4.1 Introduction

A trace element may be defined as an element which is present in a rock in concentrations of less than 0.1 wt.%, that is, less than 1000 parts per million (ppm). This means that it is not normally a stoichiometric constituent of the minerals which make up the rock; rather, it substitutes for one of the major elements in the structure of a host mineral. As a consequence of their low abundances, trace elements do not influence the chemical or physical properties of the system. There are, however, some limitations to this definition, for in igneous rocks the elements K and P behave as trace elements in mid-ocean ridge basalts, whereas in granites they form discrete minerals such as K-feldspar and, in the case of P, apatite or monazite. Unlike the major elements whose concentrations in the Earth’s crust vary over a relatively narrow range, the range of trace element concentrations may be several orders of magnitude.

As analytical methods have improved in both the range of elements that can be analysed and in the precision that their concentrations can be measured, trace element studies have become a vital part of modern petrology. This is because of the following:

1. Trace elements are more sensitive to geochemical processes than major elements and are therefore better at discriminating between petrological processes.

2. Their great chemical diversity coupled with the fact that different elements behave in different ways permits a wide range of possible processes to be assessed.

Thus, one of their principal uses is in the identification of geochemical processes. Particularly important is the fact that there are mathematical models to describe trace element distributions which allow the quantitative testing of petrological hypotheses. These are most applicable to processes in magmatic systems which are controlled by crystal–melt or crystal–fluid equilibria, but are also relevant to the processes involved in the formation of meteorites, sediments and ore deposits.

In this chapter we first develop some of the theory behind the distribution of trace elements and explain the physical laws used in trace element modelling. Then various methods of displaying trace element data are examined as a prelude to showing how trace elements might be used in identifying geological processes and in testing hypotheses.

4.1.1 The Classification of Trace Elements According to Their Geochemical Behaviour

A frequently used classification of the elements based upon their geochemical behaviour was proposed by Goldschmidt (1937), often regarded as the ‘father of geochemistry’. He proposed a fourfold classification, the nomenclature for which is still largely in current use:

To this quartet has been added (Lee, 2016):

Apart from the term ‘atmophile’, which is almost never used, this nomenclature is still in use today albeit with slightly different meanings. It is important to note, however, that some elements will demonstrate more than one type of geochemical behaviour.

A further classification of elements which is widely discussed is the cosmochemical classification relating to processes of planetary accretion. In this case elements are classified according to their condensation temperature from gaseous to solid or liquid state during the cooling of a solar nebula. This classification is relevant to the formation of meteorites and the earliest stages of Earth formation, and so is useful when discussing large-scale planetary features, although is less relevant when considering crust and mantle geochemistry. Elements are grouped as follows according to condensation temperature in kelvin (K):

Highly refractory (>1700 K), to include Re, Os, W, Zr and Hf

Moderately refractory (1300–1500 K), to include Mg, Si, Cr, Fe, Co and Ni

Moderately volatile (1100–1500 K), to include Cu, Ba and Mn

Volatile (700–1100 K), to include Na, K, S and Rb

Highly volatile (<700 K), to include Pb, O, C, N, H and noble gases

Trace elements are often studied in groups, and deviations from group behaviour or systematic changes in behaviour within the group are used as an indicator of petrological processes. The association of like trace elements also helps to simplify what can otherwise be a very unwieldy data set. Most geochemically important trace elements can be classified either on the basis of their position in the periodic table or according to their behaviour in magmatic systems, as discussed below.

4.1.1.1 Trace Element Groupings in the Periodic Table

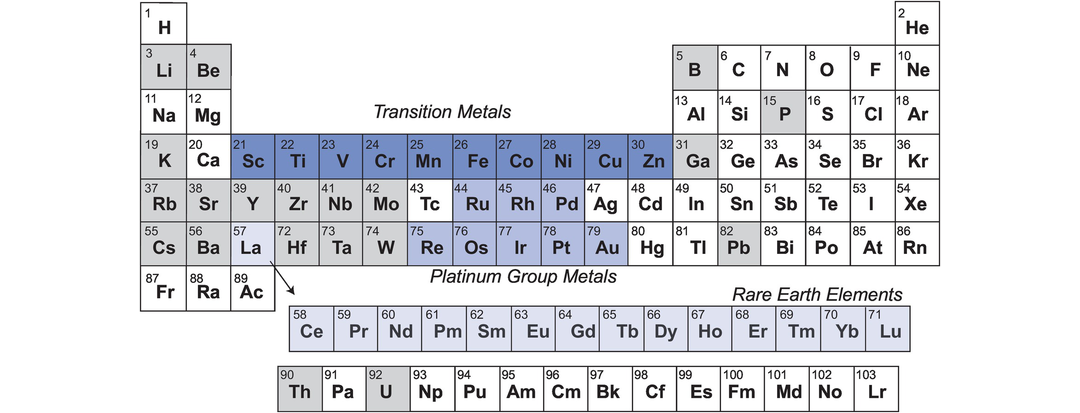

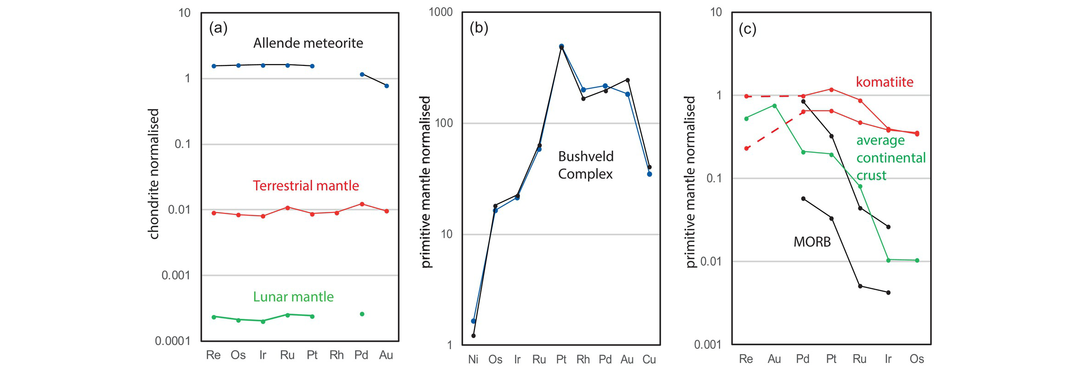

Goldschmidt‘s geochemical classification of the elements presented above can be interpreted in terms of location within the periodic table. Here specific elemental groups are highlighted for their particular importance in trace element geochemistry (Figure 4.1). The most obvious in this respect are the lanthanides, elements with atomic numbers 57–71 (La to Lu), or the rare earth elements (REE) as they are usually called in geochemistry. Y also behaves in a manner similar to the REE. The platinum group elements (PGE, or platinum group metals, PGM) include elements with atomic numbers 44–46 – Ru, Rh, Pd – and 76–79 – Os, Ir, Pt. They are known as the noble metals if they also include Au. An expanded grouping of the PGE is known as the highly siderophile elements (HSE) and includes Os, Ir, Ru, Rh, Pt and Pd, together with Re and Au, which have some similar properties. This group can be used in understanding the large-scale processes associated with planetary accretion and differentiation, in particular, core formation, due to their affinity for metal relative to silicate minerals. The term transition metals (atomic numbers 21–30, Sc–Zn) is usually restricted to the first transition series and includes the two major elements Fe and Mn.

The periodic table of the elements. The three main groups of trace elements which are treated together in geochemistry because of their relative positions on the periodic table are highlighted. These are the elements of the first transition series (transition metals), the platinum group elements + Re and Au (platinum group metals) and the rare earth elements. Other trace elements important in geochemistry are shaded light grey.

The elements in each of these respective groups have similar chemical properties and for this reason are expected to show similar geochemical behaviour. However, this may not always be the case, for geological processes can take advantage of subtle chemical differences within an elemental group and fractionate elements one from the other. Thus, one of the tasks of trace element geochemistry is to discover which geological processes may have this effect and to quantify the extent of particular processes.

4.1.1.2 Trace Element Behaviour in Magmatic Systems

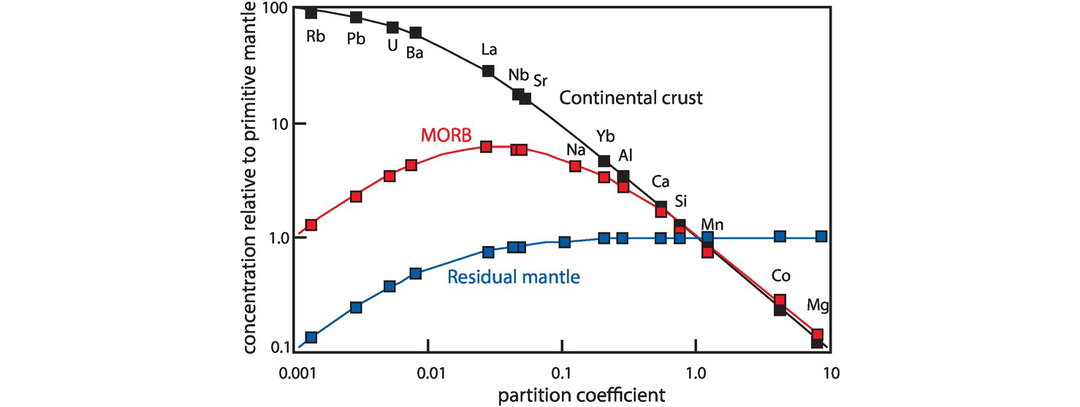

When the Earth’s mantle is melted, trace elements display a preference either for the melt phase or the solid (mineral) phase. Trace elements whose preference is the mineral phase are described as compatible, whereas elements whose preference is to remain in the melt are described as incompatible; in other words, they are incompatible in the mineral structure and will leave at the first available opportunity. In detail there are degrees of compatibility and incompatibility, and so trace elements may be described as moderately incompatible or highly incompatible. The degree of trace element incompatibility is quantified by the mineral-melt partition coefficient (see Section 4.2.1). Trace element incompatibility is also the basis for the ordering of elements in mantle normalised trace element diagrams (see Section 4.4). The degree of incompatibility will vary between melts of different compositions. For example, P is incompatible in mantle minerals and during partial melting will be concentrated in the melt. In granites, however, even though P is present as a trace element it is compatible because it is accommodated in the structure of the accessory mineral phases apatite and monazite.

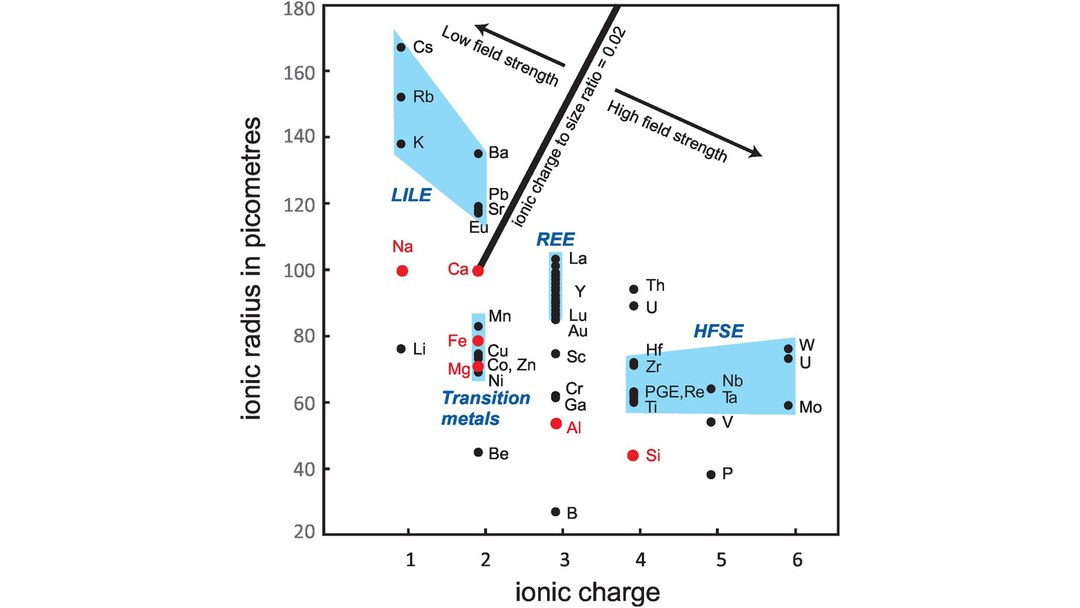

It is sometimes helpful to subdivide the incompatible elements on the basis of their charge to size ratio. This property is often described as the field strength and may be thought of as the electrostatic charge per unit surface area of the cation. It is also described as the ionic potential of an element and is quantified as the ratio of the valence to the ionic radius, which is measured in picometres. Figure 4.2 shows a plot of ionic size versus charge for a range of trace elements. In addition, some major elements are shown to indicate where atomic substitutions most commonly occur. Small highly charged cations located in the lower right of the diagram are known as high field strength (HFS) cations (ionic potential > 0.02). The broadest definition of HFS elements (HFSE) includes the trivalent REE, Y, Sc, Th, U and the PGE, although more commonly the term is restricted to those elements that are tetravalent (Hf, Ti, Zr), pentavalent (Nb, Ta) and hexavalent (W, Mo). With the exception of Mo, the HFS elements are commonly fluid immobile and therefore their concentrations normally remain unchanged during weathering or metamorphism.

Plot of ionic radiius (measured in picometres, 10−12 m) versus ionic charge for incompatible trace elements of geological interest. Major elements (in red) indicate where trace element ionic substitutions will most readily occur. An ionic potential (charge to size ratio) of 0.02 subdivides the incompatible elements into low field strength (LFS) elements (also known as large ion lithophile elements, LILE) and high field strength elements (HFSE). The ionic radii are from Shannon (1976) and are quoted for six-fold coordination to allow a comparison between all elements.

Elements with ionic radii too large to fit into most silicate minerals and with a small charge are known as low field strength cations (ionic potential < 0.02). They are also known as the large ion lithophile elements (LILE) and are primarily the alkali and alkali earth elements (Figure 4.2). The term ‘LILE’ has been used in a number of different ways, but Chauvel and Rudnick (2018) recommend that the term be restricted to lithophile trace elements having large radius to charge ratios and which have ionic radii greater than those of Ca2+ and Na1+ (100 and 102 picometers, respectively) – these are the largest cations commonly found in rock-forming minerals. By this definition, the list of LILE is restricted to K, Rb, Sr, Cs, Ba, Pb2+ and Eu2+. LILE elements are commonly fluid mobile elements, and so their primary concentrations may change during post-solidus alteration.

Other important trace elements include the following:

The small cations such as Li+, Be2+, B3+, P5+ which are all moderately incompatible.

Ga, which substitutes for Al and so is concentrated in Al-rich minerals in the crust; during partial melting of the mantle, Ga is incompatible in most phases, including garnet, but is compatible in spinel (Davis et al., 2013).

Although not trace elements, volatiles with low solubility such as CO2 in mafic melts may also behave as trace elements (Saal et al., 2002).

Some elements have very similar charge and size, and observing their geochemical behaviour can be particularly important. These include the following elements:

Hf and Zr, and Nb and Ta; both element pairs are almost identical in size and charge and show very similar geochemical behaviour. Nevertheless, in some circumstances the element pairs are fractionated; thus, the ratios Hf/Zr and Nb/Ta are important geochemical parameters.

U and Th have a similar charge and size and both are highly incompatible in magmatic systems but may be fractionated with Th being the more incompatible; U/Th may also be fractionated during fluid–rock interaction.

Amongst the low field strength, large ion lithophile cations, Sr, divalent Eu and divalent Pb have almost identical ionic radii and charge.

A version of the ionic charge to size ratio diagram is given by Chauvel (2018) contoured for element incompatibility in the mineral clinopyroxene. The diagram shows that the most compatible elements are those with an ionic charge and size closest to the major cations in the host mineral (in this case, divalent Ca, Mg and Fe). Incompatibility increases with the difference in charge and size from that of the major cations, such that the monovalent LILE and the pentavalent HFSE are highly incompatible.

4.1.1.3 Trace Elements of Economic Significance

Some trace elements may have strategic importance in local economies and these have become known as the critical metals. These are metals that are economically important for industry but their supply may be limited because they can be obtained from only a few locations worldwide (Moss et al., 2011). They include elements such as the REE, the PGE, Ga, Sb, In, Be, Co, W, Nb and Ta. The critical metals are important in the electronics industry, and a subset of them, known as the E-tech elements, are important in the development of renewable energy technologies (Grandell et al., 2016). These elements include Co, Ga, In, Te, Li and the heavy REE (HREE). Some of these elements, such as indium (In, atomic number 49) and tellurium (Te, atomic number 52), are very rare and not well understood geochemically.

4.2 Physical Controls on Trace Element Distribution

Modern quantitative trace element geochemistry assumes that trace elements are present in a mineral in solid solution through substitution. The principal variables are the charge and size of the trace ion relative to the charge and size of the lattice site. These properties were recognised by Goldschmidt (1937), who through empirical observation proposed a series of qualitative rules to govern the priority which is given to ions with similar charge and size competing to enter a given crystal lattice. However, modern studies of trace element partitioning have shown that Goldschmidt’s rules are not universally correct, for it is also necessary to also consider the energetics of the crystal lattice itself (Blundy and Wood, 2003; also see Section 4.2.1.2).

More recently, this approach has been quantified and trace element distributions are now described in terms of equilibrium thermodynamics. Trace elements may mix in their host mineral in either an ideal or a non-ideal way. Their very low concentrations, however, lead to relatively simple relationships between composition and activity. When mixing is ideal, the relationship between activity and composition is given by Raoult’s law, that is,

where ai is the activity of trace element i in the host mineral and Xi is its composition.

If the trace element interacts with the major components of the host mineral, the activity will depart from the ideal mixing relationship, and at low concentrations the activity composition relations obey Henry’s law. This states that at equilibrium the activity of a trace element i in mineral j (aij) is directly proportional to its composition:

where kij is the Henry’s law constant – a proportionality constant (or activity coefficient) for trace element i in mineral j and where Xij is small. In fact, White (2013) suggests that adherence to Henry’s law can be a helpful way of defining a trace element.

A detailed study by Drake and Holloway (1981) demonstrated that for elements that are homovalent (of identical charge) Henry’s law seems to apply through a wide range of trace element concentrations. Similarly, Wood and Blundy (1997) showed that REE partitioning in clinopyroxene follows Henry’s law behaviour even though the REE concentrations in clinopyroxene ranged from tens to thousands of ppm. However, where the substitutions are heterovalent and the mineral structure has to be electrostatically balanced either through a vacancy or an ion with a balancing charge, then Henry’s law may not always apply. In this case, partitioning may depend upon the concentration of specific ions. For example, Grant and Wood (2010) showed this to be the case for Sc partitioning in olivine in which DolSc (the partition coefficient for Sc between olivine and melt) varied according to the concentration of Sc in the melt. Henry’s law also ceases to apply at very high concentrations, although the point at which this takes place cannot be easily predicted and must be determined for each individual system. For example, Prowatke and Klemme (2006) demonstrated that Sm partitioning into titanite showed a dependence on the bulk composition of both the melt and the titanites themselves, and that Henry’s law ceased to apply at bulk compositions containing several thousand ppm Sm. In the case where trace elements form the essential structural constituent of a minor phase, such as Zr in zircon, Henry’s law behaviour does not strictly apply.

However, for the majority of trace elements in most rock-forming minerals, the relatively simple mixing relationships between trace elements and major elements in their host minerals means that the distribution of trace elements between minerals and melt can be quantified in a simple way, as outlined below.

4.2.1 Partition Coefficients

The distribution of trace elements between phases may be described by a partition coefficient or a distribution coefficient (McIntire, 1963). It is used extensively in trace element geochemistry and describes the equilibrium distribution of a trace element between a mineral and a melt. Where the partition coefficient is calculated as a weight fraction, typical for trace element geochemistry, it may also be known as the Nernst partition coefficient. The distribution coefficient is defined by

where

A mineral-melt partition coefficient of 1.0 indicates that the element is equally distributed between the mineral and the melt. A value of greater than 1.0 implies that the trace element has a ‘preference’ for the mineral (solid) phase and in the mineral–melt system under investigation is a compatible element. A value of less than 1.0 implies that the trace element has a ‘preference’ for the melt and is an incompatible element.

A bulk partition coefficient is a partition coefficient calculated for a rock for a specific element from the partition coefficients of the constituent minerals weighted according to their proportions. It is defined by the expression

where Di is the bulk partition coefficient for element i, and x1 and D1, etc., are the percentage proportion and partition coefficient for element i in mineral 1, respectively. For example, in a rock containing 50% olivine, 30% orthopyroxene and 20% clinopyroxene, the bulk partition coefficient (D) for the trace element i would be

4.2.1.1 Measuring Partition Coefficients

Partition coefficients can be determined in natural systems from the analysis of minerals and their glassy matrix in rapidly cooled volcanic rocks. Many of the early mineral-melt partition coefficient measurements were obtained in this way by carefully analysing a clean mineral separate of unzoned minerals and their glassy matrix to obtain mineral-matrix or phenocryst-matrix partition coefficients (Philpotts and Schnetzler, 1970). More recently, this approach has been extended to the analysis of melt inclusions in phenocryst phases. However, there are a number of difficulties with the early approaches to trace element partition coefficient measurement using phenocryst–matrix pairs, not least the problem of ensuring equilibrium in natural samples. Other difficulties include the presence of mineral inclusions in samples where bulk minerals have been analysed.

An alternative to using natural systems is to use experimental data in which synthetic or natural starting materials are doped with the element of interest. This approach has the advantage that variations in temperature, pressure and oxygen fugacity can be more carefully monitored than in natural systems. However, in experimental studies of trace element partitioning it is important to attempt to establish Henry’s law behaviour, for this then allows the results to be extrapolated to other compositions and used in petrogenetic modelling (Dunn, 1987). More recently, these approaches have been enhanced with the development of high-precision microbeam techniques which allow the precise measurement of low trace element concentrations to be made in situ in experimental charges. These methods include the field emission electron microprobe, laser ICPMS and ion-probe (SIMS) and are discussed in Section 1.4. A full discussion of potential sources of error in experimental partition coefficient determination is given by Neilson et al. (2017).

As the volume of experimental data has increased it has become clear that many different variables may influence the value of a partition coefficient, and these may be categorised into two groups. First, there are the effects of crystal chemistry. This is amenable to quantification using lattice strain theory as discussed in Section 4.2.1.2. A second major control on the value of trace element partition coefficients is the composition of the melt, based on the understanding that melt structure and degree of melt polymerisation will strongly influence the extent to which a melt might accommodate trace elements (see Section 4.2.1.3).

4.2.1.2 Calculating Partition Coefficients Using Lattice Strain Theory

To experimentally determine the partition coefficients for all trace elements in a range of melt compositions at different pressures and temperatures is an almost impossible task. In addition, it is often assumed that mineral-melt partition coefficients are constant during a given magmatic process, although thermodynamically this is most unlikely (Wood and Blundy, 2014). Thus, a number of workers (Beattie, 1994; Blundy and Wood, 1994, 2003; Wood and Blundy, 1997, 2014) have sought to develop predictive models of trace element partitioning based upon a thermodynamic extrapolation of experimental data. This approach has led to the development of ‘lattice strain’ models which are, in effect, the quantification of the qualitative ideas developed by Goldschmidt.

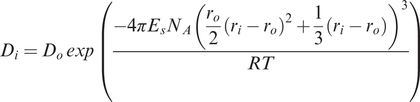

The lattice strain approach was developed by Nagasawa (1966) and Brice (1975) and is based upon the concept that trace ions in a crystal lattice can be treated as charged point defects in the structure. The disruption of the lattice around these point defects is minimised by relaxing the neighbouring ions and distributing the surplus elastic or electrostatic energy through the lattice. The basic equation, often known as the Brice equation, for a partition coefficient D for element i is

where

Di is the partition coefficient

Do is the strain-free partition coefficient, i.e., the partition coefficient for an ion the same size as that of the site and the same charge as i which enters the lattice without strain

Es is the effective Young’s modulus of the site (the elastic response to lattice strain). Blundy and Wood (1994) showed that elasticity varies linearly with the charge of the cation.

ro is the radius of the site

ri is the radius of ion i

R is the gas constant

T is temperature in Kelvin

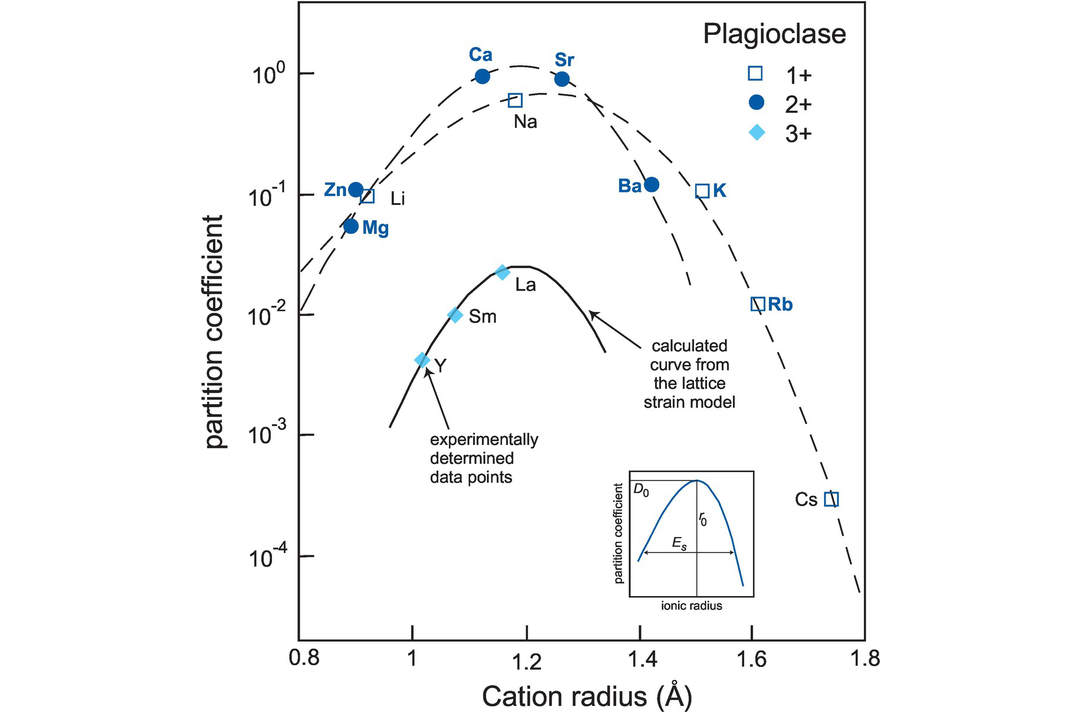

Two tests of the lattice strain model demonstrate its utility. First, on a cation radius versus partition coefficient diagram of the type first pioneered by Onuma et al. (1968) and often known as an Onuma diagram, comparisons between measured partition coefficients and those calculated using the equation of Brice (1975) (Eq. 4.5) show very good agreement (Blundy and Wood, 1994) indicating that the model is appropriate for cations with a range of ionic charge in a number of different silicate phases (Figure 4.3). Second, the lattice strain model has a powerful predictive capability which allows partition coefficients to be calculated for elements where there are no experimental data from those whose values are already known. Blundy and Wood (1994) calculated partition coefficients for Ra in plagioclase and clinopyroxene at a time when these were not experimentally determined. Subsequent experimental studies found excellent agreement between the measured and calculated values.

A plot of experimentally determined partition coefficients (expressed as log to the base 10) versus ionic radius (in angstroms: 10−10 m) for trace elements in plagioclase in equilibrium with silicate melt in the system diopside–albite–anorthite (after Wood and Blundy, 1997; adapted by permission of Springer-Nature). Diagrams of this type are known as Onuma diagrams. The curves drawn through the cations of equal valency are calculated from the lattice strain model (Eq. 4.5). The measured partition coefficients for mono-, di- and trivalent cations define separate parabolic curves which become tighter as the charge on the cation increases. This is due to the increase in the effect of Young’s modulus on the site with increasing charge. The peak of the parabola corresponds to the ‘best fit’ ionic radius ro and partition coefficient Do which is the optimum size of the site in plagioclase (see inset). Partition coefficients decrease as the size of the site deviates either positively or negatively from ro. Deviations from the anticipated parabolic pattern may reveal controls on trace element partitioning other than those of the size and charge of the cation. Onuma diagrams can also be used to estimate the size of a distribution coefficient when measurements have been made for a similar element. The inset diagram illustrates the three key parameters of the lattice strain model: ro, the radius of the site; Do, the strain-free partition coefficient; and Es, the elastic response of that site to lattice strain as measured by Young’s modulus.

Thermodynamic theory indicates that the lattice strain parameters (Do, ro and Es) are a function of key variables such as pressure, temperature and composition, and increasingly the trend is for the lattice strain parameters to be parameterised from a range of experimental studies. These equations can then be used to calculate partition coefficients for a specific set of conditions for a given group of trace elements. Wood and Blundy (1997) show how this methodology may be used to quantify partition coefficients for REE and Y in clinopyroxene and allows for the precise quantification of DREE during the polybaric fractional melting of the mantle.

4.2.1.3 Physical Controls on the Value of Partition Coefficients in Mineral-Melt Systems

Thus far we have shown how ionic size and charge are important parameters in the partitioning of trace elements between minerals and melt and how these properties may be quantified from experimental data. We have also noted that consideration of mineral-melt equilibria from a thermodynamic standpoint indicates that partitioning is also governed by properties such as melt composition, temperature and pressure. In the section that follows we illustrate empirically the effects of these and other intensive variables on the size of mineral-melt partition coefficients.

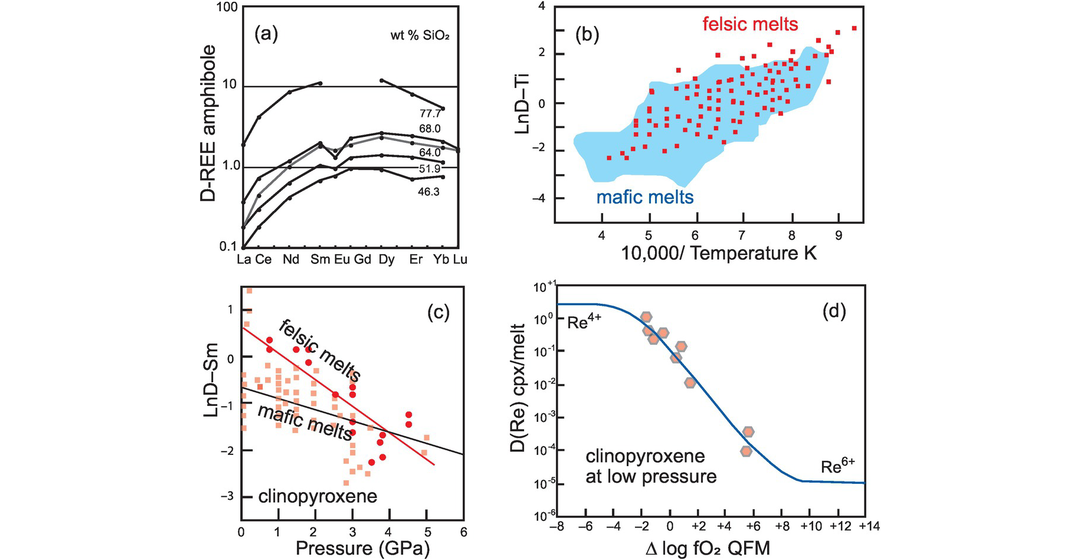

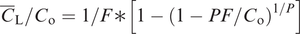

(a) Composition. Two very significant studies from the 1970s demonstrate that trace elements show distinct preferences when partitioned between immiscible acid and basic melts (Watson, 1976; Ryerson and Hess, 1978), indicating that melt composition exerts a major control on trace element partitioning. Typically, the values of partition coefficients are higher in more siliceous melts, sometimes by as much as an order of magnitude, as illustrated with respect to the partitioning of the REE between hornblende and basaltic, intermediate and felsic melts (Figure 4.4a).

(a) Partition coefficients for REE between amphibole and silicate melt show an increase with increasing SiO2 content of the melt (data from Tiepolo et al., 2007). In mafic melts (low silica content) light REE are incompatible and middle and heavy REE are compatible. In felsic melts (high silica content) all the REE are compatible. (b) Variation in partition coefficient for Ti in clinopyroxene with temperature. LnD–Ti increases with falling temperature (increasing 10,000/K). Mafic melts are represented by the shaded field and felsic melts by squares (after Bédard, 2014; with permission from John Wiley & Sons). (c) Variation in partition coefficient for Sm in clinopyroxene with pressure. LnD–Sm decreases with increasing pressure. The solid red line and circular data points are for felsic melts, the grey line and square data points are for mafic melts (after Bédard, 2014; with permission from John Wiley and Sons). (d) Variation in partition coefficients for Re in clinopyroxene with changing oxygen fugacity. At high oxygen fugacities the dominant ion is Re4+ which is compatible. At low oxygen fugacities the dominant ion is Re6+, which is strongly incompatible.

Much of this compositional dependence is related to structural changes in the melt phase and the increased polymerisation of the more silica-rich melts. There are two commonly used models for describing the degree of structural organisation in a melt. There is the NBO/T notation in which the ratio of non-bridging oxygen (NBO) ions is expressed relative to the proportion of tetrahedrally coordinated cations (T) ions (Si and Al). It has been shown that with increasing melt polymerisation there is a decrease in NBO ions which leads to fewer sites available in the melt to accommodate trace elements such as the REE. This gives rise to higher partition coefficients for the REE. In contrast, partition coefficients for cations with a low charge/size ratio decrease with increasing melt polymerisation due to their coupled substitution with Al (Bennett et al., 2004). The parameter NBO/T can be calculated using the method of Mysen (1988) and varies between 4.0 for an unpolymerised melt to less than 1.0 for a 3D network. This notation has been used as a measure of melt composition in trace element partitioning studies by Schmidt et al. (2006).

A slightly different notation is the Xnf/X parameter where Xnf is the sum of the molar fraction of the network-forming (nf) cations (Si and some Al) normalised to X, the sum of all the cations calculated on a molar basis. This has been used to assess changes in melt structure in amphibole trace element partitioning experiments by Tiepolo et al. (2001, 2007).

In addition to the importance of the silica content of melts on the magnitude of trace element partition coefficients, other elements may also play an important role. Bennett et al. (2004) show that the Na content of a melt in the Na2O–CMAS system has an important effect on trace element partitioning between clinopyroxene and melt. In more sodic melts partition coefficients of the more highly charged (3+ and 4+) ions are higher by up to an order of magnitude relative to values in the ‘pure’ CMAS system. In addition, in some phases compositional controls on element partitioning may be exerted by ‘local’ crystal-chemical controls in specific mineral phases. Examples are given below in the mineral data for basalt partition coefficients (Section 4.2.1.5).

(b) Temperature. A good example of the control of temperature on partition coefficients comes from the compilation of experimental data by Bédard (2014) for calcic clinopyroxenes. These results show a strong negative correlation between

(c) Pressure. One of the more convincing demonstrations of the effect of pressure on partition coefficients is the work of Green and Pearson (1983, 1986) on the partitioning of REE between sphene and an intermediate silicic liquid. Within a small compositional range (56–61 wt.% SiO2) at 1000°C they showed that there is a measurable increase in partition coefficient with increasing pressure from 7.5 to 30 kb. A more recent and petrologically important example is that of REE partitioning in clinopyroxene by Bédard (2014). He reviewed a voluminous amount of experimental data and showed that in both mafic and felsic melts DREE decreases with increasing pressure (illustrated with DSm in Figure 4.4c). Given that clinopyroxene is the principal host of REE in mantle rocks this observation has important implications for melting at different depths in the mantle. Similarly, some HFSE (notably Ti and Zr) show a similar property and in some amphiboles DTi,Zr decreases with increasing pressure (Dalpe and Baker, 2000).

(d) Oxygen fugacity and the importance of redox-sensitive trace elements. In experimental studies oxygen fugacity (fO2) is often buffered and this is normally reported relative to the quartz–fayalite–magnetite (QFM) oxygen buffer. fO2 values are a function of temperature, and so reference is sometimes made to the QFM fO2–T buffer curve. The QFM buffer tends to be used as a reference point since this is thought to approximate to the oxidation state of the upper mantle. However, in natural magmatic systems oxygen fugacity can vary by several orders of magnitude, and so the redox effect on trace element partitioning for heterovalent cations can be significant. Elements in this category include the first-row transition series elements, the PGE + Re and Eu, although experimental studies show that the most important redox-sensitive trace elements can be reduced to just V, Re, Eu and the major element Fe. As an example, the element Re may form the ions Re4+ and Re6+ in terrestrial magmas. As the Re ion becomes more oxidised there is a reduction in ionic size from 63 to 55 pm (10−12 m) (Shannon, 1976). This reduction in ionic size influences the partitioning of the element into specific sites in the mineral lattice. Mallmann and O’Neill (2007) showed that Re4+ is moderately compatible in garnet and clinopyroxene, slightly incompatible in orthopyroxene and spinel, and incompatible in olivine, but Re6+ is incompatible in all phases (Figure 4.4d). In a similar way the trace element V has the potential to form the ions V2+, V3+, V4+ and V5+ with the resultant reduction in ionic radius from 79 to 54 pm, for six-fold coordination, with increased oxidation (Shannon, 1976). Mallmann and O’Neill (2009) explored the change in the measured partition coefficients for DV during mantle melting over a wide range of redox conditions (−13 to +11 fO2 relative to the quartz–fayalite–magnetite oxygen buffer) – this covers the known redox conditions of the entire inner solar system. They showed that at low oxygen fugacity V is compatible in the phases olivine, pyroxene and spinel, whereas at high oxygen fugacity it is highly incompatible. The systematic change in partition coefficient with increasing oxygen fugacity for elements such V and Re means that their concentrations in basaltic melts will vary according to the redox conditions of mantle melting. These data have been inverted to calculate the redox state of the mantle in different tectonic settings (see Mallmann and O’Neill, 2007, 2009, 2013, 2014; Laubier et al., 2014).

The most redox-sensitive trace element in plagioclase is Eu. At low oxygen fugacities europium forms Eu2+ whereas at high fugacities it forms Eu3+ and the two species behave very differently in their partitioning between plagioclase and a basaltic melt, for the larger Eu2+ ion is more compatible than the smaller Eu3+ in plagioclase. Eu when divalent follows Sr, whereas the trivalent oxidised form follows the REE (Drake and Weill, 1975; Aigner-Torres et al., 2007). The net result of this is that the partitioning behaviour of Eu may depart from that of the other REE leading to an Eu anomaly in the REE pattern.

(e) Water content of the melt. The addition of water to a silicate melt has two opposing effects on partition coefficients. First, since the presence of water lowers the crystallisation temperature of a melt, this may cause partition coefficients to increase, but, second, the presence of water may the lower the activity and activity coefficients of the trace components in the melt such that partition coefficients may decrease (Wood and Blundy, 2014). Gaetani et al. (2003) found that during the partial melting of hydrous peridotite clinopyroxene REE partition coefficients were lower than predicted. They attributed this reduction in DREE to a change in the degree of melt polymerisation caused by the addition of water to the melt. In plagioclase Bédard (2006) noted that DTi and DREE increase as the water content of the melt increases.

4.2.1.4 Selecting an Appropriate Partition Coefficient

It is clear from the foregoing discussion that selecting an appropriate partition coefficient is not simple given the large number of variables to consider. A further complexity is the observation that mineral-melt partition coefficients are not constant during differentiation processes, for as a melt differentiates the composition of the melt, the pressure and the temperature will all change (Wood and Blundy, 2014). Sometimes the effects of the different variables can be inter-related, as, for example, when the liquidus temperature of a melt is a function of composition as in the case for olivine in a magnesian melt. At other times the effects of two different variables may cancel each other out. An example would be the contrasting effects of increased pressure, which serves to increase the partition coefficient, and increasing temperature, which reduces it.

Given the important control of melt composition on the size of partition coefficients, Nielsen and Drake (1979) and Neilsen and Dungan (1983) sought to minimise the impact of this variable by considering melt composition as a two-lattice melt model. In this model, the melt is assumed to be made up of two independent lattices comprising the network-forming and the network-modifying cations and anions. Partition coefficients are then parameterised against complex functions of melt chemistry. However, as Bédard (2005) pointed out there are some difficulties with this approach. First, some cations can fulfil multiple structural roles within the melt. In addition, the parameterisation of D-values requires that the melt composition be known exactly, and while this might work in laboratory experiments it cannot always be applied to natural rock samples.

Given that not all trace element data is adequately parameterised, a more empirical approach is taken here. Tables of partition coefficients (Tables 4.1–4.4) have been compiled from the literature to illustrate ‘indicative’ partition coefficients. It is recommended that these are used as a guide in petrological modelling and should not be taken as definitive. For a particular petrological model, partition coefficients should be taken from experimental studies that most closely match those of the conditions being modelled. The partition coefficients tabulated here are organised by melt composition and are drawn from the huge wealth of experimental work on trace element partitioning now published.

Much of the older partition coefficient (Kd) data is summarised in the GERM (Geochemical Earth Reference Model) database collated by R. Neilson at https://earthref.org/KDD/.https://earthref.org/GERM/tools/tep.htm. This database includes partition coefficients for a range of mineral species hosted in a wide range of rock types and has the advantage of being searchable, and the results can be downloaded into an Excel spreadsheet. In addition to individual experimental studies, there are some helpful syntheses such as the special volume of Lithos edited by Austreheim and Griffin (2000). In addition, compilations of partition coefficient data for specific minerals include olivine (Bédard, 2005), plagioclase (Bédard, 2006), orthopyroxene (Bédard, 2007), clinopyroxene (Bédard, 2014), and amphibole Tiepolo et al. (2007).

The longer-term aim of trace element partitioning studies is that all the relevant variables should be parameterised. This will include the composition of the mineral host, the composition of the melt, pressure and temperature. The extent to which this has already been accomplished is summarised in the review by Wood and Blundy (2014).

4.2.1.5 Partition Coefficients in Basalts

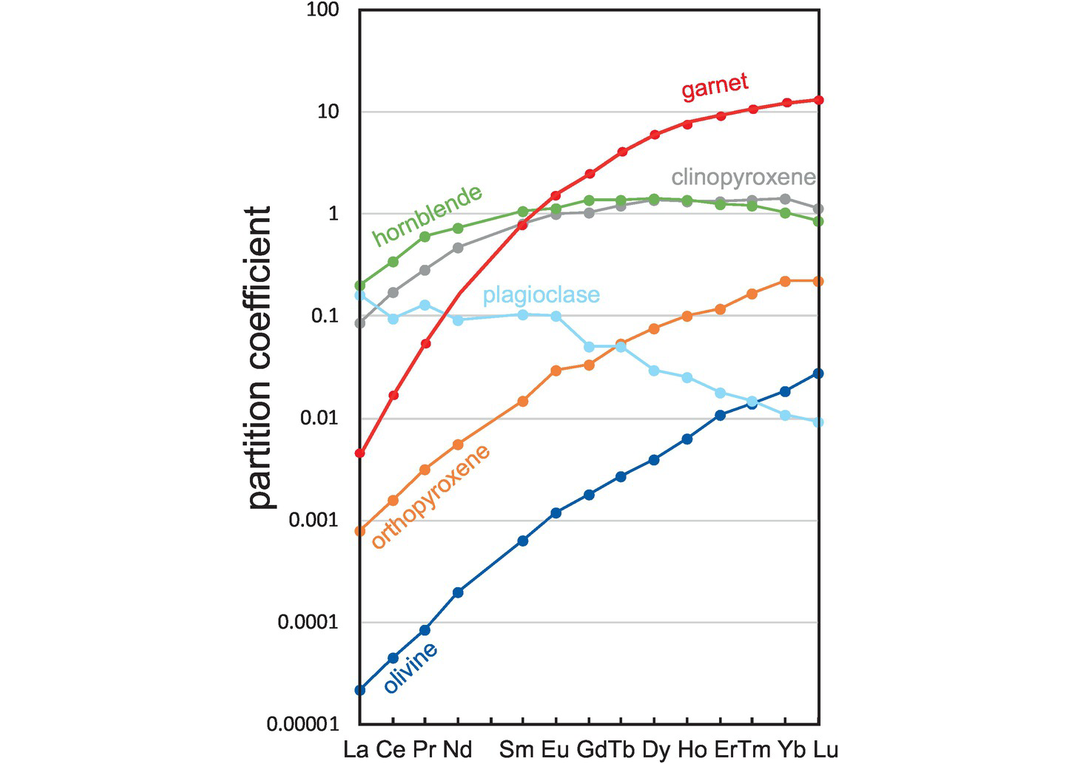

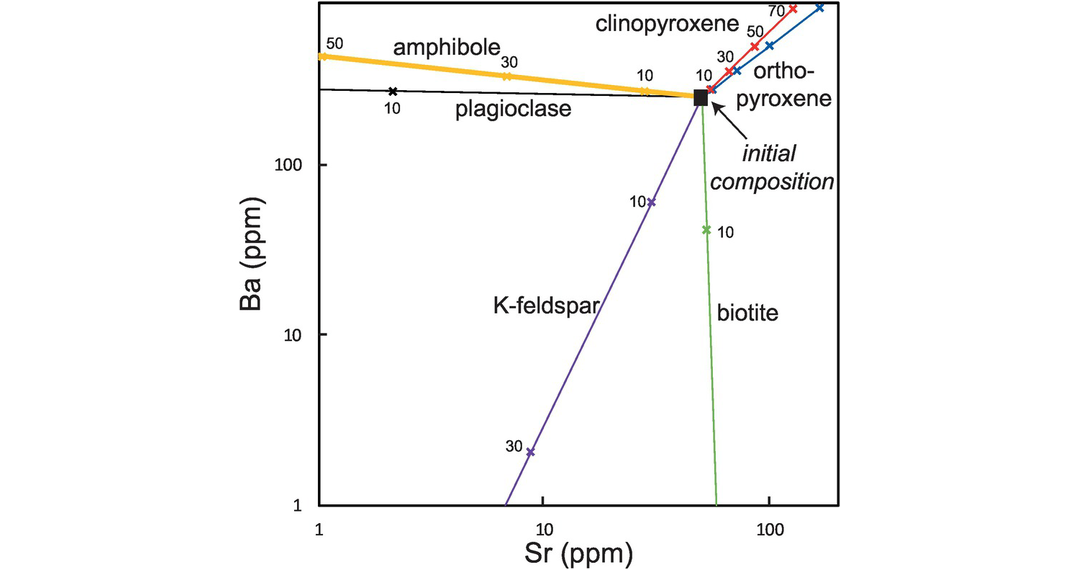

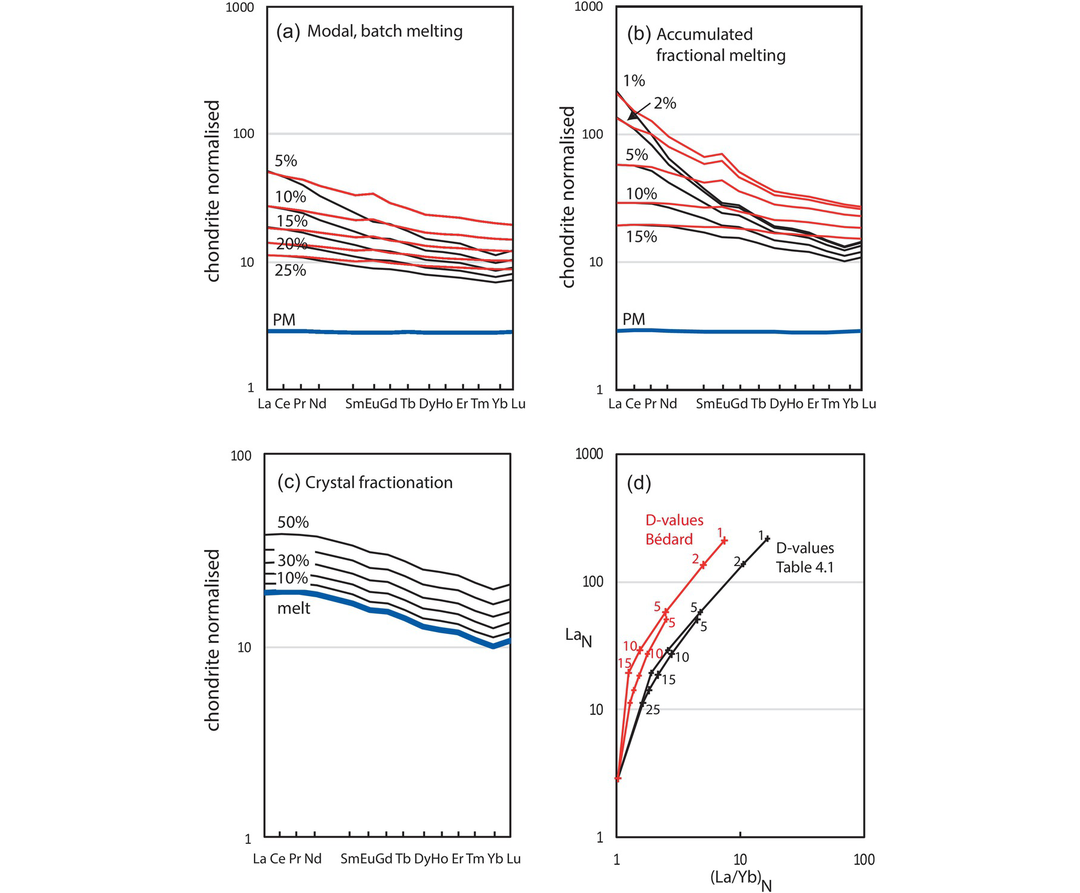

Some indicative partition coefficients for the geologically important trace elements in minerals in equilibrium with basaltic melts are listed in Table 4.1. The compilation is based upon a range of sources outlined below. Some REE values are interpolated, and those associated with some minerals common in mafic melts are shown in Figure 4.5. In the discussion that follows the relevant experimental conditions are included where possible. Averages are calculated as median values.

| Atomic number | Symbol | Name | Olivine | Orthopyroxene | Clinopyroxene | Garnet | Plagioclase | Ca-Amphibole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Li | Lithium | 0.198 | 0.200 | 0.200 | 0.022 | 0.2940 | 0.104 |

| 4 | Be | Beryllium | 0.248 | 0.016 | 0.047 | 0.003 | 0.5675 | 0.170 |

| 5 | B | Boron | 0.0055 | 0.018 | 0.036 | 0.0045 | 0.1860 | 0.010 |

| 19 | K | Potassium | 0.006845 | 0.0003 | 0.007 | 0.00061 | 0.2030 | 0.400 |

| 21 | Sc | Scandium | 0.1200 | 1.290 | 1.750 | 2.620 | 0.0160 | 4.940 |

| 22 | Ti | Titanium | 0.0096 | 0.759 | 0.380 | 0.290 | 0.0380 | 2.665 |

| 23 | V | Vanadium | 0.0896 | 0.856 | 2.900 | 3.600 | 0.0100 | 6.080 |

| 24 | Cr | Chromium | 1.180 | 3.520 | 8.100 | 2.010 | 0.0450 | 6.030 |

| 25 | Mn | Manganese | 1.632 | 1.410 | 0.895 | 0.865 | 0.0290 | nd |

| 27 | Co | Cobalt | 5.294 | 2.480 | 1.350 | 0.950 | 0.1490 | nd |

| 28 | Ni | Nickel | 24.010 | 7.380 | 2.600 | 5.100 | 0.1620 | nd |

| 29 | Cu | Copper | 0.1100 | nd | 0.360 | 0.575 | 0.1400 | nd |

| 30 | Zn | Zinc | 0.8300 | nd | 0.490 | 1.148 | 0.1300 | nd |

| 31 | Ga | Gallium | 0.1026 | 0.206 | 0.740 | 1.010 | 1.7000 | nd |

| 37 | Rb | Rubidium | 0.0007 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.0007 | 0.1140 | 0.090 |

| 38 | Sr | Strontium | 0.000138 | 0.0012 | 0.088 | 0.0074 | 1.6290 | 0.660 |

| 39 | Y | Yttrium | 0.007190 | 0.0950 | 0.670 | 8.5000 | 0.0371 | 1.325 |

| 40 | Zr | Zirconium | 0.008 | 0.0320 | 0.1115 | 0.7300 | 0.0010 | 0.370 |

| 41 | Nb | Niobium | 0.004 | 0.0013 | 0.0037 | 0.0055 | 0.0970 | 0.390 |

| 42 | Mo | Molybdenum | 0.1034 | 0.0039 | 0.014 | nd | nd | nd |

| 44 | Ru | Ruthenium | 1.0000 | nd | 2.400 | nd | nd | nd |

| 45 | Rh | Rhodium | 2.6960 | nd | 0.240 | nd | nd | nd |

| 46 | Pd | Palladium | 0.1000 | nd | < 0.3 | nd | nd | nd |

| 55 | Cs | Caesium | 0.0007 | nd | nd | nd | 0.5960 | 0.030 |

| 56 | Ba | Barium | 0.000023 | 0.000006 | 0.0002 | 0.00037 | 0.2470 | 0.385 |

| 57 | La | Lanthanum | 0.000022 | 0.0008 | 0.086 | 0.0047 | 0.1630 | 0.200 |

| 58 | Ce | Cerium | 0.000045 | 0.0016 | 0.175 | 0.0179 | 0.0960 | 0.350 |

| 59 | Pr | Praseodymium | 0.000085 | 0.0032 | 0.289 | 0.0593 | 0.1320 | 0.610 |

| 60 | Nd | Neodymium | 0.000200 | 0.0056 | 0.470 | 0.170 | 0.0908 | 0.730 |

| 62 | Sm | Samarium | 0.000636 | 0.0150 | 0.810 | 0.870 | 0.1060 | 1.075 |

| 63 | Eu | Europium | 0.001200 | 0.0300 | 1.000 | 1.630 | 0.1005 | 1.130 |

| 64 | Gd | Gadolinium | 0.001800 | 0.0340 | 1.040 | 2.550 | 0.0502 | 1.370 |

| 65 | Tb | Terbium | 0.002750 | 0.0540 | 1.220 | 4.200 | 0.0500 | 1.390 |

| 66 | Dy | Dysprosium | 0.004000 | 0.0770 | 1.400 | 6.200 | 0.0293 | 1.405 |

| 67 | Ho | Holmium | 0.006430 | 0.1000 | 1.350 | 8.200 | 0.0250 | 1.360 |

| 68 | Er | Erbium | 0.0110 | 0.1200 | 1.340 | 9.600 | 0.0181 | 1.275 |

| 69 | Tm | Thulium | 0.0140 | 0.17 | 1.380 | 11.100 | 0.0150 | 1.200 |

| 70 | Yb | Ytterbium | 0.0188 | 0.2200 | 1.420 | 12.600 | 0.0110 | 1.050 |

| 71 | Lu | Lutetium | 0.0280 | 0.2200 | 1.160 | 13.700 | 0.0093 | 0.850 |

| 72 | Hf | Hafnium | 0.0080 | 0.0600 | 0.383 | 0.480 | 0.0100 | 0.680 |

| 73 | Ta | Tantallum | 0.0300 | 0.0025 | 0.0239 | 0.0215 | 0.0750 | 0.335 |

| 75 | Re | Rhenium | 0.010 | 0.180 | 0.200 | 0.100 | nd | nd |

| 76 | Os | Osmium | 0.53437 | nd | 0.010 | nd | nd | nd |

| 77 | Ir | Iridium | 0.42619 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 78 | Pt | Platinum | 0.05140 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 79 | Au | Gold | 0.10000 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 82 | Pb | Lead | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.009 | 0.00034 | 1.5920 | 0.095 |

| 90 | Th | Thorium | 0.0018 | 0.00002 | 0.013 | 0.0015 | 0.3050 | 0.020 |

| 92 | U | Uranium | 0.0013 | 0.00004 | 0.006 | 0.0104 | 0.0107 | 0.010 |

Notes: nd, no data

REE mineral-melt partition coefficients between the major silicate minerals and basaltic melts.

(a) Olivine. Most partition coefficients for trace elements in olivine vary with the MgO content of the melt and with temperature, for the two variables are strongly correlated. Many of these partition coefficients have been parameterised by Bédard (2005). For the highly siderophile elements partition coefficients tend to vary as a function of fO2 with an increase in Di as fO2 decreases (Righter et al., 2004). For the REE, partition coefficients increase with increasing Al in olivine and decrease with increasing pressure and with Fo content of the olivine (Sun and Liang, 2013).

Olivine–melt partition coefficients for Ti, V, Mn, Co and Ni are taken from the experimental study of Laubier et al. (2014) for MORB melts (MgO = 8.56 wt.%) using median values for experimental runs between 1150 and 1190°C, at 0.1 MPa (atmospheric pressure) and fO2= QFM. Values for K, Cs, Pb, Th, U, Zr, Nb, Hf and Ta are from the parameterisation of Bédard (2005) for melts with 11 wt.% MgO. Values for Li, Be, Cu, Mo and Ga are also from the compilation of Bédard (2005). Values for the REE, Y, Sc, Sr and Ba are from Beattie (1994) using the recommended results for a komatiitic melt (experiment C10) as most appropriate for partial melting calculations. This experiment was conducted at 1495°C, at atmospheric pressure and at log fO2 = −4.7. Partition coefficients for the HSE Ru, Pd, Re and Au are from the experimental study of Righter et al. (2004) on a Hawaiian ankaramite (MgO = 9.75 wt.%) at atmospheric pressure and 1300°C, adjusted for the oxygen fugacity of natural systems. Os, Ir and Pt are from the compilation of Bédard (2005). Zn and Cr are from the GERM database.

(b) Orthopyroxene. Partition coefficient data for orthopyroxene in a basaltic melt for the REE, HFSE and Sr are from the experimental study of Green et al. (2000). This study shows that partition coefficients in orthopyroxene are strongly influenced by the Al content of the orthopyroxene. Average values were taken from experiments on a tholeiitic basalt (Mg# = 59), conducted under hydrous conditions at 2.0–7.5 GPa and 1080–1200°C and a fO2 between the Ni–NiO and magnetite–wustite buffers. Partition coefficients for Sc, Ti, V (at QFM) and Mn, Co, Ni, Ga are from the average experimental values of Laubier et al. (2014) in a MORB melt (MgO = 8.56 wt.%) at 1150–1190°C, 0.1MPa and fO2 = QFM to NNO+2. Partition coefficients for B, Be and Li are from the experimental study of Brenan et al. (1998) on a basaltic andesite at 1000–1350°C at atmospheric pressure. Data for K, Rb and Ba are from the GERM database and Cr is for Cr3+ from Mallmann and O’Neill (2009), who show that chromium partition coefficients for orthopyroxene increase with increasing oxygen fugacity.

(c) Clinopyroxene. Bédard (2014) showed that there is significant crystal chemical control in trace element partitioning in clinopyroxene. For example, there is a positive correlation between DTi and the tetrahedral Al content of clinopyroxenes implying a coupled Ti–Al substitution. A similar pattern was observed for DZr and DCo which also increase with increasing alkali content and silica content but decrease with increasing Mg# and CaO content (Bédard, 2014).

Here partition coefficient data for clinopyroxenes for the REE, HFSE and Sr are from the experimental study of Green et al. (2000) conducted on a tholeiitic basalt (Mg# = 59), as described above for orthopyroxene. In these experiments both the water content and the temperature of the melt influence trace element partitioning, although the effect of water is greater than that of temperature such that partition coefficients are lower under hydrous conditions. Sr values are pressure-sensitive and DSr increases with increasing pressure. Partition coefficient values for the elements Mo, Ru, Rh and Pd are from the compilation of Bédard (2014) and Be, B, Sc, K, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Ga, Rb, Re, Os, Pb, U and Th are from the GERM database; median values are used where there are multiple records.

(d) Garnet. Partition coefficient data for garnet for the REE, HFSE and Sr are from the experimental study of Green et al. (2000) on a tholeiitic basalt (Mg# = 59), as described above for orthopyroxene. As noted, both the water content and the temperature of the melt influence trace element partitioning such that at lower temperatures partition coefficients increase whereas under higher water contents partition coefficients decrease. Thus, the two effects tend to cancel each other out. Partition coefficients for Li and K are from the experimental study of Gaetani et al. (2003) on the melting of hydrous peridotite at 1.2 GPa and 1185°C. Partition coefficients for B, Be, Sc, Ti, V, Ni, Rb, Ba, Cr, Mn, Co, Ni, Zn, Ga, Pb, Th and U are from the GERM database. Re is reported as Re4+ at the conditions of the QFM buffer after Mallmann and O’Neill (2007).

(e) Plagioclase. Trace element partitioning between plagioclase and a basaltic melt is strongly dependent on the An content of the plagioclase and most partition coefficients increase with decreasing An content (Blundy and Wood, 1991; Bindeman et al., 1998; Bédard, 2006; Tepley et al., 2010). In addition, the partition coefficients of a small number of elements (Zr, Fe, Eu and Cr) are sensitive to fO2 (Aigner-Torres et al., 2007). There is no significant temperature control (Bindeman et al., 1998).

Partition coefficient data for plagioclase for the LILE, HFSE and first transition series elements were selected from the experimental database of Aigner-Torres et al. (2007) for the partitioning between plagioclase (An73–79) and MORB at 1200°C, atmospheric pressure and fO2 = QFM. Additional data for B, Be, V, Co, Ni, U and the REE + Y were obtained from the experimental studies of Bindeman et al. (1998) and Bindeman and Davis (2000). These experiments are for a basaltic andesite at T = 1426–1572 K, in air, at atmospheric pressure with plagioclase compositions between An75 to An77.2. Partition coefficients for Zn, Ga, Hf and Cu are from the GERM database.

(f) Amphibole. Trace element partitioning in amphibole is complex because of the number of different sites in the mineral lattice. There are three octahedral sites: M1, M2 and M3; an eight-fold M4 site occupied by Ca and Na; and a twelve-fold A-site occupied by Na and K or that may be vacant. The different sizes of these sites mean that they will exert different preferences for trace elements. Experimental studies show that partition coefficients in amphibole vary primarily as a function of the degree of melt polymerisation and are not strongly influenced by changes in P or T (Tiepolo et al., 2007). The effects of melt composition have been parameterised for the REE and Y as a function of Xnf/X (Tiepolo et al., 2007) (see Section 4.2.1.3). In addition, there are local crystal-chemical effects such as the Ca content (Wood and Blundy, 2014) and Mg# (Tiepolo et al., 2001), and for a few elements (Ti, Hf, Zr, Rb, Ba, La, Nd) oxygen fugacity also exerts a small effect (Dalpe and Baker, 2000).

The partition coefficient data listed here are for calcic-amphiboles and are from the review of Tiepolo et al. (2007). Experimental data were selected for melts in the range SiO2 = 48.1–52.4 wt.% at temperatures and pressures between 950 and 1070°C and 0.2–1.4 GPa and at fO2 = QFM − 2.

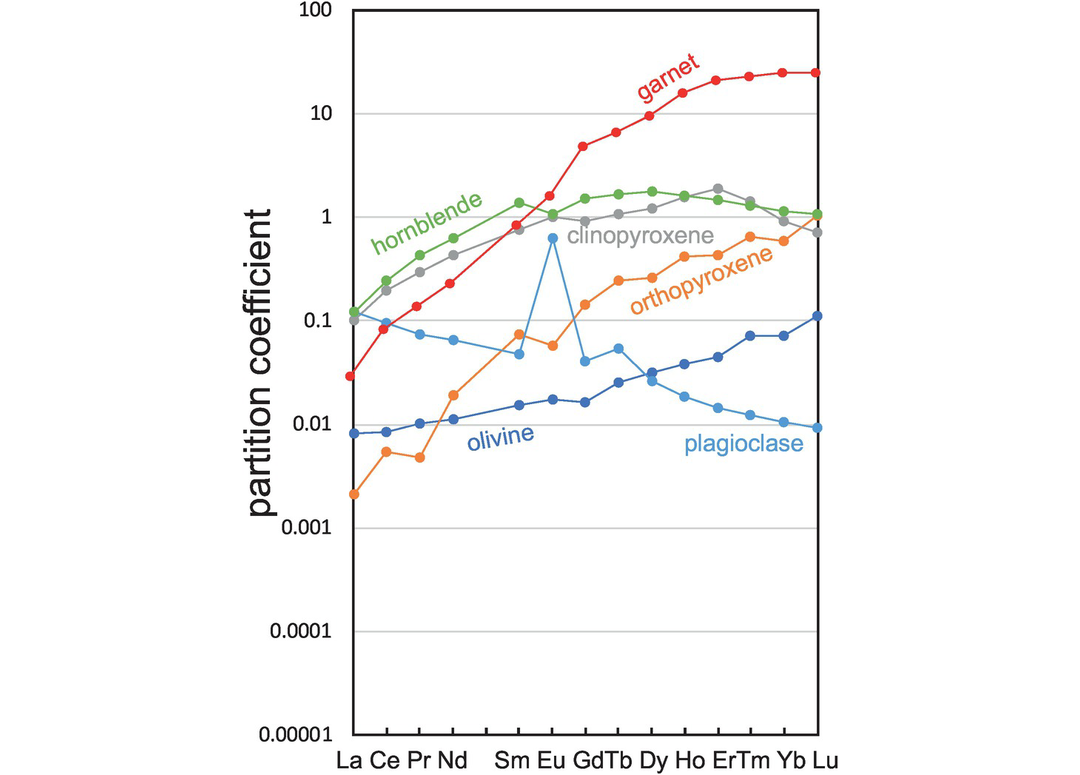

4.2.1.6 Partition Coefficients in Andesites

The partition coefficients for trace elements between rock-forming minerals and andesitic melts (57–63 wt.% SiO2 as defined in the TAS classification) are shown in Table 4.2 and Figure 4.6. This compilation is based upon the range of sources outlined below. Some REE values are interpolated. Where possible the relevant experimental conditions are included. Averages are calculated as median values. Some data are from the GERM database. Early compilations for mineral–andesite partition coefficients are based upon phenocryst–matrix studies but are highly variable (Luhr and Carmichael, 1980; Gill, 1981). This is, in part, due to the range of melt compositions examined, the presence of mineral inclusions in the mineral separates analysed and the precision of the analytical methods used.

| Atomic number | Symbol | Name | Olivine | Orthopyroxene | Clinopyroxene | Garnet | Plagioclase | Hornblende |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Li | Lithium | 1.300 | 0.783 | nd | nd | 0.450 | 0.124 |

| 4 | Be | Beryllium | nd | 0.360 | nd | nd | 0.300 | nd |

| 19 | K | Potassium | nd | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.010 | nd | nd |

| 21 | Sc | Scandium | 0.283 | 3.875 | 14.000 | 3.900 | nd | 10.550 |

| 22 | Ti | Titanium | 0.030 | nd | nd | 2.620 | 0.047 | 2.320 |

| 23 | V | Vanadium | 0.080 | 1.000 | 3.150 | 8.000 | 0.270 | 9.650 |

| 24 | Cr | Chromium | 5.3–34 | 21–143 | 30–245 | 22.000 | (0.075) | 1.59–60.5 |

| 25 | Mn | Manganese | nd | 7.300 | 4.500 | nd | nd | 0.680 |

| 27 | Co | Cobalt | 1.885 | 12.000 | 5.500 | 1.800 | nd | 1.77–6.1 |

| 28 | Ni | Nickel | 20.800 | 0.79–24 | 4.6–9 | 0.600 | nd | 10.000 |

| 29 | Cu | Copper | 2.200 | 0.190 | 0.660 | nd | nd | 11.600 |

| 30 | Zn | Zinc | 1.500 | 3.500 | 2.000 | nd | nd | 0.42–8.7 |

| 31 | Ga | Gallium | 0.250 | 0.320 | 0.470 | nd | nd | nd |

| 37 | Rb | Rubidium | 0.036 | 0.022 | 0.030 | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.140 |

| 38 | Sr | Strontium | 0.020 | 0.005 | 0.280 | nd | 2.625 | 0.280 |

| 39 | Y | Yttrium | 0.045 | 0.343 | 2.000 | 11.000 | 0.024 | 2.500 |

| 40 | Zr | Zirconium | 0.010 | 0.031 | 0.290 | 0.530 | 0.001 | 0.260 |

| 41 | Nb | Niobium | 0.035 | 0.027 | 2.100 | 0.040 | 0.018 | 0.280 |

| 42 | Mo | Molybdenum | 0.111 | 1.323 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 55 | Cs | Caesium | 0.01–0.27 | 0.01–0.38 | 0.01–0.64 | nd | 0.038 | 0.01–0.5 |

| 56 | Ba | Barium | 0.020 | 0.115 | 0.068 | nd | 0.498 | 0.120 |

| 57 | La | Lanthanum | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.099 | 0.028 | 0.119 | 0.120 |

| 58 | Ce | Cerium | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.193 | 0.080 | 0.094 | 0.240 |

| 59 | Pr | Praseodymium | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.290 | 0.130 | 0.072 | 0.420 |

| 60 | Nd | Neodymium | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.420 | 0.222 | 0.065 | 0.630 |

| 62 | Sm | Samarium | 0.015 | 0.073 | 0.750 | 0.810 | 0.046 | 1.370 |

| 63 | Eu | Europium | 0.017 | 0.057 | 0.990 | 1.540 | 0.630 | 1.080 |

| 64 | Gd | Gadolinium | 0.016 | 0.140 | 0.910 | 4.590 | 0.040 | 1.490 |

| 65 | Tb | Terbium | 0.025 | 0.240 | 1.050 | 6.300 | 0.053 | 1.650 |

| 66 | Dy | Dysprosium | 0.031 | 0.260 | 1.200 | 9.000 | 0.025 | 1.770 |

| 67 | Ho | Holmium | 0.037 | 0.410 | 1.550 | 15.000 | 0.018 | 1.600 |

| 68 | Er | Erbium | 0.044 | 0.430 | 1.900 | 20.000 | 0.014 | 1.470 |

| 69 | Tm | Thulium | 0.071 | 0.645 | 1.400 | 22.000 | 0.012 | 1.300 |

| 70 | Yb | Ytterbium | 0.071 | 0.590 | 0.900 | 24.000 | 0.010 | 1.150 |

| 71 | Lu | Lutetium | 0.110 | 1.035 | 0.700 | 24.000 | 0.009 | 1.070 |

| 72 | Hf | Hafnium | 0.020 | 0.115 | 0.368 | 0.440 | nd | 0.430 |

| 73 | Ta | Tantallum | 0.065 | 0.049 | 0.430 | 0.080 | 0.069 | 0.270 |

| 82 | Pb | Lead | 0.014 | nd | 0.870 | nd | ≫ 0.012 | 0.120 |

| 90 | Th | Thorium | 0.039 | 0.010 | 0.100 | nd | > 0.012 | 0.017 |

| 92 | U | Uranium | 0.057 | 0.012 | nd | nd | 0.012 | 0.008 |

Notes: nd, no data; values in parentheses are uncertain.

REE partition coefficients for the major silicate minerals in andesitic melts.

The olivine partition coefficients reported in Table 4.2 are from a single andesite (experimental melt compositions 56–60 wt.% SiO2) in Dunn and Sen (1994); Be, B and Li are from Brenan et al. (1998); and other data are from the GERM database. Similarly, the orthopyroxene data represent three andesite samples (experimental melt compositions 56–61 wt.% SiO2) from Dunn and Sen (1994) and the GERM database. The clinopyroxene REE and HFSE data are calculated from Klein et al. (2000) for a hydrous tonalitic melt (SiO2 = 57.9 wt.%) at 900–1000°C and 1.5–3.0 GPa, Be, B and Li from Brenan et al. (1998) and the GERM database. As in the case of basaltic melts clinopyroxene REE partition coefficients are composition-dependant and vary according to the jadeite content of the pyroxene. Experimental studies show that garnet REE partition coefficients are strongly temperature-dependent with partition coefficients increasing with decreasing temperature Klein et al. (2000). For this reason, garnet REE and HFSE partition coefficients are taken from a single hydrous experiment in the study of Klein et al. (2000) in which the temperature is 950°C and pressure 1.5 GPa. The hornblende REE and HFS partition coefficients are from Klein et al. (1997) for a melt composition with 57.9 wt.% SiO2; other data are from Brenan et al. (1995) and the GERM database. The partition coefficient data for plagioclase are averages from the four andesitic compositions studied by Dunn and Sen (1994) and from the GERM database, although, as already discussed, partition coefficients for plagioclase are in part a function of the An content of the plagioclase.

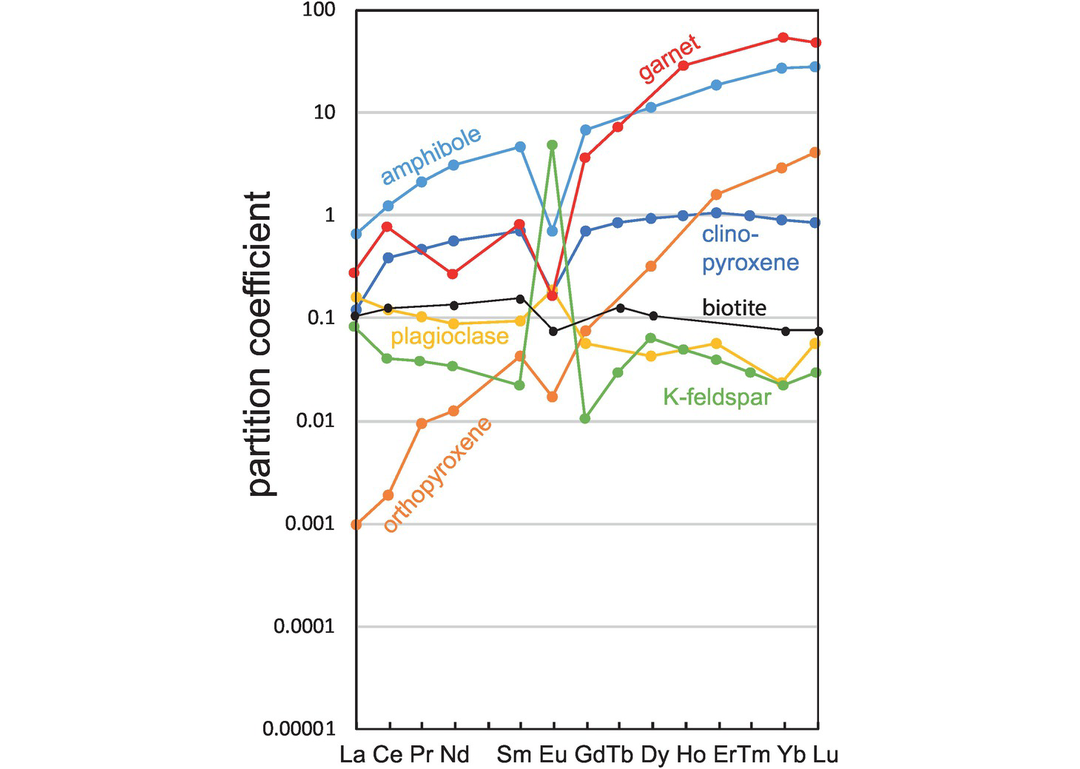

4.2.1.7 Partition Coefficients in Dacites and Rhyolites

Some indicative partition coefficients from published sources for the major rock-forming minerals in dacites, rhyodacites, rhyolites and high silica rhyolites are given in Table 4.3. These rocks have > 63 wt.%. SiO2 in the TAS classification. Compared with basaltic rocks, there are fewer modern experimental determinations of partition coefficient data for felsic rocks. Many published data sets are based upon phenocryst–matrix determinations and show some variability. In part this is because of the way partitioning behaviour is governed by melt structure and composition, but it also relates to other uncertainties with the matrix–phenocryst method discussed above. Data are drawn from a number of published sources supplemented with the compilations of Bacon and Druitt (1988) based upon rhyolites with 71 wt.% SiO2 and that of Nash and Crecraft (1985) for high-silica rhyolites (71–76 wt.% SiO2). The REE partition coefficients associated with some minerals common in felsic melts are shown in Figure 4.7.

REE partition coefficients for the major silicate minerals in felsic melts.

| Atomic number | Symbol | Name | Orthopyroxene | Clinopyroxene | Garnet | Plagioclase | Amphibole | K-feldspar | Biotite | Ilmenite | Magnetite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Li | Lithium | 0.076 | 0.260 | nd | 0.152 | 0.700 | ||||

| 19 | K | Potassium | 0.004 | 0.002 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 21 | Sc | Scandium | 7.100 | 15.900 | 20.200 | 0.010 | 11.790 | 0.027 | 4.9–20 | 5.9 | 5.000 |

| 22 | Ti | Titanium | 0.229 | 0.412 | 5.600 | 0.060 | nd | nd | nd | 150–235 | nd |

| 23 | V | Vanadium | nd | 7.440 | 7.000 | nd | 6.670 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 24 | Cr | Chromium | 10.000 | 30.000 | 3.850 | 0.100 | 40.000 | nd | 8.3–31 | 3.0000 | 30.000 |

| 25 | Mn | Manganese | 4.055 | 4.900 | nd | 0.060 | 3.890 | nd | 13.6–230 | 15–35 | 28–37 |

| 27 | Co | Cobalt | 38.000 | 17.000 | 3.000 | 0.150 | 37.000 | nd | nd | nd | 80.000 |

| 28 | Ni | Nickel | 11–25 | nd | nd | nd | 94.830 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 29 | Cu | Copper | nd | 0.110 | nd | 0.080 | 0.080 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 30 | Zn | Zinc | 6.000 | 1.960 | nd | 0.140 | 2.990 | nd | nd | 10.500 | 15.000 |

| 31 | Ga | Gallium | nd | 0.590 | nd | nd | 0.710 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 37 | Rb | Rubidium | nd | 0.030 | nd | 0.300 | 0.030 | 0.415 | 2.3–4.1 | nd | 0.010 |

| 38 | Sr | Strontium | 0.008 | 0.230 | 0.020 | 31.000 | 6.595 | 5.900 | 0.541 | nd | 0.010 |

| 39 | Y | Yttrium | 0.215 | 3.510 | 130.000 | 0.016 | 5.670 | nd | 1–1.4 | 0.2–1.6 | nd |

| 40 | Zr | Zirconium | 0.009 | 0.210 | 0.400 | 0.0002 | 0.450 | 0.195 | 1.3 | nd | 0.240 |

| 41 | Nb | Niobium | 0.002 | 0.210 | nd | 0.0025 | 1.400 | nd | 4–9.5 | 50.9–64.2 | nd |

| 42 | Mo | Molybdenum | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.030 | nd | 1.7–5.7 | 3.000 | 6–16 |

| 55 | Cs | Caesium | 0.010 | 0.023 | nd | 0.030 | 0.100 | 0.123 | 1.2–4.4 | nd | 0.010 |

| 56 | Ba | Barium | 0.0007 | 0.010 | nd | 0.200 | 0.200 | 14.450 | 18 | nd | 0.100 |

| 57 | La | Lanthanum | 0.001 | 0.130 | 0.278–0.54 | 0.170 | 0.710 | 0.085 | 0.76–15.1 | 7.100 | 0.660 |

| 58 | Ce | Cerium | 0.002 | 0.410 | 0.79–0.93 | 0.130 | 1.350 | 0.042 | 0.86–11 | 7.800 | 0.710 |

| 59 | Pr | Praseodymium | 0.010 | 0.500 | nd | 0.110 | 2.300 | 0.039 | nd | nd | nd |

| 60 | Nd | Neodymium | 0.013 | 0.600 | 0.27–0.73 | 0.094 | 3.280 | 0.035 | 0.9–5.7 | 7.600 | 0.930 |

| 62 | Sm | Samarium | 0.045 | 0.760 | 0.84–1.04 | 0.100 | 4.950 | 0.023 | 1–4.3 | 6.900 | 1.200 |

| 63 | Eu | Europium | 0.018 | 0.190 | 0.167–0.31 | 0.200 | 0.750 | 4.900 | 0.59–4.7 | 2.500 | 0.910 |

| 64 | Gd | Gadolinium | 0.080 | 0.760 | 3.7–5.3 | 0.060 | 7.400 | 0.011 | nd | nd | nd |

| 65 | Tb | Terbium | nd | 0.900 | 7.2–11.9 | nd | nd | 0.030 | 0.87–3.9 | 6.500 | 1.300 |

| 66 | Dy | Dysprosium | 0.345 | 1.000 | nd | 0.045 | 12.165 | 0.065 | 0.76–3.4 | 4.900 | 1.6–4.4 |

| 67 | Ho | Holmium | nd | 1.070 | 28.2–34.5 | nd | nd | 0.050 | nd | nd | nd |

| 68 | Er | Erbium | 1.700 | 1.150 | nd | 0.060 | 20.000 | 0.040 | nd | nd | nd |

| 69 | Tm | Thulium | nd | 1.050 | nd | nd | nd | 0.030 | nd | nd | nd |

| 70 | Yb | Ytterbium | 3.150 | 0.960 | 54–67 | 0.025 | 29.465 | 0.023 | 0.6–3 | 4.100 | 0.440 |

| 71 | Lu | Lutetium | 4.400 | 0.900 | 47–64 | 0.060 | 30.000 | 0.030 | 0.6–3.4 | 3.600 | 0.300 |

| 72 | Hf | Hafnium | 0.054 | 1.410 | nd | 0.050 | 0.855 | nd | 0.44–0.84 | 3.100 | 0.240 |

| 73 | Ta | Tantallum | 0.110 | 0.500 | nd | 0.030 | 0.430 | 0.011 | 1.2–1.9 | 64–85 | 1.200 |

| 82 | Pb | Lead | 0.018 | 0.020 | nd | 0.180 | nd | 1.825 | 0.1–1.6 | nd | nd |

| 90 | Th | Thorium | 0.140 | 0.100 | nd | 0.010 | 0.160 | 0.220 | 0.27–2 | 7.500 | 0.010 |

| 92 | U | Uranium | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.048 | 0.46–1.2 | 3.200 | 0.21–0.83 |

Notes: nd, no data

Plagioclase partition coefficients for Li, Sr, Y, Zr, Nb, Ba, Hf and the REE are from Brophy et al. (2011). In this study phenocrysts in equilibrium with a rhyolitic partial melt in gabbro (SiO2 = 72–73 wt.%) were analysed by ion microprobe. The partition coefficients reported are median values of multiple analyses. Data for the elements Ti, Mn, Zn, Cu and Pb are from the experimental study of Iveson et al. (2018) conducted at 810–860°C, 1.5–4.05 kb and oxygen fugacity NNO = −0.5 to +2 log units. Melt compositions have 73–75 wt.% SiO2 (dry) and the plagioclase is An39–59. Other values are from Bacon and Druitt (1988). It has already been noted that trace element partition coefficients for plagioclase are strongly dependent on the composition of the host mineral and on melt temperature (Sun et al., 2017). In particular, there is a strong relationship between the partition coefficients for Sr and Ba and the mole fraction of anorthite in plagioclase. Both elements are more compatible in albite than in anorthite (Blundy and Wood, 1991).

Partition coefficient data for K-feldspar are from the GERM database. REE values are based upon average values and the missing values estimated by interpolation. Partition coefficient data for more sodic alkali feldspars are given by Streck and Grunder (1997) for the trace elements Cr, Mn, Co, Rb, Sr, Cs, Ba, REE, Hf, Ta and Th and by Wolff and Ramos (2014) for Rb, Cs, Sr, Ba and Pb.

Trace element partition coefficients for clinopyroxene are taken from the experimental study of Huang et al. (2006) for Cs, La, Ce, Sm, Eu, Er and Yb, with the remaining REE interpolated. In this study the silica content of the melt was ca. 69 wt.%. Data for Li, Sc, V, Mn, Zn, Ga, Cu, Sr, Y, Zr, Nb, Ba, Hf and Pb are from the more siliceous melts in the experimental study of Iveson et al. (2018). K and Ti are from the Severs et al. (2009) phenocryst–melt inclusion data for dacitic melts (SiO2 = 65 wt.%). The remaining elements are from Bacon and Druitt (1988) and from the GERM database.

Partition coefficient data for orthopyroxene for Li, Sr, Y, Zr, Nb, Ba, Hf and REE are from Brophy et al. (2011), with data for K, Ti and Pb from Severs et al. (2009) and for Ni from Stimac and Hickmott (1994). Other trace elements are from Bacon and Druitt (1988). It should be noted that there is considerable variation in some published trace element partition coefficients between orthopyroxene and felsic melts – compare, for example, the REE in the compilation of Bacon and Druitt with the study of Brophy et al. (2011), where the differences between these two studies may reflect the different silica content of the melts.

Trace element partition coefficients for amphibole for Li, Sr, Y, Zr, Nb, Ba, Hf and the REE are from Brophy et al. (2011), and for the elements Sc, V, Mn, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ga, Rb, Mo and Pb from Iveson et al. (2018). There are some differences between these and other published data, in particular for Rb, Sr, Zr, Ba, Mo and Pb, and again it appears that small differences in melt composition may induce significant variations in partition coefficient values. Other data are from Bacon and Druitt (1988).

Garnet partition coefficient data are from the GERM database where the REE data are based upon the phenocryst–matrix data of Irving and Frey (1978). Biotite partition coefficients also from the GERM database and are mostly phenocryst–matrix measurements taken from Nash and Crecraft (1985). Partition coefficient data for magnetite are from the compilation of Nash and Crecraft (1985) and Bacon and Druitt (1988). Ilmenite data are from the GERM database with the REE from Nash and Crecraft (1985), and values for Ti, Mn, Y, Zr and Ta are from the study of Stimac and Hickmott (1994) in which the melt composition was ~75 wt.% SiO2.

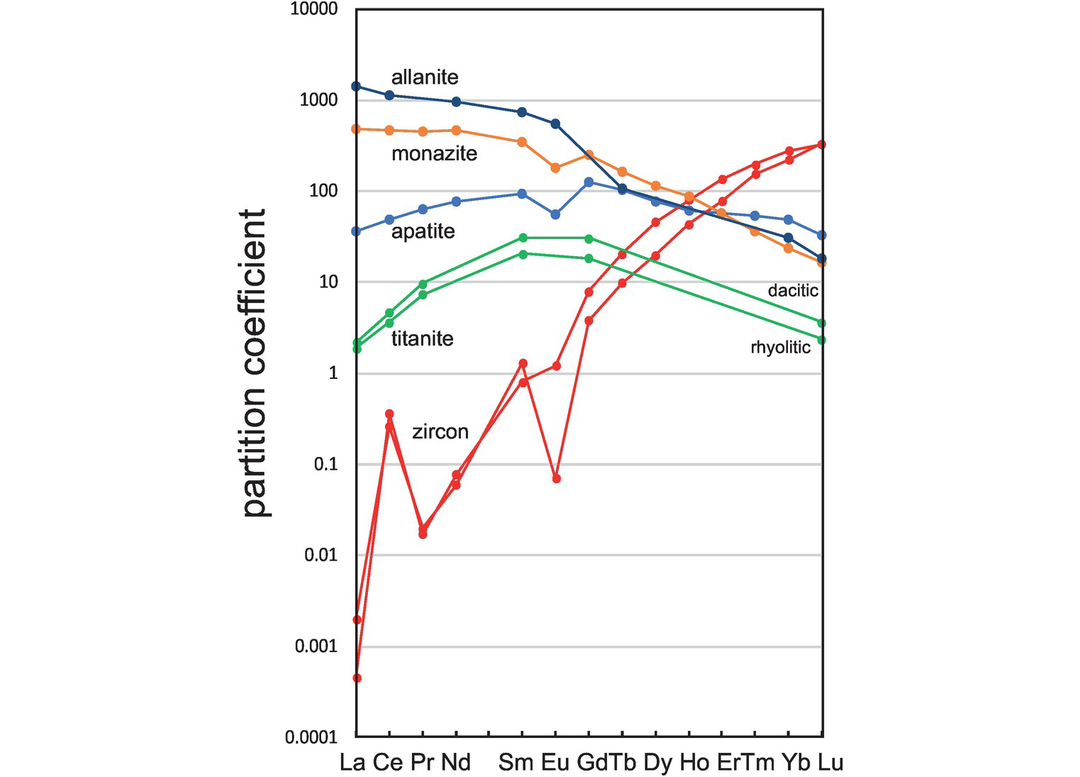

4.2.1.8 Partition Coefficients in Accessory Minerals

The minerals zircon, monazite, apatite, titanite and allanite occur primarily as accessory phases in felsic melts. These minerals occupy only a small volume of their parent rock but exercise a disproportionate effect on the distribution of some trace elements, in particular the REE. Further, they contain elements which are normally regarded as trace elements, but in these particular phases form a stoichiometric component of the host mineral. This means that they do not obey Henry’s law (Section 4.2.1) and therefore do not behave in the same way as other trace elements (Prowatke and Klemme, 2006; Chapman et al., 2016).

The appearance of an accessory phase in a melt is governed by the solubility of the phase in the melt. For example, in the case of zircon (ZrSiO4) the crystallisation of the mineral from a melt is governed by the solubility of Zr in the melt, such that when the melt is saturated in Zr, zircon will crystallise from the melt. In practice, therefore, zircon (and other accessory minerals) will appear in an igneous sequence towards the end of a differentiation process. Zr solubility is controlled by variables such as melt composition and temperature. Formulations of accessory mineral solubility have been given by Kelsey et al. (2008) for zircon and monazite, by Stepanov et al. (2012) for monazite, and by Harrison and Watson (1984) for apatite.

In this section the main focus is on the partition coefficients for the REE and for element pairs such as Nb–Ta and Th–U where either large partition coefficients or, in the case of element pairs, very different partition coefficients between the pair may have a major impact on the trace element composition of the melt. Partition coefficients for other elements derived from older mineral–matrix measurements are given in the GERM database. Relevant values are summarised in Table 4.4 and a plot of partition coefficients for the REE in accessory phases is given in Figure 4.8.

Partition coefficients for the REE in accessory minerals in felsic rocks (data from Table 4.4). Note the difference in scale from Figures 4.5–4.7.

Zircon (ZrSiO4) is one of the best studied accessory minerals because of its importance in geochronology and its use, when found as detrital grains in sediment, for recovering information about ancient continental crust. Hanchar and van Westrenen (2007) review the REE partition coefficient data for zircon and show that many of the published values in the older literature determined using phenocryst–matrix methods do not conform to the lattice strain model and are probably in error. This is particularly true for the incompatible light REE. They recommend the values of Sano et al. (2002) for zircon in equilibrium with a dacitic melt, and these are given in Table 4.4. A more recent study by Chapman et al. (2016) calculated trace element partition coefficients for a suite of bulk rock compositions from the Coast Mountains Batholith in British Columbia with SiO2 = 51–76 wt.%. The median values calculated for this suite are given in Table 4.4. An accurate measure of REE partition coefficients in zircon is particularly important when the partition coefficient data are inverted to estimate the parental melt composition as in the case of detrital zircons whose origin is unknown. The Chapman et al. (2016) partition coefficients seem robust in this respect. Trace element data for Y and Nb are from Chapman et al. (2016) and for B, Ti, Rb, Sr and Ba from Thomas et al. (2002). Ti concentrations in zircon may be used as a geothermometer (Watson et al., 2006) although Schiller and Finger (2019) give a more recent evaluation of the applicability of this methodology.

| Atomic number | Symbol | Name | Zircon | Apatite | Monazite | Titanite | Allanite | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | 1 | 2, 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7, 8 | 7, 8 | ||||||

| range | median | Dacite | Rhyolite | range | median | |||||||||||

| 3 | Li | Lithium | nd | nd | nd | 0.005 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||||

| 5 | B | Boron | nd | 0.017 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||||

| 22 | Ti | Titanium | nd | 3.150 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.94–4.03 | 2.675 | ||||

| 37 | Rb | Rubidium | nd | 0.006 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.00026 | 0.00033 | nd | nd | ||||

| 38 | Sr | Strontium | nd | 0.034 | nd | 24.000 | nd | nd | 0.62 | 0.44 | nd | nd | ||||

| 39 | Y | Yttrium | nd | 47.000 | nd | 24.000 | 20–606 | 78.500 | 14.3 | 8.96 | nd | nd | ||||

| 40 | Zr | Zirconium | nd | nd | nd | 0.012 | nd | nd | 3.78 | 3.48 | nd | nd | ||||

| 41 | Nb | Niobium | nd | 0.150 | nd | 0.009 | nd | nd | 7.26 | 5.44 | nd | nd | ||||

| 55 | Cs | Caesium | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.0023 | 0.0022 | nd | nd | ||||

| 56 | Ba | Barium | nd | 0.004 | nd | 0.010 | nd | nd | 0.0025 | 0.0029 | nd | nd | ||||

| 57 | La | Lanthanum | 0.00046 | 0.002 | 36.0 | 24.0 | 74–3240 | 485.0 | 2.17 | 1.88 | 775–2819 | 1399 | ||||

| 58 | Ce | Cerium | 0.360 | 0.260 | 48.0 | 47.0 | 66–3011 | 459.5 | 4.6 | 3.61 | 628–2245 | 1120 | ||||

| 59 | Pr | Praseodymium | 0.017 | 0.020 | 64.0 | 34.0 | 71–3194 | 446.0 | 9.7 | 7.39 | nd | nd | ||||

| 60 | Nd | Neodymium | 0.077 | 0.060 | 77.0 | 36.0 | 73–3125 | 463.0 | nd | nd | 538–1980 | 970 | ||||

| 62 | Sm | Samarium | 0.800 | 1.300 | 93.0 | 42.0 | 56–2526 | 344.0 | 31.2 | 20.4 | 272–1254 | 728 | ||||

| 63 | Eu | Europium | 1.220 | 0.070 | 55.0 | 8.0 | 12–1759 | 177.5 | nd | nd | 138–794 | 549 | ||||

| 64 | Gd | Gadolinium | 8.000 | 3.800 | 127.0 | 45.0 | 49–1920 | 252.0 | 30.5 | 18.2 | nd | nd | ||||

| 65 | Tb | Terbium | 20.700 | 9.900 | 102.0 | nd | 34–1400 | 163.5 | nd | nd | 107–139 | 108 | ||||

| 66 | Dy | Dysprosium | 45.900 | 20.000 | 76.0 | 46.0 | 27–1015 | 115.5 | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||||

| 67 | Ho | Holmium | 80.000 | 44.000 | 62.0 | nd | 20–709 | 86.5 | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||||

| 68 | Er | Erbium | 136.000 | 77.000 | 57.0 | 88.0 | 16–534 | 57.5 | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||||

| 69 | Tm | Thulium | 197.000 | 154.000 | 53.0 | nd | 12–324 | 36.0 | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||||

| 70 | Yb | Ytterbium | 277.000 | 219.000 | 48.0 | 95.0 | 10–237 | 23.5 | nd | nd | 19–36 | 31 | ||||

| 71 | Lu | Lutetium | 325.000 | 331.000 | 33.0 | 91.0 | 8–187 | 16.5 | 3.65 | 2.38 | 12–23 | 18 | ||||

| 72 | Hf | Hafnium | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 6.9 | 4.9 | nd | nd | ||||

| 73 | Ta | Tantallum | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 84 | 54.8 | nd | nd | ||||

| 82 | Pb | Lead | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.87 | 0.750000 | nd | nd | ||||

| 90 | Th | Thorium | nd | nd | nd | nd | 86–3853 | 691.000 | 0.14 | 0.101000 | 416–1331 | 732 | ||||

| 92 | U | Uranium | nd | nd | nd | nd | 9–377 | 60.000 | 0.07 | 0.090000 | 22–97 | 53 | ||||

Partition coefficient data for the REE in apatite (Ca5(PO4)3(F, Cl, OH)) given in Table 4.4 are from the ion microprobe study of Sano et al. (2002) for apatite in equilibrium with a dacitic melt and from Brophy et al. (2011) for apatite in contact with natural interstitial rhyolitic (71–76% SiO2) glass. Median values are given for the Brophy et al. (2011) REE partition coefficients, for these show a wide range of measured values and are higher than the Sano et al. (2002) data for the heavy REE.

Monazite ((LREE)PO4) is a light REE phosphate, xenotime mirror monazite ((Y,HREE)PO4) is its rarer heavy REE counterpart, and these phases are important in controlling REE concentrations during the melting and fractionation of crustal rocks. Stepanov et al. (2012) present partition coefficient data for Y, REE, Th and U in monazite. These partition coefficients were experimentally determined over a temperature range of 750–1200°C and a pressure range of 1–5 GPa on a hydrous Fe-, Mg-free peraluminous granitic melt with 76–78 wt.% SiO2. Partition coefficient values vary by over an order of magnitude, and the ratio of D-values for heavy to light REE increases with temperature and decreases with the water content of the melt. For this reason, the range of experimentally determined values and a median value are given in Table 4.4.

Selected trace element partition coefficients have been experimentally determined for titanite (sphene, CaTiSiO5) by Prowatke and Klemme (2005), who show that partition coefficients are strongly dependent upon melt composition. For this reason, values for both dacite (SiO2 = 64.3 wt.%) and rhyolite (SiO2 = 69.8 wt.%) are given in Table 4.4.

Klimm et al. (2008) give partition coefficients for allanite, a REE-rich member of the epidote group (Ca, (REE)Al2Fe2+(Si2O7)(SiO4)O(OH)), in felsic melts with between 71 and 74 wt.% SiO2 produced during the water-saturated melting of basalt. Their results for La, Ce, Nd, Sm and Eu, given as a range in Table 4.4, show that the partition coefficients are strongly temperature-dependant and decrease from 900 to 800°C. Partition coefficients for Tb, Yb and Lu are from Chesner and Ettlinger (1989).

4.2.2 Geological Controls on the Distribution of Trace Elements

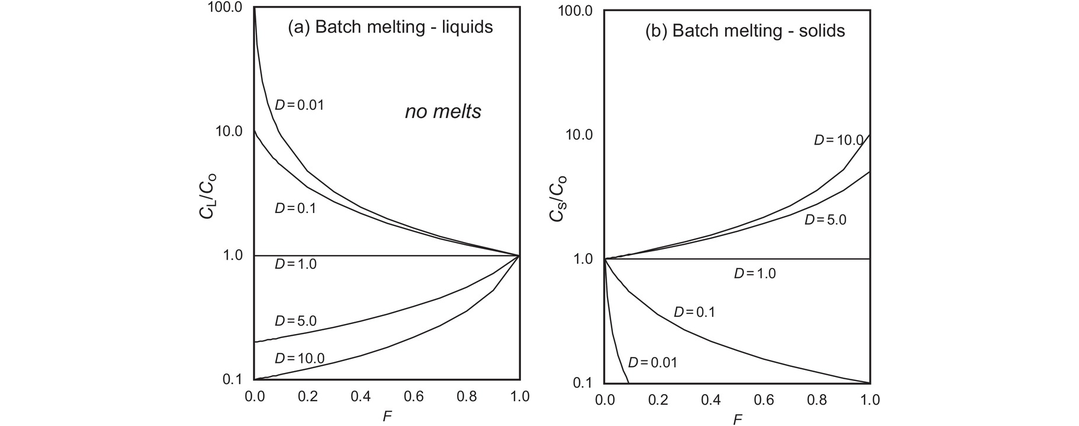

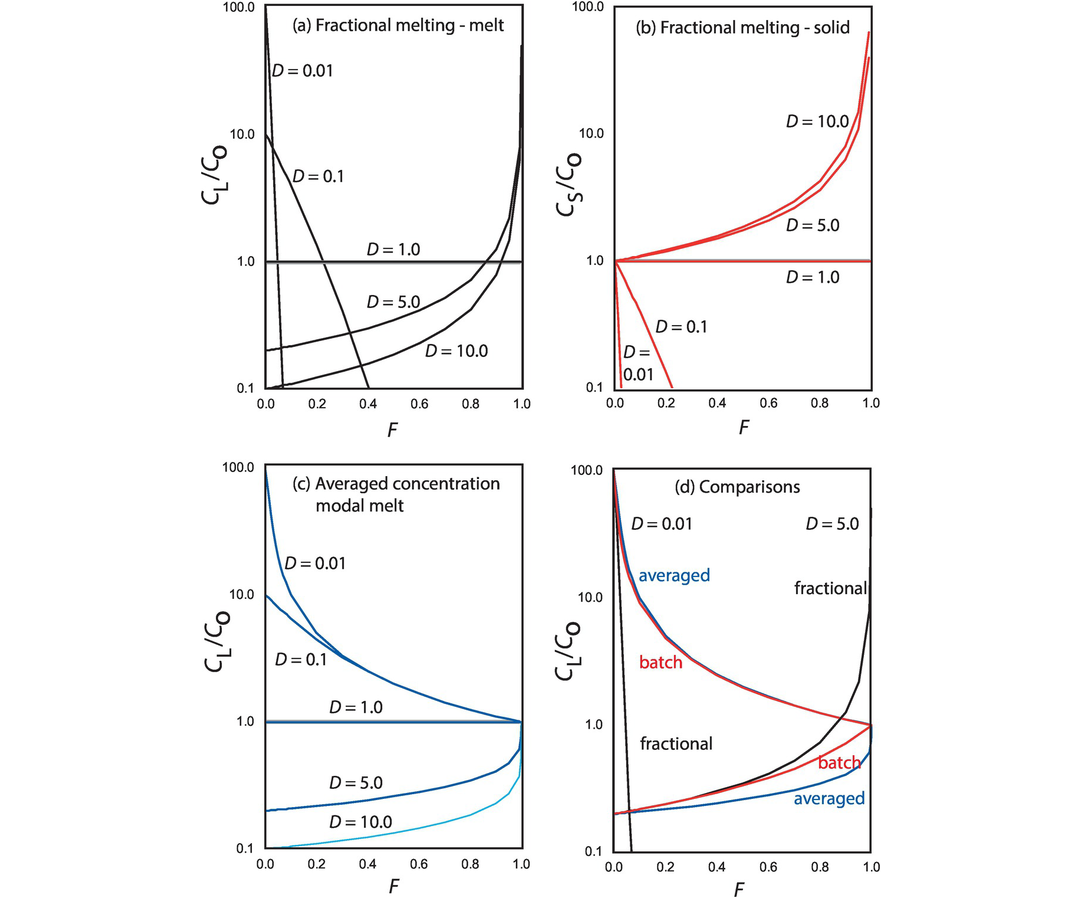

The geochemical study of trace elements is a powerful tool for understanding and recognising geological processes. Our knowledge of the partitioning of trace elements between minerals and their parental melt means that a range of geological processes in which minerals are in equilibrium with a melt can be modelled. Further, inverting the modelling means that processes operating in a particular magmatic system may be identified. In contrast to magmatic systems, however, our knowledge of the behaviour of trace elements in aqueous and sedimentary systems is less amenable to quantification, and the main focus of this discussion is therefore upon magmatic systems. In this section we consider a range of geological processes for which there are quantitative models to describe the behaviour of trace elements. The relevant equations are given and the terms used are defined (Table 4.5). The interested reader will find a full derivation of the relevant equations in the text by Shaw (2006).

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| CA | Concentration of a trace element in the wall rock being assimilated during AFC processes |

| CL | Weight concentration of a trace element in the liquid |

| Average weight concentration of a trace element in a mixed melt |

| CO | In partial melting the weight concentration of a trace element in the original unmelted solid; in fractional crystallisation the weight concentration in the parental liquid |

| Ck | Weight concentration of a trace element in the residual solid during crystal fractionation |

| CS | Weight concentration of a trace element in the residual solid (after melt extraction) |

| SSCB | Weight concentration of a trace element in a steady state liquid after a large number of RTF cycles |

| DO | Bulk distribution coefficient of the original solids |

| Dl | Mineral-melt partition coefficient, or the bulk distribution coefficient of the fractionating assemblage, during crystal fractionation |

| DS | Strain-free partition coefficient in the lattice strain model |

| DRS | Bulk distribution coefficient of the residual solids |

| F | Weight fraction of melt produced in partial melting; in fractional crystallisation the fraction of melt remaining |

| f | Fraction of melt allocated to the solidification zone in in situ crystallisation which is returned to the magma chamber |

| f' | A function of F, the fraction of melt remaining in AFC processes |

| ML | Mass of the liquid remaining during in situ crystallisation |

| MO | Total mass of the magma chamber in in situ crystallisation |

| n | Number of rock volumes processed during zone refining |

| P | Bulk distribution coefficient of minerals which contribute to a melt |

| r | Ratio of the assimilation rate to the fractionation rate in AFC processes |

| x | In an RTF magma chamber, the mass fraction of the liquid crystallised in each RTF cycle; during in situ crystallisation, the proportion of trapped melt in the magma chamber |

| y | Mass fraction of the liquid escaping in each RTF cycle |

4.2.2.1 Element Mobility