and more fruitfully, most geochemical investigations are designed to solve a specific problem and to test a particular hypothesis – usually formulated from geological or other geochemical data. In this case the plotting parameter for a variation diagram should be selected with the process to be tested in mind. For example, in the case of an igneous rock suite for which a crystal fractionation mechanism is envisaged, then an element should be selected which is contained in the fractionating phase and that will be enriched or depleted in the melt.

(a) Bivariate plots using SiO2 as the x-axis. These are the oldest form of variation diagram and are one of the most frequently used means of displaying major element data (see Figures 3.12 and 3.13). SiO2 is commonly chosen as the plotting parameter for many igneous rock series and for suites of sedimentary rocks with a variable quartz content because it is the major constituent of the rock and shows greater variability than any of the other oxides. However, the very fact that SiO2 is the most abundant oxide can sometimes lead to spurious correlations, as discussed in Section 3.3.2.2.

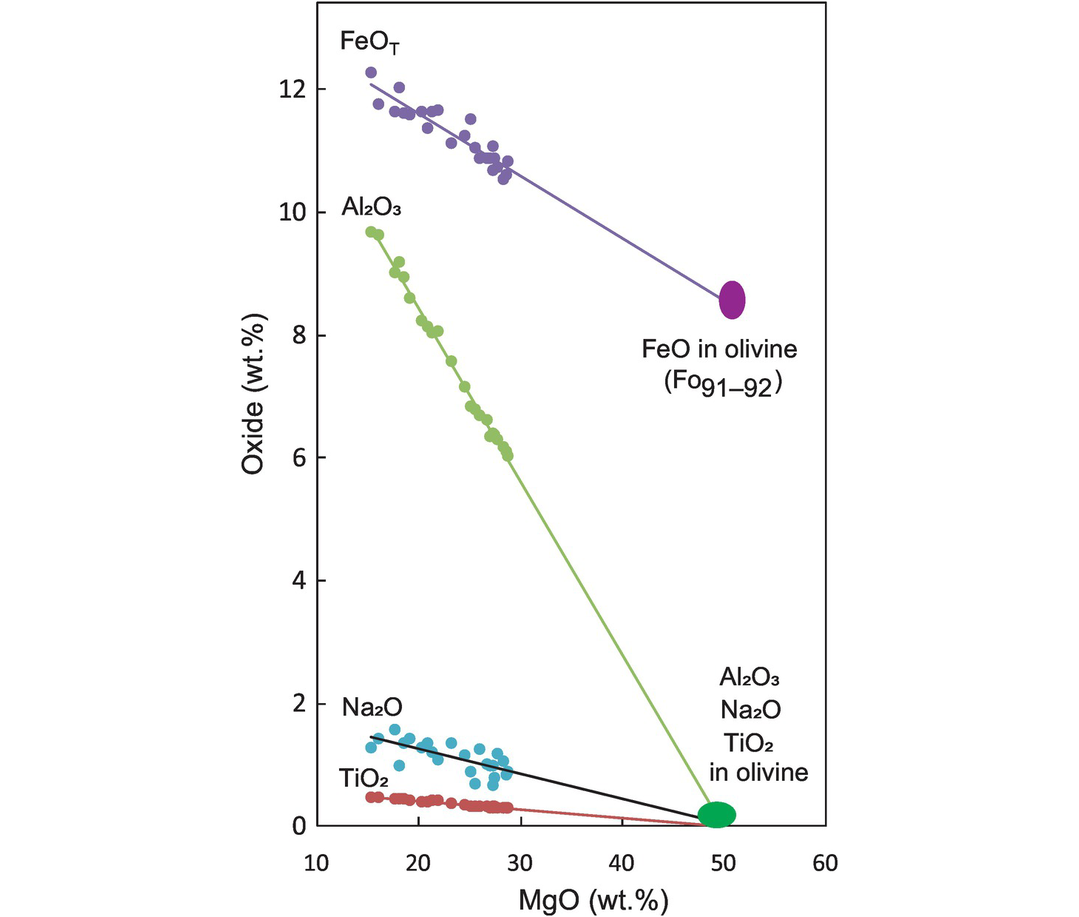

(b) Bivariate plots which use MgO as the x-axis. Another common bivariate diagram uses MgO on the x-axis instead of SiO2. This is most appropriate for mafic and ultramafic suites in which the range of SiO2 concentration may be small. MgO, on the other hand, is an important component of the solid phases in equilibrium with mafic melts, such as olivine and the pyroxenes, and shows a great deal of variation due either to the breakdown of magnesian phases during partial melting or to their removal during fractional crystallisation. Figure 3.15 shows an olivine-controlled fractionation trend in komatiites from the Belingwe greenstone belt in Zimbabwe (data from Bickle et al., 1993). Mg# (for definition, see subsection (e) below) is sometimes substituted for MgO, but the underlying principle is the same – to use the component with the greatest spread.

(c) Bivariate plots using cations. It is sometimes simpler to display mineral compositions on a variation diagram if major element chemical data are plotted as cation %, that is, the wt.% oxide value divided by the molecular weight and multiplied by the number of cations in the oxide formula and then recast to 100% (see Section 3.2.2 and Table 3.3). Alternatively, the results may be expressed as mol %, that is, the wt.% oxide values divided by the molecular weight and recast to 100% (see Section 3.2.2 and Table 3.3).

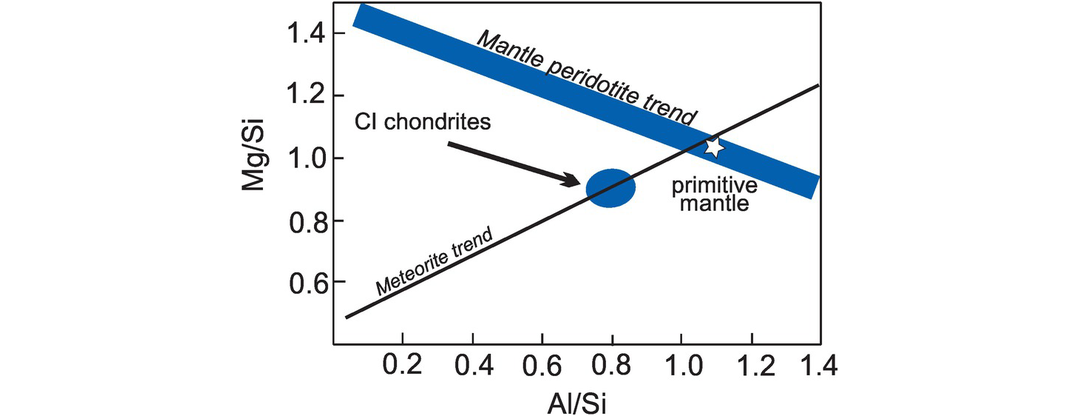

(d) Elemental weight ratio plots. The Al/Si versus Mg/Si diagram is used to show differences in the composition of meteoritic materials and identify the processes operating during the differentiation of the Earth’s mantle. These elements are chosen because they represent the more refractory elements formed during the condensation of the solar nebula, and the ratio plot represents the relative fractionation of the different planetary materials. The plotting parameters are calculated by reducing the oxide wt.% of each of the components to their elemental wt.% concentrations; that is, multiply Al2O3 by 0.529, SiO2 by 0.467, and MgO by 0.603. In Figure 3.16 trends for mantle peridotites and meteorites are plotted together with the field for the likely chondritic material parental to the Earth and the primitive mantle compositions from Table 3.2.

(e) Bivariate plots using the magnesium number (Mg#). The older geochemical literature carries a large number of examples of complex, multi-element plotting parameters which were used as a measure of fractionation during the evolution of an igneous sequence. These are rather complicated to use and difficult to interpret, and have fallen into disuse. One which is usefuland so survives, however, is based on the magnesium–iron ratio, the so-called magnesium number. The magnesium–iron ratio is particularly useful as an index of crystal fractionation in basaltic liquids for here the Mg-Fe ratio changes markedly in the early stages of crystallisation as a result of the higher Mg-Fe ratio of the liquidus ferromagnesian minerals than that of their host melts. The Mg# has been variously defined as follows: MgO/(MgO + FeO + Fe2O3), 100 Mg/(Mg + Fe2+), (Mg/Mg + Fetot), and presented either by weight or atomic proportions. We define the Mg# as 100 × Mg2+/(Mg2+ + Fe2+tot) calculated in atomic proportions. To calculate the Mg# divide the wt.% oxide values for MgO and FeOT (recalculated as Fe2+) by their respective molecular weights of 40.3 and 71.8. Whenever the term Mg# is used, the formula used should be specified.

Oxides versus MgO variation for komatiites from the Archaean Belingwe greenstone belt in Zimbabwe (data from Bickle et al., 1993). The extended lines show that the fractionation trend is principally controlled by olivine with the composition Fo91–92. The slight scatter in the Na2O trend probably indicates a small amount of element mobility.

Differentiation of planetary materials. Elemental Al/Si versus Mg/Si plot showing the meteorite and peridotitic mantle trends relative to CI chondrites and the composition of the Earth’s primitive mantle.

3.3.2.2 Compositional Data and Bivariate Diagrams

Statisticians have been warning geochemists about their inappropriate treatment of compositional data for several decades (Section 2.2.2.1). This criticism is typified in the comment on bivariate diagrams by Aitchison and Egozcue (2005), who state that Harker diagrams are ‘best condemned as misleading and best left out of any attempts to interpret compositional variability’. A similar sentiment is put more mildly by Buccianti and Grunsky (2014): ‘Compositional data analysis in geochemistry: Are we sure to see what really occurs during natural processes?’ This ongoing challenge to the time-honoured treatment of compositional data, and in particular, its representation on bivariate plots, presents the geochemical community with a dilemma, but experience seems to suggest that the challenge from the statistical community is misplaced for several reasons:

1. Bivariate diagrams seem to work and yield geologically meaningful results.

2. There is little evidence from the application of the log-ratio approach, the recommended alternative (Section 2.7.1), that this methodology provides a deeper or superior understanding of geochemical and petrological processes as displayed in bivariate plots. This may in part reflect its dominant application to the compositional analysis of soils, volcanic gases and water chemistry (see Buccianti et al., 2006), rather than the geochemical data associated with geochemistry and petrology.

3.3.2.3 So Why Do Bivariate Plots Appear to Work?

An essential element missing from the debate between statisticians and geochemists over the use and misuse of bivariate diagrams is an appreciation of the geological context. When a suite of samples is collected to test a particular hypothesis or to investigate a particular process, the data are set in a particular context which in turn places constraints on the interpretation of the data. In other words – and this is a theme which will recur throughout this text – geological field control is essential for the meaningful interpretation of geochemical data.

Cortés (2009) takes issue with the criticism of bivariate diagrams by Aitchison and Egozcue (2005) and argues that bivariate diagrams ‘are not a correlation tool but [rather] a graphical representation of the mass actions and mass balances in the context of a geological system’. They serve as a simple display of evolutionary trends which are thought to represent a process or set of processes; the trends observed, ‘spurious or not, are given by the law of mass action’. Hence the expectation is not to discover the covariance structure associated with these trends, but rather to interpret them within a geological context, and where trends are observed these may be used as robust evidence of the link between samples. He further argues that trends on bivariate diagrams can be used quantitatively to calculate the proportion of species involved in a particular geological process. For example, he suggests that a suite of basalts from a particular lava flow might be collected because they are expected to be chemically related. If, in addition, there is field evidence to suggest that these basalts have experienced a common process such as olivine fractionation, then there is a testable hypothesis as to the nature of their relationship. Thus, Cortés (2009), following Rollinson (1992), cites the major element oxide data for samples from the Kīlauea Iki lava lake (Table 3.6, Figure 3.12) which show near perfect, but allegedly spurious, correlations. In line with the geological context, however, the trends confirm a common magmatic origin – the working hypothesis behind the data collection. Further, in the context of mass balance, the variation between samples can be shown to be consistent with olivine addition and removal, again the working hypothesis set by the geological context.

We support the logic of Cortés (2009) and argue that given a geological context, bivariate plots can be an important exploratory tool for the visualisation of geochemical data, a point which is also acknowledged by Egozcue (2009) in his response to Cortés’s (2009) critique. Thus, a suite of bivariate plots for a single dataset remains a powerful tool for understanding geological processes. This conclusion is entirely consistent with the view of log-ratios expressed by Rock (1989). Geochemists work with rock compositions in which, for the most part, variation is controlled by minerals with fixed stoichiometries and together these data must be interpreted within the geological context in which the samples were found.

The preceding discussion argues that compositional data analysis may tell us that the correlation coefficient computed for a particular trend is not meaningful and that the correlation is spurious; nevertheless, the trend may be real and have geological meaning. In the case of bivariate major element plots, it is not the value of the correlation coefficient that is important; rather, it is the presence and shape (linear, curvilinear or kinked) of the trends that are significant. These are the properties that need to be interpreted.

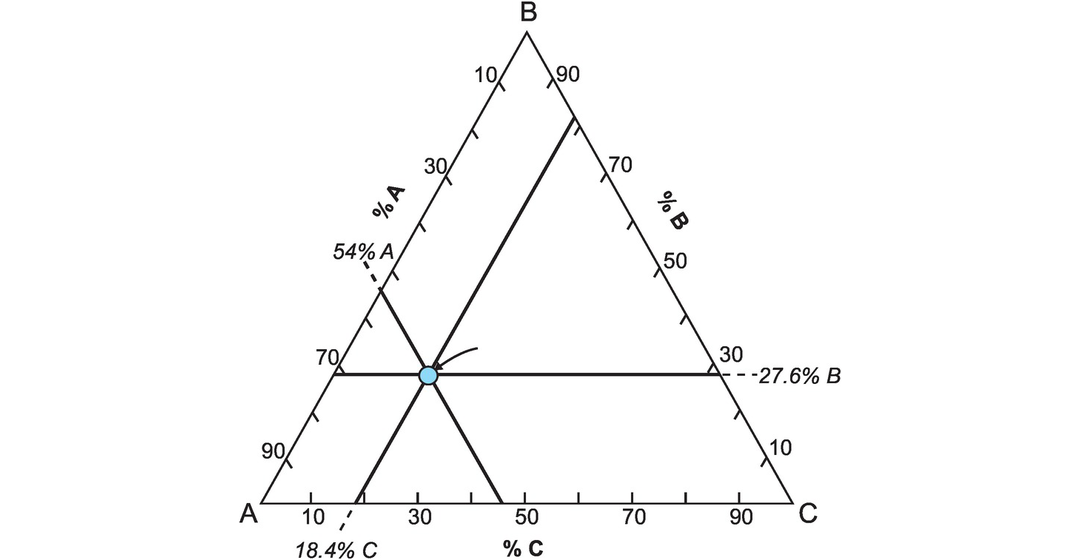

3.3.3 Ternary Diagrams