6.1 Introduction

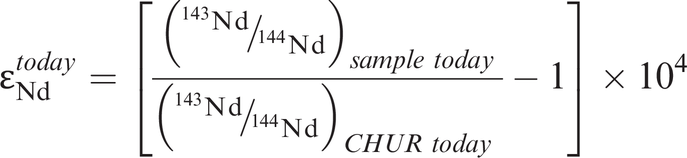

Radiogenic isotopes are used in geochemistry in two principal ways: (i) to determine the age of rocks and minerals and (ii) to identify geological processes and sources. The former application is geochronology, while the latter is known as isotope geology or isotope geochemistry. There are some excellent texts which deal with these disciplines (e.g., Rink and Thompson, 2015; White, 2015; Reiners et al., 2018) and the reader is referred to these for more detailed treatments of the topics introduced here.

In the first part of this chapter the main principles of geochronology are briefly described and the interpretation of geochronological results reviewed. The second half of the chapter describes the use of radiogenic isotopes in petrogenesis, an exciting and rapidly evolving field. The use of radiogenic isotopes as tracers of petrogenetic processes has allowed geochemists to sample the deep interior of the Earth, previously the sole domain of geophysicists. The results of such studies have led to important geochemical constraints on the nature of the continental crust and the Earth’s mantle, which can be combined with our physical knowledge of these domains to help provide a unified chemical-physical model of the deep Earth.

6.2 Radiogenic Isotopes in Geochronology

The foundations of modern geochronology were laid at the turn of the century in the work of Rutherford and Soddy (1903) on natural radioactivity. They showed that the process of radioactive decay is exponential and independent of chemical or physical conditions. Thus, rates of radioactive decay may be used for measuring geological time. The isotopic systems used in age calculations are listed in Table 6.1 and Box 6.1. In this section we discuss two of the most common techniques used in geochronological calculations: isochron diagrams and model age calculations. This is followed by a discussion of the significance of the calculated ages.

| Technique | Decay scheme | Decay constant λ (yr−1) | Reference | Isochron plot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x-axis | y-axis | ||||

| Rb–Sr | 87Rb → 87Sr + β | 1.42 × 10−11 | 1a | 87Rb/86Sr | 87Sr/86Sr |

| Sm–Nd | 147Sm → 143Nd + He | 6.54 × 10−12 | 2 | 147Sm/143Nd | 143Nd/143Nd |

| Lu–Hf | 176Lu → 176Hf + β | 1.867 × 10−11 | 3b | 176Lu/177Hf | 176Hf/177Hf |

| Re–Osc | 187Re → 187Os + β | 1.666 × 10−11 | 4 | 187Re/188Os | 187Os/188Os |

| 187Re (ppb) | 187Os (ppb) | ||||

| K–Ar | 40K → 40Ar − β | 0.581 × 10−10 | 1d | 40K/36Ar | 40Ar/36Ar |

| 39Ar/36Ar | 40Ar/36Ar | ||||

| K–Cac | 40K → 40Ca + β | 4.962 × 10−10 | 1, 5 | 40K/42Ca | 40Ca/42Ca |

| K total | 5.543 × 10−10 | 1 | |||

| La–Cec | 138La → 138Ce + β | 2.37 × 10−12 | 6 | 138La/136Ce | 138Ce/136Ce |

| La–Bac | 138La → 138Ba − β | 4.44 × 10−12 | 7 | 138La/137Ba | 138Ba/137Ba |

a Officially accepted value today, but other values exist and may be in use (1.393 × 10−11; Nebel et al., 2011). Older data use λ87Rb = 1.39 ×10−11 and can be recalculated for the modern decay constant using a correction factor (e.g., 1.39/1.42).

b Older data use λ176Lu = 1.94 × 10−12 (DePaolo, 1988) or 1.96 × 10−12 (Patchett and Tatsumoto, 1980).

c Specialist techniques carried out in only a few laboratories.

References: 1, Steiger and Jager (1977); 2, Lugmair and Marti (1978); 3, Söderlund et al. (2004); 4, Smoliar et al. (1996); 5, Marshall and DePaolo (1982); 6, Tanimizu (2000); 7, Sato and Hirose (1981).

(a) Decay constants (Steiger and Jager, 1977)

238U » 206Pb 1.55125 × 10−10 yr−1 (λ1)

235U » 207Pb 9.8485 × 10−10 yr−1 (λ2)

232Th » 208Pb 4.9475 × 10−11 yr−1 (λ3)

(b) Isotope ratios of primeval lead (represented by Canyon Diablo troilite of Tatsumoto et al., 1973)

(206Pb/ 204Pb) = 9.307

(207Pb/ 204Pb) = 10.294

(208Pb/ 204Pb) = 29.476

(c) Age of the Earth derived from the meteoritic isochron (Tatsumoto et al., 1973; Tilton, 1973)

207Pb/ 204Pb versus 206Pb/ 204Pb yields an isochron with a slope = 0.626208 and an age for the Earth of 4.57 Ga.

(d) Present day ratio 238U/ 235U = 137.88

(e) Symbols used in U–Th–Pb isotope geochemistry

μ = 238U/204Pb, κ = 232Th/238U

(f) Ratios used for plotting the U–Pb concordia curve

| Age (Ga) | 206Pb/238U | 207Pb/235U |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 |

| 0.4 | 0.06402 | 0.48281 |

| 1.0 | 0.16780 | 1.67741 |

| 1.4 | 0.24256 | 2.97009 |

| 1.8 | 0.32210 | 4.88690 |

| 2.2 | 0.40674 | 7.72917 |

| 2.6 | 0.49679 | 11.94371 |

| 3.0 | 0.59261 | 18.19308 |

| 3.4 | 0.69456 | 27.45973 |

| 3.6 | 0.74796 | 33.65562 |

| 3.8 | 0.80304 | 41.20041 |

| 4.0 | 0.85986 | 50.38776 |

| 4.2 | 0.91846 | 61.57526 |

| 4.4 | 0.97892 | 75.19836 |

| 4.6 | 1.04128 | 91.78732 |

6.2.1 Isochron Calculations

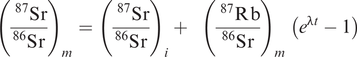

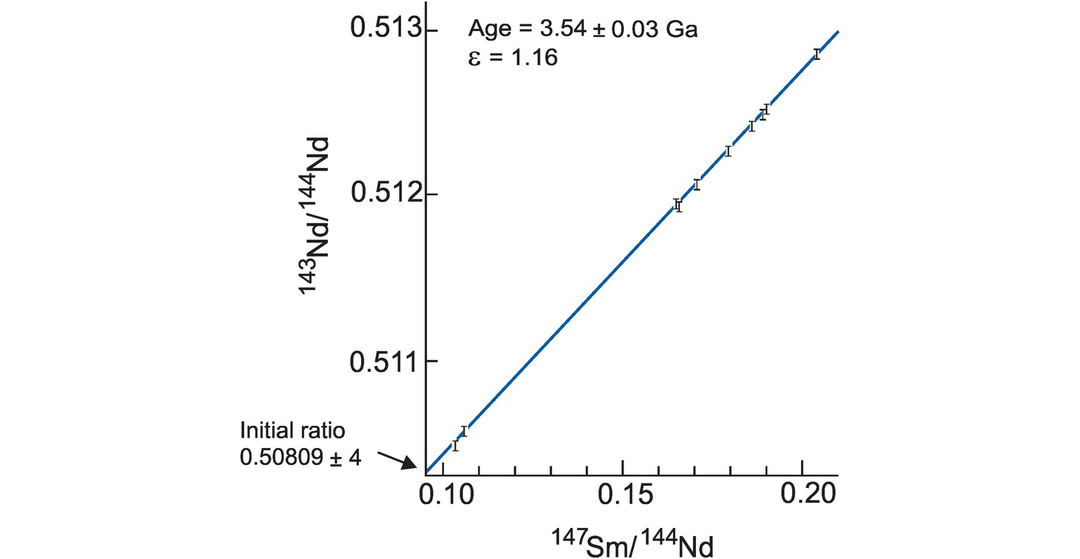

An isochron diagram is a bivariate plot of measured parent–daughter isotope ratios for a suite of cogenetic samples or for a mineral suite from a single sample. When the sample suite defines a linear array, this is said to be an isochron, and the slope of the line is proportional to the age of the sample suite. Consider, for example, the Rb–Sr system where the total number of 87Sr atoms in a rock which has been a closed system for t years is given by the equation:

87Srm is the total number of atoms of 87Sr present today, 87Sri is the number of atoms of 87Sr initially present when the sample first formed, 87Rbm is the number of atoms of 87Rb present (measured) today, and λ (lambda) is the radioactive decay constant (Table 6.1). The precise measurement of absolute isotope concentrations is difficult, so instead isotope ratios are normally determined. An isotope not involved in the radioactive decay scheme is used as the denominator. In the case of the Rb–Sr isotope system this isotope is 86Sr and Eq. 6.1 is rewritten as:

The ratios (87Sr/86Sr)m and (87Rb/86Sr)m are measured by mass spectrometry, leaving the initial ratio (87Sr/86Sr)i and the age of the rock (t) as unknowns. Since Eq. 6.2 is the equation of a straight line, the age and intercept can be calculated from a plot of measured (87Sr/86Sr)m and (87Rb/86Sr)m for a suite of cogenetic samples. This methodology is illustrated in Figure 6.1. The age is calculated from the slope of the line using the equation

where t is the age and λ is the decay constant. Time is measured from the present and is expressed as either Ma (106 years) or Ga (109 years). The intercept on the (87Sr/86Sr) axis is equal to the initial ratio (87Sr/86Sr)i, a parameter of considerable petrogenetic importance and discussed more fully later in this chapter.

Schematic isochron diagram. A suite of igneous rocks (a–c) form at t = 0 from the same batch of magma which subsequently differentiated. They evolve over 500 Ma and 1000 Ma. At t = 0 each member of the rock suite has the same initial ratio (87Sr/86Sr)i but because the magma suite is chemically differentiated, each rock has a different concentration of Rb and Sr, and therefore a different 87Rb/86Sr ratio. Each sample plots as a separate point on the 87Rb/86Sr versus 87Sr/86Sr isochron diagram. From t = 0 to t = 500 Ma or t = 1000 Ma, individual samples evolve along a straight line with a slope of −1 (e.g., a–a′–a′′) reflecting the decay of a single atom of 87Rb to a single atom of 87Sr. In practise the resulting change in 87Sr/86Sr is small and the vertical scale is normally exaggerated so the path taken by these points will be closer to a vertical line. The amount of 87Sr produced in a given sample is proportional to the amount of 87Rb present. The slope of each isochron (t = 500 Ma, t = 1000 Ma) is proportional to the age of the sample suite. The intercept on 87Sr/86Sr is the initial ratio.

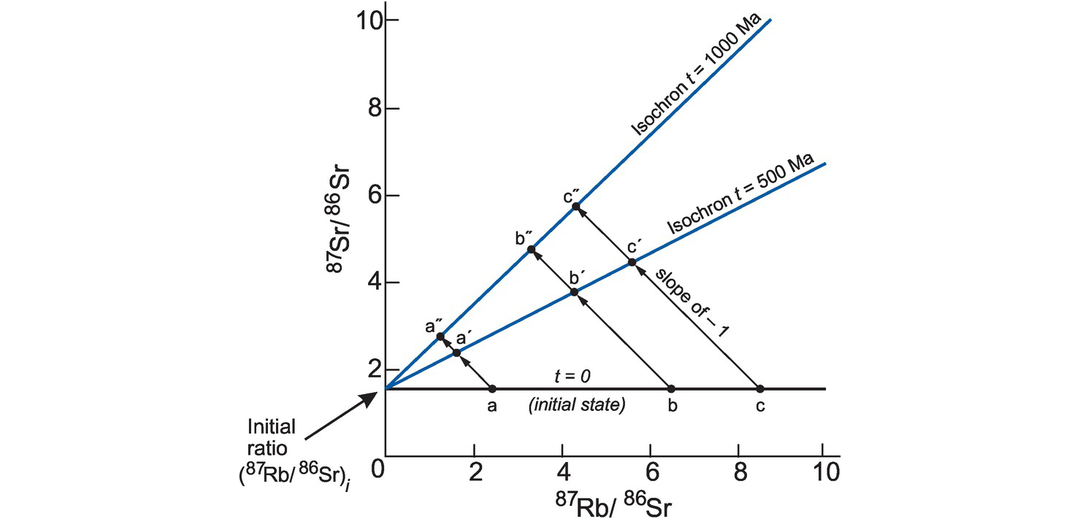

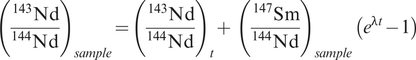

Thus, an isochron calculation requires a suite of cogenetic samples formed from the same parental material – this may be a suite of whole rock samples from a single pluton or a suite of different minerals from a single sample. The isochron calculation assumes that there has been no exchange of parent–daughter isotopes other than through radioactive decay. An example of a Sm–Nd isochron derived from a suite of related volcanic rocks using the data in Table 6.2 is shown in Figure 6.2.

| Sample | Rock type | 147Sm/144Ndb | 143Nd/144Nd |

|---|---|---|---|

| (± 2σ error) | |||

| HSS-74 | Sodic porphyry | 0.1030 | 0.510487 ± 36 |

| HSS-161 | Acid tuff | 0.1054 | 0.510570 ± 32 |

| HSS-52B | Felsic pillow lava | 0.1653 | 0.511950 ± 22 |

| HSS-56 | Basaltic lava | 0.2040 | 0.512875 ± 32 |

| R-14 | Basaltic komatiite | 0.1888 | 0.512504 ± 34 |

| HSS-32 | Basaltic komatiite | 0.1649 | 0.511957 ± 22 |

| HSS-88A | Peridotitic komatiite | 0.1792 | 0.512292 ± 34 |

| HSS-92 | Peridotitic komatiite | 0.1858 | 0.512439 ± 34 |

| HSS-95 | Peridotitic komatiite | 0.1902 | 0.512541 ± 28 |

| HSS-523 | Peridotitic komatiite | 0.1701 | 0.512084 ± 20 |

a Hamilton et al. (1979b); data used to construct Figure 6.2.

b 147Sm/144Nd determined to a precision of 0.2% at the 2σ level.

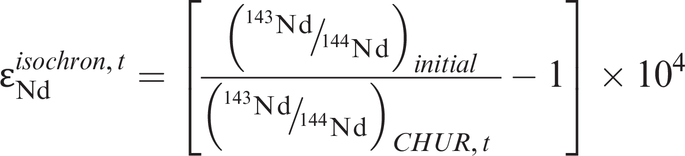

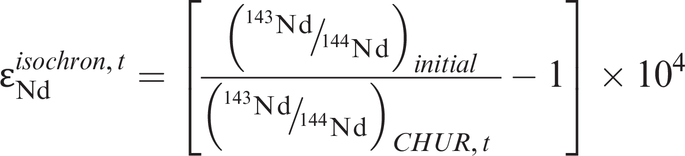

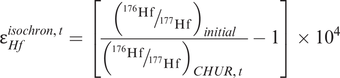

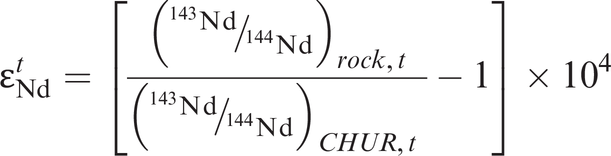

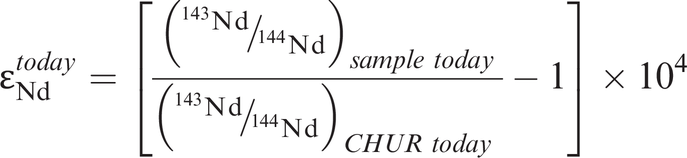

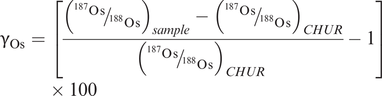

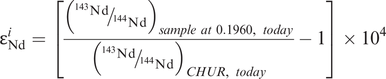

A Sm–Nd isochron. An isochron plot of 147Sm/144Nd and 143Nd/144Nd for volcanic rocks from the Onverwacht group, South Africa (after Hamilton et al. (1979b)). The data are given in Table 6.2. Error bars for 143Nd/144Nd are 2σ (errors on 147Sm/144Nd are too small to show). The slope of the best fit line is proportional to the age or the suite (3.54 ± 0.03 G(a); the intercept of this line on the 143Nd/144Nd axis where 147Sm/144Nd = 0 is the initial 143Nd/144Nd ratio (0.50809 ± 0.00004). The εNd value (+1.16) is a measure of the difference between the initial ratio and a chondritic model for the Earth’s mantle at 3.54 Ga expressed in parts per 10,000 (see Section 6.3.4 and Box 6.2). The positive value for εNd indicates that the volcanic rocks were derived from a (slightly) depleted mantle source at 3.54 Ga, although there are large errors on this estimate.

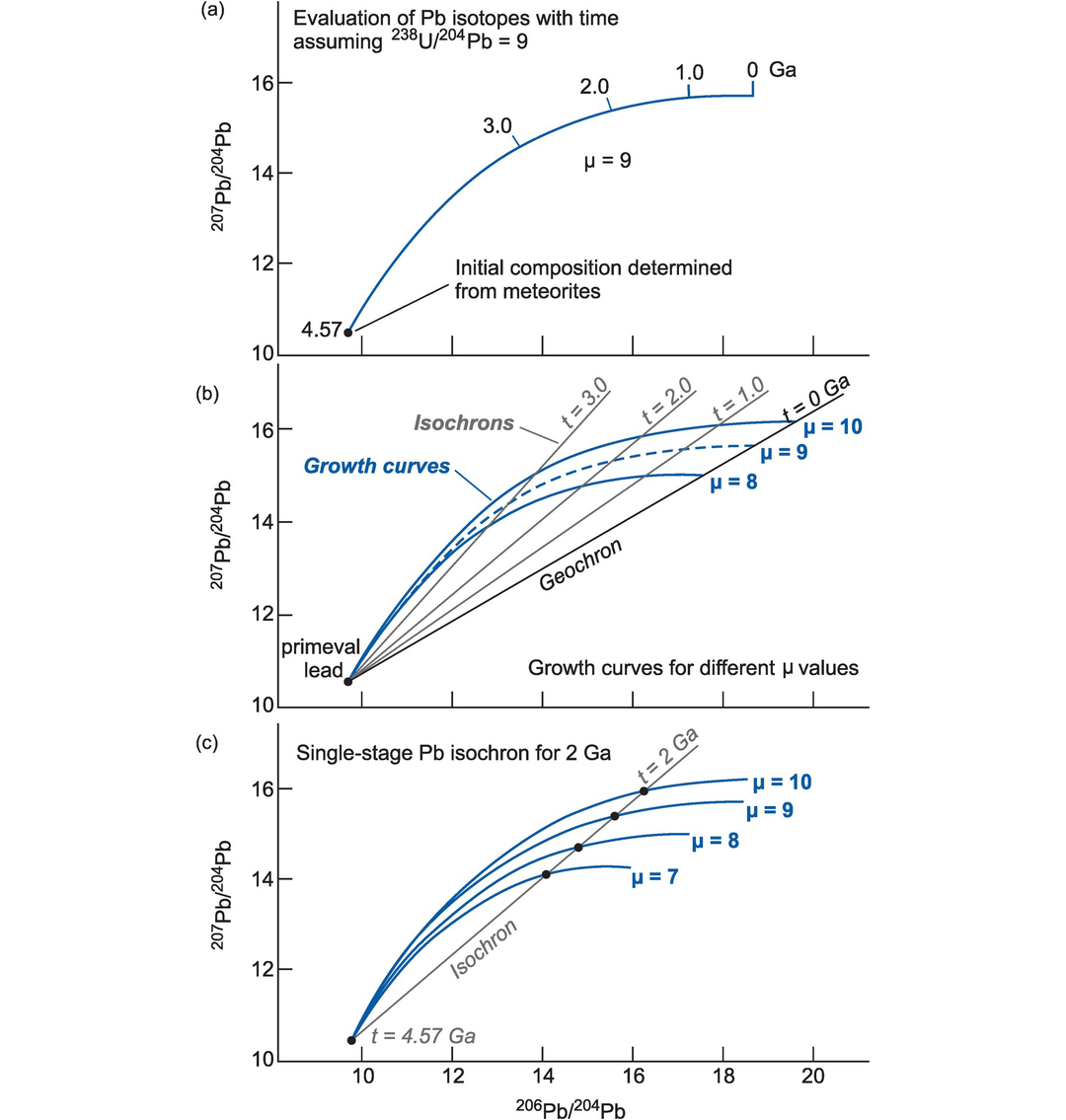

6.2.1.1 Pb Isotope Isochrons

A Pb–Pb whole rock isochron is constructed by plotting the isotope ratios 206Pb/204Pb on the x-axis and 207Pb/204Pb on the y-axis. However, the interpretation of a linear array on this diagram is more complicated than for the Rb–Sr system because 206Pb and 207Pb are the products of separate radioactive decay schemes with different rates of decay (Box 6.1). In this case the isochron equation and must be solved iteratively (see Harmer and Eglington, 1987); see Section 6.2.5.3.

6.2.1.2 Fitting an Isochron

A simple but approximate method to fit an isochron is to draw a best-fit straight line by eye through the plotted points. Provided a suitable scale is chosen, both the slope of the line and the intercept can be determined with reasonable accuracy and these may be used to make preliminary estimates of the age and initial ratio. Precise results are obtained from statistical line-fitting procedures which estimate the slope and intercept of the isochron. These normally use a version of weighted least squares regression (see Section 2.5) and standard equations can be found in Excel, IsoplotR (Vermeesch, 2018b), and other statistical packages.

An important aspect of isochron regression is the realistic estimate of the uncertainty associated with the age and initial ratios. A measure of the ‘goodness of fit’ of an isochron is the mean squares of weighted deviates (MSWD). This is a measure of the fit of the line to the data within the limits of analytical error. Ideally, an isochron should have a MSWD of ≤ 1; anything greater than this implies that the scatter in the data points cannot be explained solely by experimental error. However, Brooks et al. (1972) suggest that this value be restricted to isochrons involving infinitely large numbers of samples, whereas for more typical datasets higher values up to ~2.5 may be acceptable.

6.2.1.3 Errorchrons

The origin of the scatter on an isochron is one of the most important interpretive aspects of geochronology. If the scatter results in a MSWD of ≤2.5, it is deemed analytical. If the MSWD is >2.5, it is geological. Brooks et al. (1972) proposed the term ‘errorchron’ for the situation where a straight line cannot be fit to a suite of samples within the limits of analytical error. An errorchron by definition implies that the scatter of the data is a consequence of geological error and indicates that one or more of the initial assumptions of the isochron has not been fulfilled, that is, that the samples are not cogenetic or that there has been subsequent parent–daughter isotopic exchange.

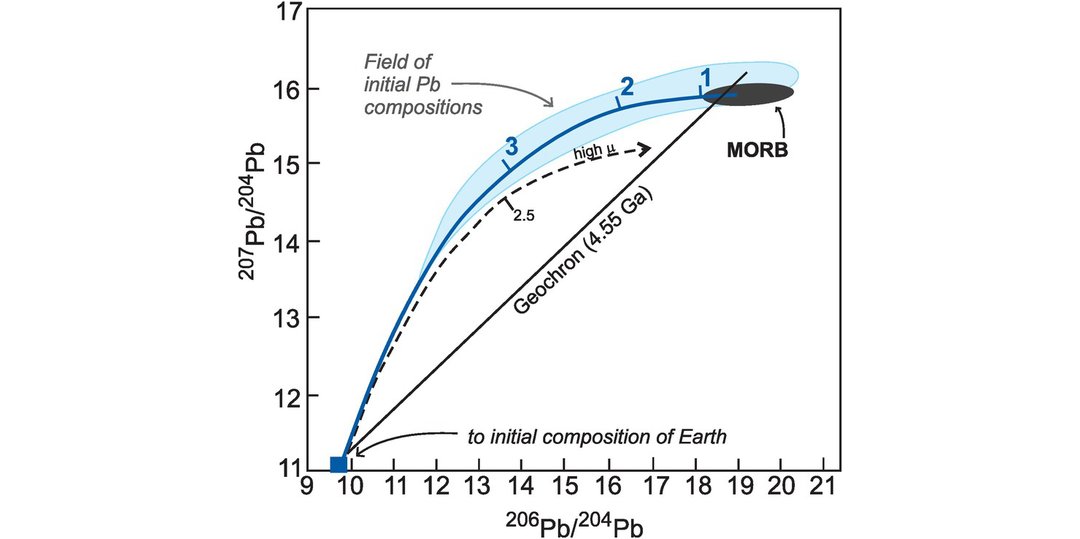

6.2.1.4 The Geochron

The geochron represents an isochron drawn at t = 0 and uses the composition of the appropriate isotope ratio at the time the Earth formed, that is, the Earth’s primordial isotopic composition. In principle, a geochron can be defined for any isotopic system, although in practice it is most commonly used in the interpretation of lead isotopes and is used as a reference line in some lead isotope studies. The lead isotope geochron (constructed as in Section 6.2.1.1) is calculated using the initial values for the Earth given in Box 6.1(b) for ages between 4.4 and 4.6 Ga. Its precise position is a function of the presumed age of the Earth, and so although a geochron represents a zero age isochron, the age of the Earth used in its computation (say, 4.57 Ga) must also be specified.

6.2.2 Model Ages

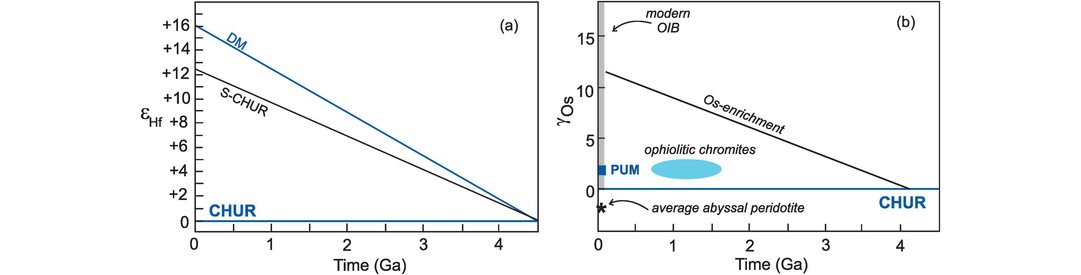

A model age is a measure of the length of time a sample has been separated from the mantle from which it was originally derived. Model ages are most commonly quoted for the Sm–Nd and Lu–Hf systems and can be calculated for an individual rock from a single pair of parent–daughter isotopic ratios. They must, however, be interpreted with care as the basis of all model age calculations requires an assumption about the isotopic composition of the mantle source region from which the samples were originally derived which may or may not be correct. There are two frequently quoted models for such mantle reservoirs, CHUR (the chondritic uniform reservoir) and depleted mantle (DM).

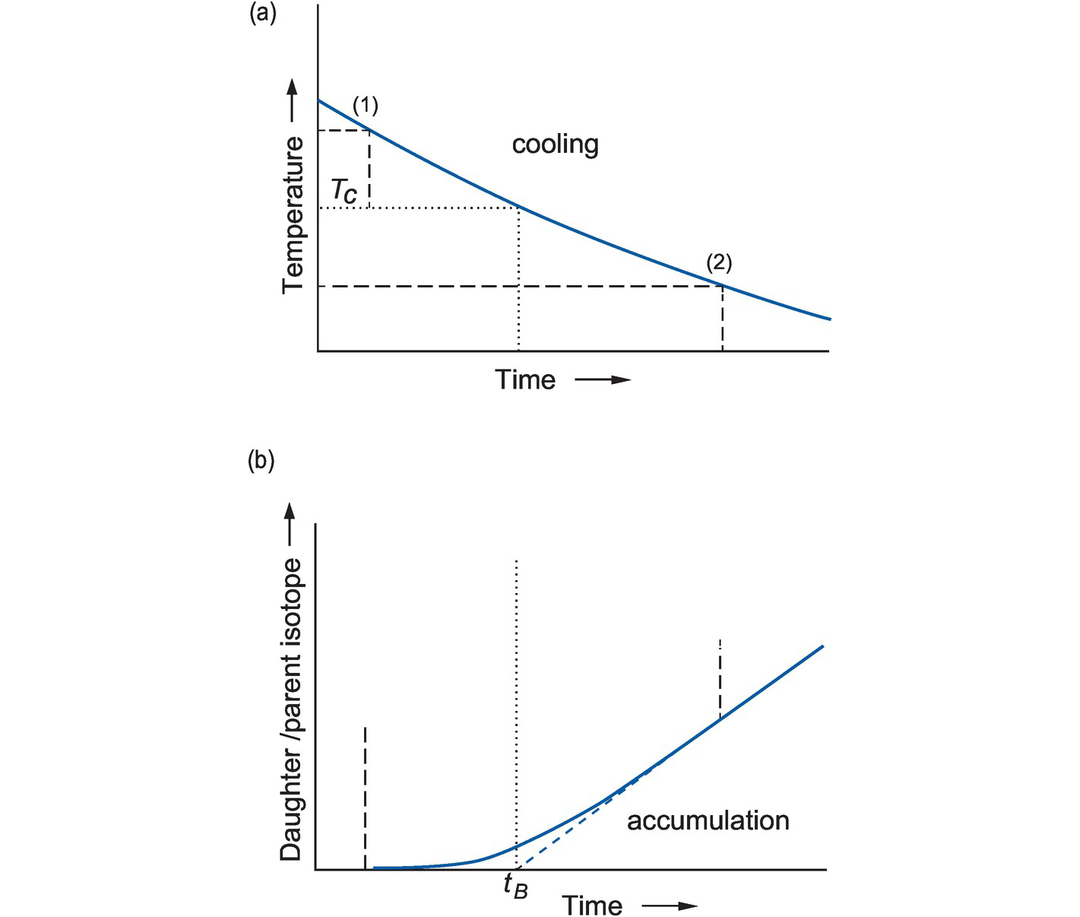

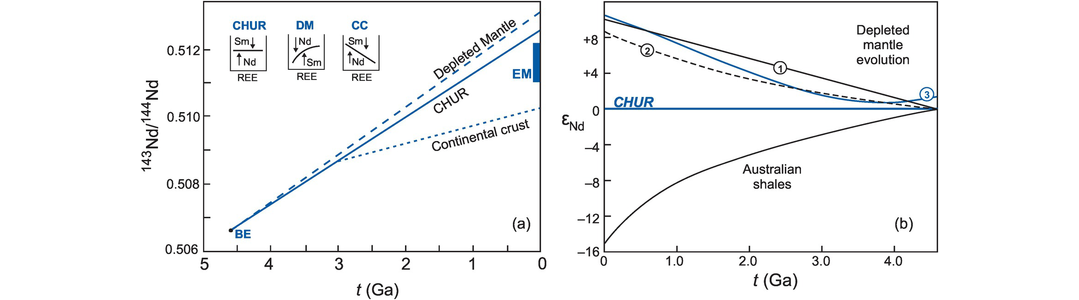

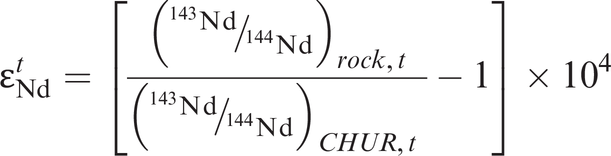

6.2.2.1 CHUR Model Ages

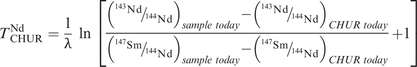

The CHUR model (sometimes referred to as T-CHUR) assumes that when the Earth was formed at 4.6 Ga, the Earth’s primitive mantle had the same isotopic composition as the average chondritic meteorite. For neodymium isotopes CHUR is synonymous with the composition of the bulk Earth. A model age calculated relative to CHUR, therefore, is the time in the past at which the sample suite separated from the CHUR mantle reservoir and acquired a different Sm/Nd ratio. It is also the time at which the sample had the same isotopic composition as CHUR. This is illustrated in Figure 6.3a in which the present-day 143Nd/144Nd composition of the sample is extrapolated back in time until it intersects the CHUR evolution line and gives the CHUR model age. The evolution curve for the sample is constructed from the present-day values for 147Sm/144Nd and 143Nd/144Nd for that sample and at some time (t) in the past (143Nd/144Nd)t is calculated from the equation

where λ is the decay constant, t is an arbitrarily selected time in the past to construct the evolution curve, and 147Sm/144Nd is the present-day ratio in the sample. Alternatively, a CHUR model age is calculated from the present-day 147Sm/144Nd and 143Nd/144Nd of a single sample using the equation

where λ is the decay constant for 147Sm to 143Nd (Table 6.1). Both the preferred and historical values used to calculate CHUR are given in Table 6.3b. Care must be taken in selecting which CHUR value to use because different values have been reported in the past and if data are to be compared, they need to be normalized to the same CHUR values. Model ages are also sensitive to the difference in Sm/Nd between the sample and CHUR, and only fractionated samples with Sm/Nd ratios which are sufficiently different from the chondritic value will yield precise model ages.

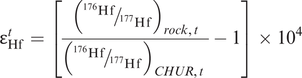

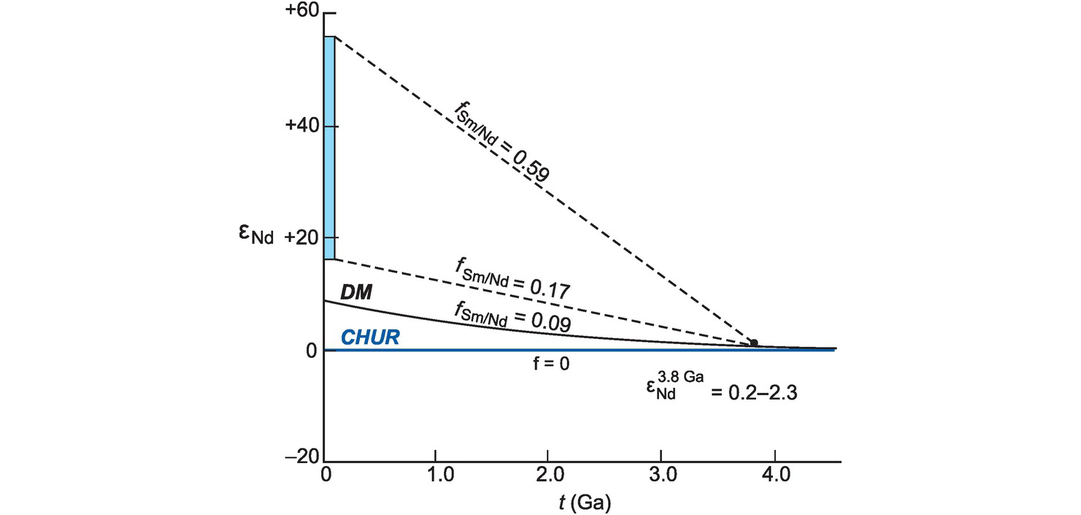

The calculation of Nd and Hf model ages. (a) The evolution of 143Nd/144Nd over time for sample 234 (Table 6.4) compared with two models of the mantle: CHUR (the chondritic uniform reservoir) and DM (the depleted mantle). A Nd model age is the time at which the sample had the same 143Nd/144Nd ratio as its mantle source. In this case there are two possible solutions depending upon the preferred mantle model. The TCHUR model age is approximately 1.67 Ga and the TDM model age is approximately 1.98 Ga. A similar diagram can be constructed using the epsilon notation (Section 6.3.4) in place of 143Nd/144Nd. (b) The evolution of 176Hf/177Hf expressed in εHf units (see Section 6.3.4) versus time. The Hf model age is the time at which the sample had the same 176Hf/177Hf ratio as its depleted mantle source. In this example the whole-rock 176Hf/177Hf measured today (εHf = −15) is extrapolated back through time until it intersects the model mantle composition of interest, providing the model age (THfCHUR = 1.15 Ga; THfDM = 1.85 Ga). (c) The evolution of εHf versus time and Hf-in-zircon model ages (modified from Kemp and Hawkesworth, 2014; with permission from Elsevier). Three different scenarios are shown for a zircon crystallised from a melt at 500 Ma with an εHf = −5. (i) The zircon crystallised from a melt that was derived from older mafic crust producing THfDM = 2.5 Ga; (ii) the melt was derived from an older felsic continental crust producing THfDM = 2.0 Ga; (iii) the melt was derived from a mixture of juvenile mantle melt and melt extracted from a heterogeneous Archean crust (dashed arrow) – in this case the model age has no significance. Also note the variation in depleted mantle composition as recorded by MORB (εHf = +8 to +22) compared with the assumed DM model composition. In the absence of other constraints, all scenarios can generate significantly different model ages.

| DMb | BSEb | CHURc | S-CHURd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 87Rb/86Sr | 0.085 | 0.061 | ||

| 87Sr/86Sr | 0.7026 | 0.7045 | 0.7047 | 0.7030 |

| Rb (ppm) | 600 | 430 | ||

| 147Sm/144Nd | 0.1960 | 0.2082 | ||

| 143Nd/144Nd | 0.51311 | 0.512634 | 0.512630 | 0.512990 |

| 176Lu/177Hf | 0.0336 | 0.0375 | ||

| 176Hf/177Hf | 0.28330 | 0.282843 | 0.282785 | 0.28313 |

| 187Re/188Os | 0.40186 | |||

| 187Os/188Os | 0.1276e |

| Nd isotopes | DePaolo; Wasserburgb | O'Nions; Allegre; Hawkesworthb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normalising factors | ||||||||

| = 0.636151 [1], = 0.63613 [2] |  | = 0.63223 [3] | |||||

| = 0.2096 [1], = 0.209627 [4] |  | = 0.7219 [3] | |||||

| Chondritic Uniform Reservoir | ||||||||

| = 0.505829 [1] | Sm/Nd = 0.31 [5] = 0.50677 ? 10 [6] | ||||||

| = 0.511847 [4], = 0.511836 [7] | = 0.51262 [8] | ||||||

| = 0.1967 [1] | = 0.1966 [9], = 0.1967 [10], = 0.19637-0.1968 [11] | ||||||

| Depleted mantle | ||||||||

| = 0.51235 [7], = 0.512245 [12] | = 0.51315 [10], = 0.51316 [9] | ||||||

| = 0.513114 [13], = 0.51317-0.51330 [11] | ||||||||

| = 0.214 [7], = 0.217 [14] = 0.225 [15], = 0.23 [12] | = 0.2137 [10], = 0.222 [13], = 0.233-0.251 [11] | ||||||

| International rock standard BCR-1 | ||||||||

| = 0.51184 [16] | = 0.512669 ± 8 [17] | ||||||

| Basaltic achondrite best initial (BABI) | ||||||||

| 87Sr/86Sr(4.6 Ga) | = 0.6998 [18] | |||||||

a Assuming λ = 6.54 × 10−12 yr−1.

b References: [1] Jacobsen and Wasserburg (1980); [2] DePaolo (1981a); [3] O’Nions et al. (1977); [4]Wasserburg et al. (1981); [5] O’Nions et al. (1979); [6] Lugmair et al. (1975); [7] McCulloch and Black (1984); [8] Hawkesworth and van Calsteren (1984); [9] Goldstein et al. (1984); [10] Peucat et al. (1988); [11] Allegre et al. (1983); [12] McCulloch and Chappell (1982); [13] Michard et al. (1985); [14] Taylor and McLennan (1985); [15] McCulloch et al. (1983); [16] DePaolo and Wasserburg (1976); [17] Hooker et al. (1981); [18] Hans et al. (2013).

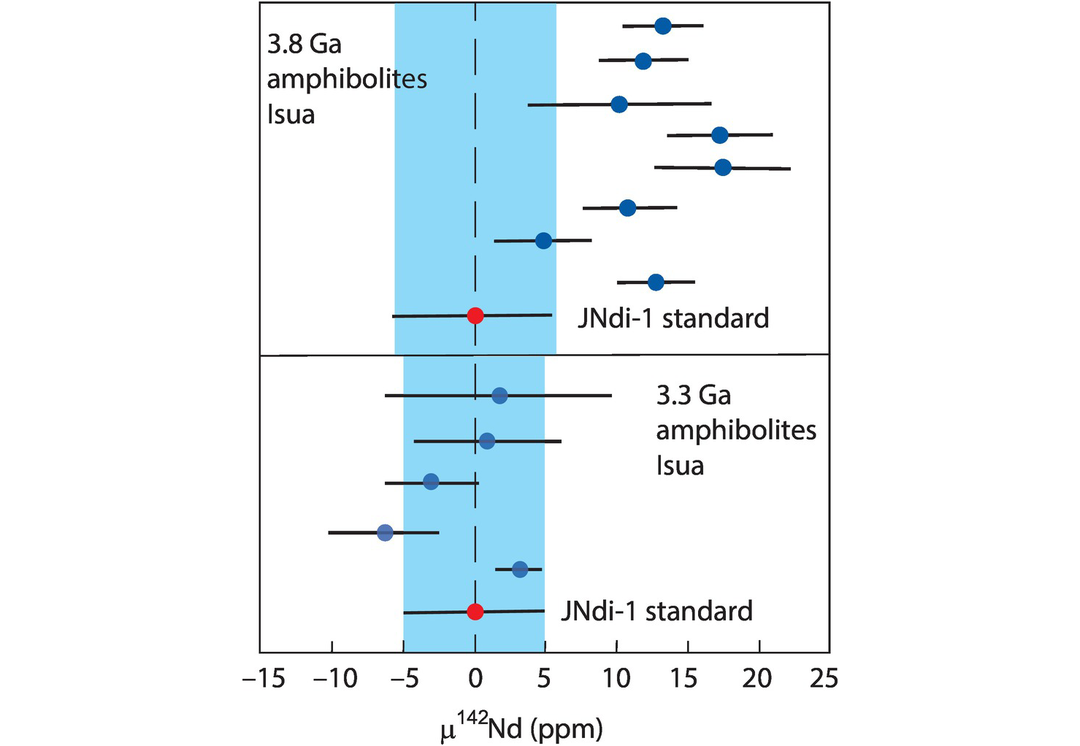

Currently, there is some debate over whether the Earth’s mantle had a chondritic or a supra-chondritic (S-CHUR) composition. Caro and Bourdon (2010) provide an overview of the arguments in favour of S-CHUR and from studies of the short-lived Nd isotope 142Nd argue that the non-chondritic 142Nd/144Nd of the Earth implies a non-chondritic Sm/Nd for the Earth. Their S-CHUR values are given in Table 6.3a, and S-CHUR model ages can be determined in the same way as TCHUR by simple substitution of S-CHUR values for CHUR values. It should also be noted, however, that the Earth’s mantle could have had a chondritic Sm/Nd but that this compositional component was sequestered at the base of mantle early in Earth’s history – in which case the CHUR model remains applicable.

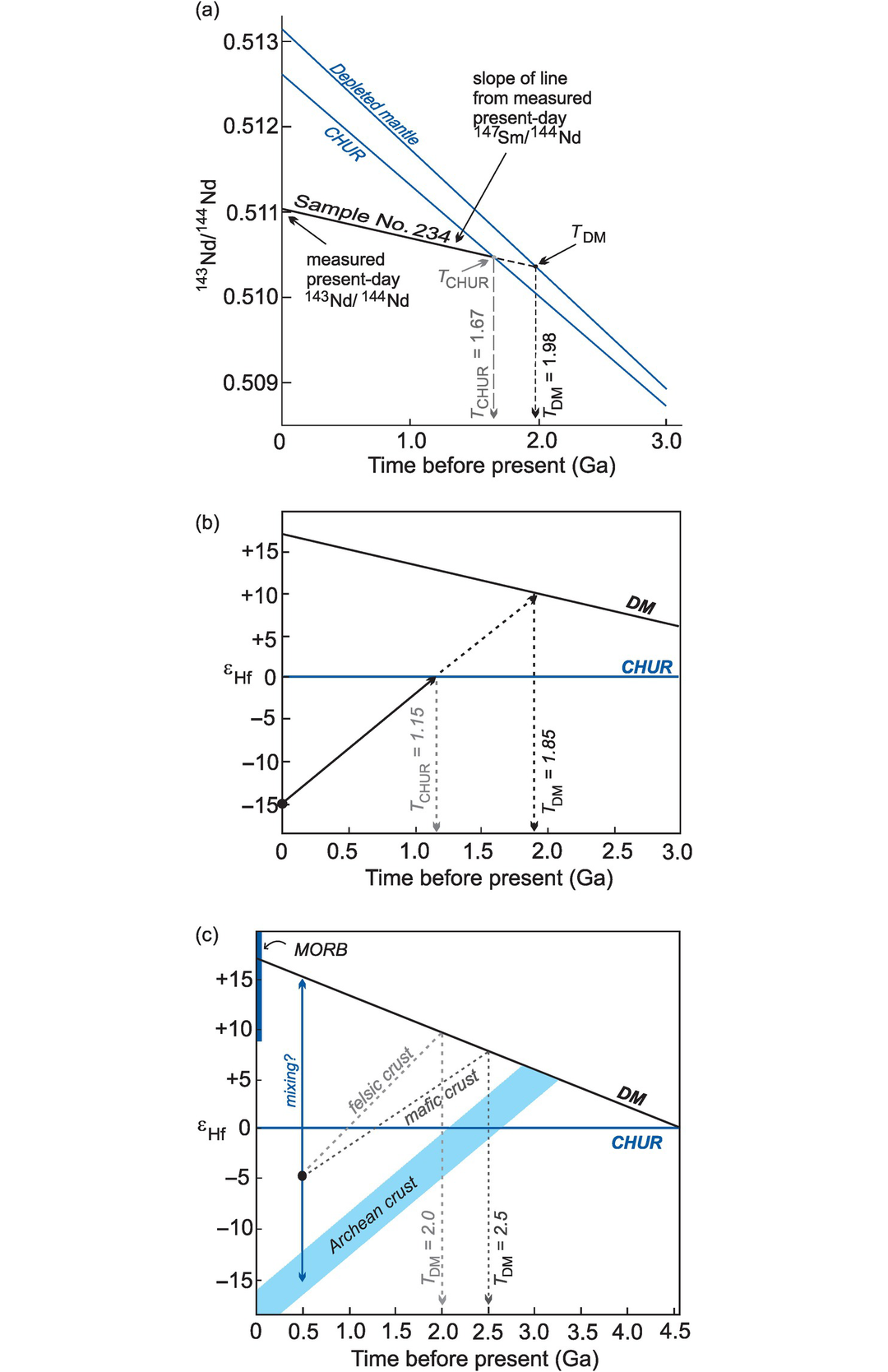

The calculation of model ages for the Lu–Hf isotopic system uses the same principles as the Sm–Nd system. The Lu–Hf system also involves relatively insoluble, immobile and refractory elements (Lu, Hf), and therefore the Lu/Hf of Earth is also expected to be similar to chondrite. The evolution curve for a sample is constructed from the present-day (measured) values of 176Lu/177Hf and 176Hf/177Hf for the sample, calculated at some time (t) using the equation:

where λ is the decay constant for 176Lu to 176Hf, t is an arbitrarily selected time in the past to construct the evolution curve, and the subscript ‘sample’ denotes the measured, present-day ratio of the sample. The CHUR model age is calculated from the present-day 176Lu/177Hf and 176Hf/177Hf of a sample using the equation:

where λ is the decay constant for 176Lu to 176Hf (Table 6.1). This is illustrated in Figure 6.3b in which the present-day 176Hf/177Hf composition of the sample is extrapolated back in time until it intersects the CHUR evolution line, providing the CHUR model age. The values for CHUR are given in Table 6.1. In Figure 6.3b the Hf isotope values are expressed in εHf units – this is an alternative way of expressing an isotope ratio relative to CHUR. The ε notation is frequently applied to both Hf and Nd isotopes and is discussed more fully in Section 6.3.4. As in the case of Nd isotope model ages, when compiling data it is necessary to check that all the data are normalized to the same CHUR value.

6.2.2.2 Depleted Mantle Model Ages (TDM)

Studies of initial 143Nd/144Nd (often denoted with the subscript i) from Precambrian terrains suggest that the mantle which generated the continental crust has evolved since earliest times with a Sm/Nd ratio greater than that of CHUR. Consequently, model ages for the continental crust are usually calculated with reference to the depleted mantle (DM) reservoir rather than CHUR. Depleted mantle model ages are calculated by substituting the values for (143Nd/144Nd)CHUR today with (143Nd/144Nd)DM today and (147Sm/144Nd)CHURtoday with (147Sm/144Nd)DMtoday into Eq. 6.5. Similarly, Hf depleted mantle model ages are calculated by substituting the appropriate DM values into Eq. 6.7 such that (176Hf/177Hf)CHURtoday and (176Lu/177Hf)CHURtoday become (176Hf/177Hf)DMtoday and (176Lu/177Hf)DMtoday. The appropriate values are given in Table 6.3 and a graphical solution of a TDM model age calculation for both the Nd and Hf systems (using the epsilon notation – see Section 6.3.4) is illustrated Figure 6.3a, b.

6.2.2.3 Hf Depleted Mantle Model Ages Calculated for Zircon

Hf model ages (or crustal residence ages; see Section 6.2.3.2) can also be calculated for the mineral zircon and are used to trace crustal evolution – see, for example, Kemp and Hawkesworth (2014) for an excellent overview. Zircon has a very low Lu/Hf (<0.002) and therefore a low in-growth of radiogenic 176Hf and so preserves the near-initial 176Hf/177Hf inherited from its source at the time it crystallised. For the simplest scenario, that of an igneous zircon with a U–Pb crystallisation age the same as its Hf model age, the U–Pb age directly dates the time at which the host melt was extracted from its (depleted) mantle reservoir. These ages therefore reflect the timing of the formation of new crust, although it is important to note that there is some uncertainty over the 176Hf/177Hf of the depleted mantle (Chauvel and Blichert-Toft, 2001).

However, in contrast to the simple scenario outlined above, many zircon U–Pb ages are significantly younger than their THfDM ages and may differ by several hundred million years (Figure 6.3c). In this case, the interpretation of Hf model ages can be much more ambiguous. This uncertainty arises because zircon sequesters Hf more strongly than Lu, and so the Lu/Hf in zircon is not easily converted into Lu/Hf of the parent magma. Further, as shown in the εHf versus time plot in Figure 6.3c, the mixing between a magma and a melt derived from source rocks containing zircons of different ages will provide a calculated model age without geological significance. There is also a range of possible DM growth curves which will affect both Nd and Hf model ages. These are discussed more fully in Section 6.3.3.

6.2.2.4 Assumptions in the Calculation of Model Ages

When calculating a model age it is important to ensure that the assumptions on which the calculation is based are fulfilled. The first major assumption is that of the composition of the isotopic reservoir which is being sampled, for this could be S-CHUR, CHUR or DM. This is important because there can be as much as 300 Ma difference between TCHUR and TDM Nd model ages as illustrated in Figure 6.3a. A further concern is that there are several different models for the depleted mantle source. Three of these are illustrated in Figure 6.14b below using the εNd notation (the deviation of the isotopic composition from CHUR) and it is important therefore that the model being used for the depleted mantle is specified. There are also a number of different normalisation schemes in use for the Nd isotope system. These are listed in Table 6.3b. It is important therefore that when calculating model ages or plotting data from different sources the same set of normalising values is used consistently.

A second major assumption used in model age calculations is that the parent/daughter element ratio of the sample has not been modified by fractionation after its separation from the mantle source. A third assumption is that all material is extracted from the mantle was derived in a single event. Examples of Nd–model age calculations using Eq. 6.5 for TNdCHUR and TNdDM for a suite of metamorphic rocks from central Australia are given in Table 6.4.

| Sample no. |  |  | TNdCHUR (Ga) | TNdDM (Ga) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mafic granulites | ||||

| 226 | 0.1853 | 0.511772 ± 36 | 0.856 | 2.203 |

| 234 | 0.1251 | 0.511049 ± 30 | 1.672 | 1.975 |

| 551 | 0.2134 | 0.512122 ± 36 | 2.596 | 2.950 |

| 868 | 0.2046 | 0.512013 ± 24 | 3.388 | 2.491 |

| Quartzofeldspathic and calc-silicate rocks | ||||

| 501A | 0.1248 | 0.511006 ± 28 | 1.755 | 2.034 |

| 507 | 0.1310 | 0.511039 ± 24 | 1.844 | 2.115 |

| 503 | 0.1248 | 0.510967 ± 32 | 1.837 | 2.093 |

| 512 | 0.1150 | 0.510794 ± 32 | 1.938 | 2.145 |

6.2.3 Important Concepts in Geochronology

6.2.3.1 Closure Temperature (Tc)

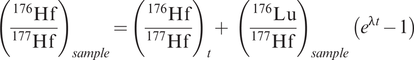

One of the principal controls on the retention of a radiogenic daughter product in a mineral is temperature, and so it is important to know the point at which a rock or mineral becomes a closed system with respect to retention of a particular daughter isotope. This temperature is known as the closure or blocking temperature (Tc) (Figure 6.4). The concept of closure temperature was defined by Dodson (1973, 1979) as ‘the temperature of a system at the time of its apparent age’. A more recent discussion of this topic in the context of a wider discussion of thermochronology is given by Reiners et al. (2018).

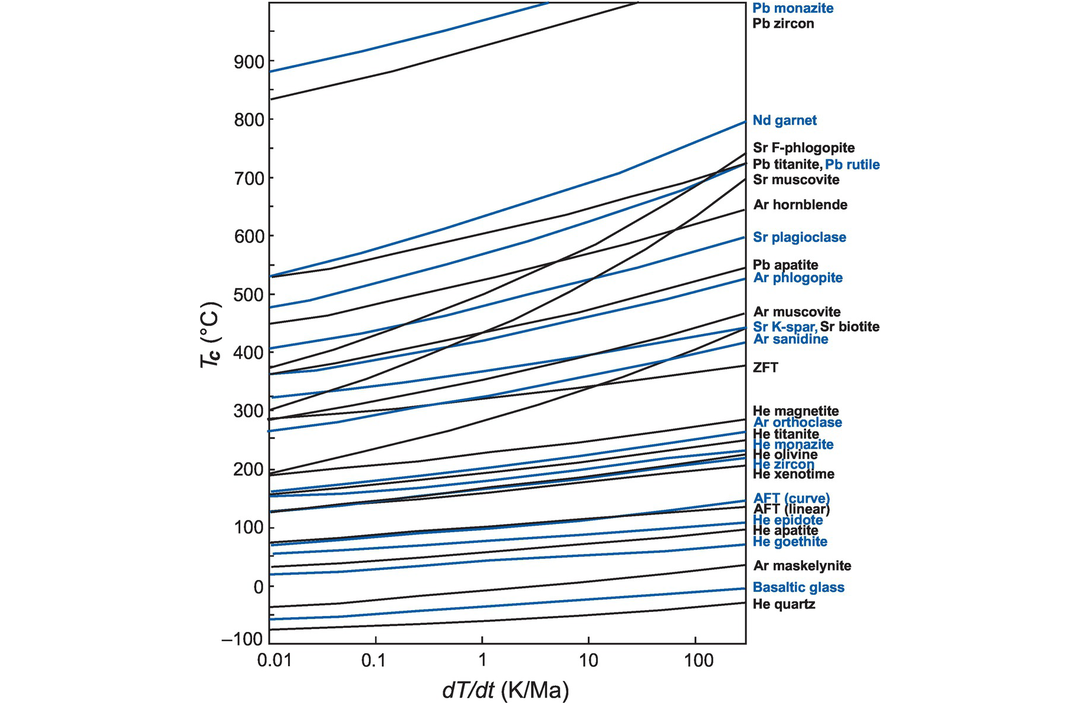

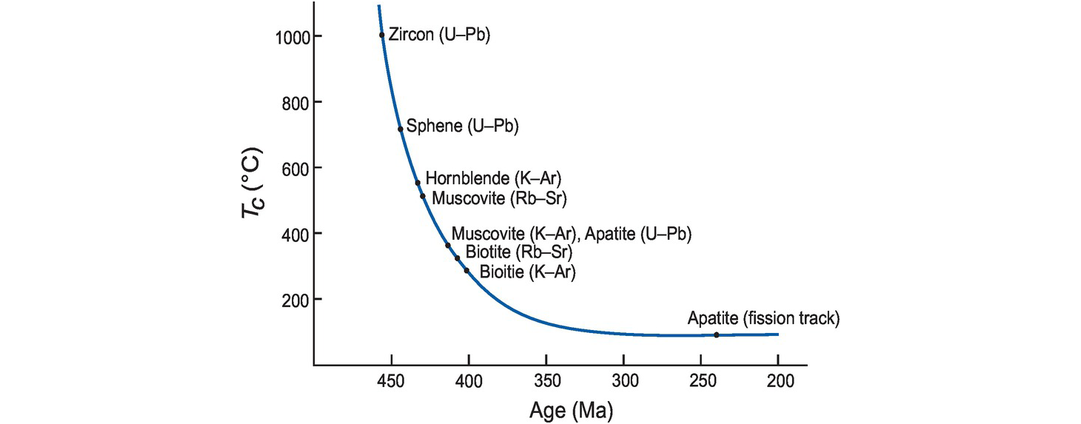

The Tc of a mineral depends on the thermally activated diffusion or annealing of radioisotopic daughter products, which in turn is a complex function of composition, grain size, grain shape, activation energy, cooling rate and whether or not a fluid is present to facilitate diffusion. For this reason, different minerals close at different temperatures and a single mineral will have a different Tc for each isotopic system (Table 6.5). It is unlikely, therefore, given the number variables that control the Tc, that there is a specific Tc for a given mineral associated with a particular isotopic system (Reiners, 2009; Cassata et al., 2011; Cassata and Renne, 2013). Even so, the cooling rate seems to exert the strongest influence on Tc, with a higher cooling rate generally producing a higher Tc (Figure 6.5). With this caveat in mind, Tc is most commonly used to describe minerals, and the Tc measured in several different minerals from a single rock may help to define the cooling history of that rock (Figure 6.6).

Closure (or blocking) temperature (after Dodson, 1979). (a) The cooling curve as a function of time. When a mineral is near its temperature of crystallisation (1) the daughter isotope will diffuse out of the mineral as fast as it is produced and cannot accumulate. As cooling continues, the mineral enters a transitional stage (between (1) and (2)) in which some of the daughter isotope is lost and some is retained, until finally at low temperatures the rate of escape is negligible and the daughter isotope is retained (2). (b) The accumulation curve of the concentration of the daughter to parent isotope as a function of time. The ‘age’ of the system (tB) is an extrapolation of the accumulation curve to the time axis (blue dashed line). The closure temperature (Tc) is the projection of this point onto the cooling curve in (a) (dotted line). Tc depends partly upon the cooling rate of the system but is independent of the starting temperature if the latter is sufficiently high. In a specific isotopic system, fast cooling rates have a higher Tc, while lower cooling rates have a lower Tc.

| Mineral | Reference | Tc (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| U–Th–Pb isotopic system | ||

| Monazite | Cherniak et al. (2004) | 1018 |

| Zircon | Cherniak and Watson (2001) | 974 |

| Rutile | Cherniak (2000) | 624 |

| Titanite | Cherniak (1993) | 645 |

| Apatite | Cherniak et al. (1991) | 473 |

| Lu–Hf isotopic system | ||

| Zircon | Cherniak et al. (1997)b | >900 |

| Garnet | Scherer et al. (2000) | ≥GtNd |

| Sm–Nd isotopic system | ||

| Diopside | Cherniak et al. (1997) | >750 |

| Titanite | Cherniak et al. (1997) | >700 |

| Garnet | Ganguly et al. (1998) | 690 |

| Apatite | Cherniak et al. (1997) | 400–1000 |

| Rb–Sr isotopic system | ||

| Biotite | Hammouda and Cherniak (2000) | 581 |

| Muscovite | Jenkin (1997) | 521 |

| Plagioclase | Jenkin et al. (1995) | 521 |

| K-feldspar | Cherniak and Watson (1992) | 396 |

| 40Ar/39Ar isotopic system | ||

| Hornblende (magnesian) | Harrison (1981) | 569 |

| Phlogopite | Giletti (1974) | 459 |

| Muscovite | Robbins (1972) | 393 |

| Biotite | Grove and Harrison (1996) | 358 |

| K-feldspar (low sanidine) | Wartho et al. (1999) | 357 |

| K-feldspar (orthoclase) | Foland (1994) | 222 |

| Maskelynite | Weiss et al. (2002) | 6 |

| (U–Th)/He isotopic system | ||

| Magnetite | Blackburn et al. (2007) | 247 |

| Titanite | Reiners and Farley (1999) | 212 |

| Monazite | Farley (2007) | 200 |

| Olivine | Shuster and Farley (2005) | 187 |

| Zircon | Reiners et al. (2004) | 184 |

| Xenotime | Farley (2007) | 176 |

| Epidote | Nicolescu and Reiners (2005) | 86 |

| Apatite | Farley (2000) | 69 |

| Goethite | Shuster et al. (2005) | 51 |

| Quartz | Shuster and Farley (2005) | 48 |

| Basaltic glass | Kurz and Jenkins (1981) | 24 |

| Fission track | ||

| Zircon | Rahn et al. (2004) | 342 |

| Apatite | Ketcham et al. (1999) | 115 |

| Fission track, He | ||

| Apatite, 4He 103 nmol/g | Shuster et al. (2006) | 109 |

| Apatite, 4He 102 nmol/g | Shuster et al. (2006) | 87 |

| Apatite, 4He 10 nmol/g | Shuster et al. (2006) | 69 |

| Apatite, 4He 1 nmol/g | Shuster et al. (2006) | 58 |

| Apatite, 4He 10−1 nmol/g | Shuster et al. (2006) | 53 |

The closure temperature (Tc) of some common minerals as a function of cooling rate (after Reiners et al., 2018; with permission from John Wiley & Sons). Note that fast cooling rates have higher Tc. The isotopic system and mineral are specified on the right-hand axis. ZFT, zircon fission track; AFT, apatite fission track.

The cooling history of the Glen Dessary syenite, Scotland (after Van Breemen et al., 1979, and Cliff, 1985). Mineral age is plotted against approximate Tc (with mineral and method indicated). The combination of different minerals and isotopic systems define a range of Tc and produce ‘cooling’ ages; these define the cooling history for the pluton which can be expressed as °C/Ma.

A distinction must be made between closure temperature and the resetting of an isotopic system. The latter will take place in samples which have been thermally overprinted and/or subject to fluid flow, and normally it is the process of fluid interaction that is more influential in resetting an isotopic system than temperature alone. Choosing between closure temperature (mainly controlled by volume diffusion) and the resetting of an isochron (most commonly a function of fluid flow) to explain discordant isotopic ages requires a consideration of the scale of isotopic homogenisation. For example, rocks which have been isotopically reset may yield a range of ages that vary from the time of crust formation to the most recent metamorphic event, and this may depend upon the scale of sampling such that large samples may escape isotopic re-homogenisation and preserve old ages, whereas individual minerals may have recrystallised and yield younger ages. In the following section we shall look more closely at the meaning of the term ‘age’ in the light of the Tc concept and discuss the different ways it has been used in both mineral and whole-rock systems.

6.2.3.2 What Is an ‘Age’?

In geochronology we distinguish between a ‘date’ and an ‘age’. The former is used to describe an analytical result that has not yet been interpreted or given any geochronological significance. The term ‘age’ is used when applied to the results of an isochron calculation or a model ‘age’ calculation on a whole rock or a mineral sample once the geological significance of the result has been evaluated. The meaning of the term ‘age’ is always a matter of interpretation, for there are a number of different processes that can impart geological significance to a calculated ‘age’. For this reason, the term ‘age’ is best used with an additional qualifying term. These are discussed below.

(a) Crystallisation age. The crystallisation age of a mineral or a rock records the time at which it crystallised. In an igneous rock the crystallisation age of a mineral records the magmatic age of the rock. In the case of a metamorphic mineral, if the temperature of crystallisation is lower than the closure temperature, the instant the mineral forms it records its age of crystallisation.

(b) Metamorphic age. A metamorphic age is the time of peak metamorphism. This is different from the cooling age, which is discussed below. A metamorphic age depends upon the metamorphic grade. In low-grade metamorphic systems the metamorphic maximum may be determined from the blocking temperature of a specific mineral. In the case of high-grade metamorphism, the time of the peak of metamorphism can be inferred from the resetting of a whole-rock system such as Rb–Sr or Pb–Pb or the timing of new zircon growth (Figure 6.8).

(c) Cooling age. In a metamorphic rock the term ‘cooling age’ describes the time, after the main peak of metamorphism, when for a given isotopic system a mineral passes through its closure temperature. In an igneous rock the cooling age is the time after solidification of the melt that a mineral passes through its closure temperature. A cooling age therefore must be specified in terms of both the isotopic system and the mineral (Figure 6.5).

(d) Crust formation age. A crust formation age represents the time at which new continental crust is extracted from the mantle (O’Nions et al., 1983). Normally, the genesis of new continental crust is followed by deformation, metamorphism and melting, and so it is not always possible to easily determine the age of crust formation, only the timing of the later metamorphism and/or partial melting.

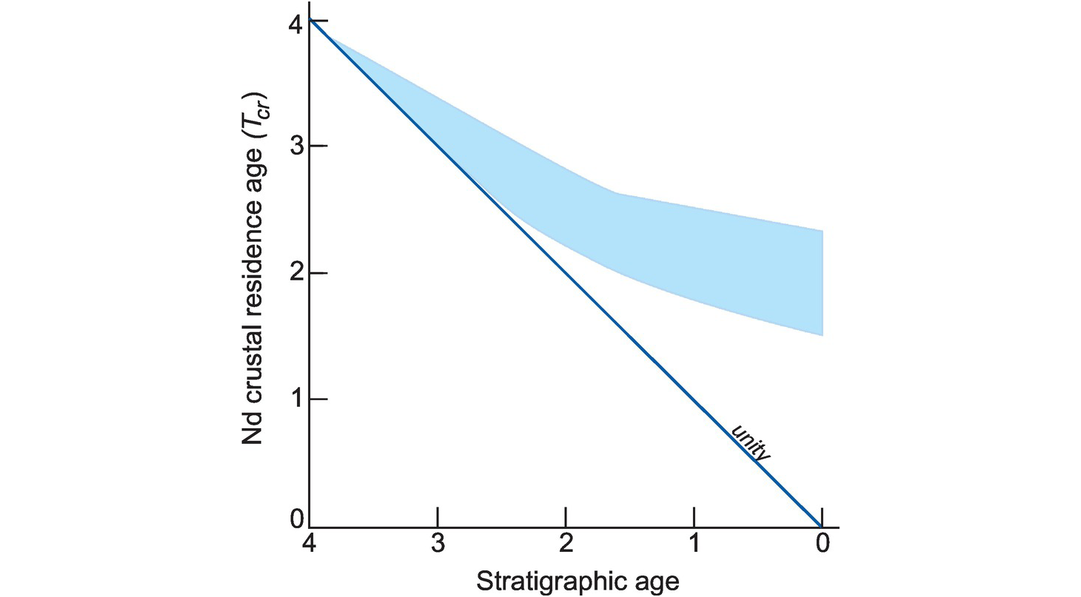

(e) Crustal residence age. The term ‘crustal residence age’ applies to sediment derived from an area of continental crust and reflects the age of that crust (Figure 6.7). A Nd crustal residence age (Tcr) is calculated from Eq. 6.5 by substituting appropriate values for the depleted mantle DM (the original source of the continental crust) in place of the values for CHUR. Some authors use the term ‘provenance age’ instead of crustal residence age, although this should not be taken to signify a specific event such as stratigraphic age, but rather is the average crustal residence time of all the components of the rock. Typically, the crustal residence age of a sedimentary rock is older than its stratigraphic age (Figure 6.7).

Crustal residence age (Tcr) diagram. Stratigraphic age is plotted against neodymium Tcr for fine-grained clastic sediments from 4.0 Ga to the present day (shaded region). The departure from the 1:1 line at about 2.5 Ga shows that Archaean sediments contain a mainly juvenile component, whereas Phanerozoic sediments contain an old crustal component.

6.2.4 Whole-Rock versus Mineral Age?

Choosing between a whole-rock or mineral age determination depends on the nature of the investigation. Useful age information may be extracted from whole rock systems as follows:

In rapidly cooled volcanic rocks, it is possible to measure the time of crystallisation.

In metamorphic rocks, whole-rock data can be used to measure the time of peak metamorphism.

In some instances, whole-rock model ages can be used to determine the time of crust formation.

Isotopic measurements of minerals can be used in mineral isochron calculations to determine individual mineral ages or the cooling history of a rock (see Section 6.2.3.1). Highly refractory minerals such as zircon with a high Tc can provide magmatic crystallization ages and sometimes even after multiple metamorphic events may preserve the time of crust formation. Minerals preserved as inclusions within refractory phases such as zircon, garnet or diamond can be protected from later overprinting events and may record the very early history or even the prehistory of the parent rock (e.g., Delavault et al., 2016).

The advent of analytical tools which permit the in situ, high spatial resolution measurement of isotope ratios in individual mineral grains has revolutionised geochronology (Compston, 1984; Košler et al., 2002). Not only can multiple analyses be made on a single crystal, helping to unravel the geological history of complex mineral grains, but the low-sampling volume associated with SIMS analysis permits multiple methods to be applied to the same analytical domain. For example, it is common to determine both the U–Pb age and the Hf isotope model age from within a single growth zone of a zircon crystal (Robinson et al., 2019) or both the U–Pb age and the REE chemical composition at the same analytical position in a single grain of zircon or garnet (Whitehouse and Platt, 2003).

6.2.5 Isotopic Systems Used in Geochronology

The reader should refer to Table 6.1 for the details of the radioactive decay schemes discussed in the sections below.

6.2.5.1 The K–Ar and Ar–Ar Systems

Within the family of the longer-lived radiogenic isotope systems used for dating geological events, 40K has one of the shortest half-lives. In addition, potassium is abundant in crustal rocks, whereas the concentration of the volatile noble gas Ar in the Earth is low, and so the Earth has a high 40K/40Ar ratio. For these reasons, the K–Ar system is the preferred method for accurately dating young events in fresh igneous rocks and, because of the volatility of Ar, measuring the time of reheating in igneous and metamorphic rocks. K–Ar ages are precise to about 30,000 years.

The 40Ar/39Ar method was developed from the K–Ar method. 39Ar does not occur naturally but is produced by irradiating a K-bearing sample with fast neutrons to produce 39K (half-life of 269 years). The amount of 39Ar produced is therefore a function of the amount of 39K present in the sample. Since at any point in the Earth’s history the 40K/39K ratio is constant, the amount of 40K present in the sample can also be calculated from the 39Ar measured. This forms the basis of 40Ar/39Ar dating.

Argon isotopes are most commonly measured in K-bearing minerals such as biotite, muscovite, K-feldspar and hornblende. The Tc associated with these minerals is in the ‘mid-temperature’ range (Tc = 200–550°C, Figure 6.5). At these temperatures, the closure temperature is highly dependent on the length scale of diffusion and the grain size and shape (Cassata et al., 2011; Cassata and Renne, 2013). This means that, depending on cooling rate, closure temperatures can vary by as much as ~200°C (Figure 6.5). Nonetheless, useful age data can be obtained from both K–Ar and 40Ar/39Ar methods and provide crystallization ages for rapidly cooled rocks, cooling ages in slowly cooled rocks (Rose and Koppers, 2019) and the time of diagenesis in sediments (Schomberg et al., 2019). Frequently, geochronological data are collected using a step heating method in which the cumulative 39Ar released is used to produce an age spectrum. Modern laser ablation systems allow micron-level spatial resolution of argon isotope measurements, and the in situ measurement of volcanic glass and minerals has been successfully applied using ~100-μm analytical spots (Warren et al., 2012).

6.2.5.2 The Rb–Sr System

The elements Rb and Sr are sufficiently abundant in most crustal rocks (10–1000 ppm) for the Rb–Sr method of geochronology to be useful in a wide range of rock types and minerals. However, Rb and Sr are also relatively mobile and the Rb–Sr isotopic system is frequently disturbed by the influx of fluids or by later thermal events. Consequently, Rb–Sr dating requires pristine samples and is rarely useful for constraining crust formation ages. Nevertheless, a Rb–Sr isochron has meaning and can usually be attributed to an event such as the time of metamorphism or recystallisation in an igneous rock or the time of diagenesis in a sedimentary rock.

The Rb–Sr method is often applied to the minerals biotite, muscovite, plagioclase K-feldspar and apatite. Ages can be calculated from a two-point isochron method in which a mineral with a low concentration of Rb such as plagioclase feldspar is used as a control on the initial ratio of the rock. Alternatively, mineral ages can be determined from single crystals or even parts of single crystals associated with specific metamorphic fabrics (Cliff et al., 2017).

6.2.5.3 The U–Th–Pb/He System

The utility of the U–Th–Pb system lies in its independent and branching decay schemes and in the contrasting geochemical properties of the elements involved. U and Th are actinides, incompatible and refractory. Under oxidizing conditions U exists as U6+ and can be highly mobile. Pb is slightly less incompatible, is chalcophile and exists in several oxidation states.

The focus here is on the Pb–Pb, 235U–207Pb and 238U–206Pb systems. U-series dating, which involves the numerous intermediate to short-lived daughter products within the U–Th–Pb system, is useful for dating very young geological processes but is not addressed here. Nor are the methods of the He fission track system that is used to determine the timing of low-temperature process associated with erosion. For a thorough discussion of these systems, we refer the interested reader to White (2015) and Reiners et al. (2018).

Pb–Pb whole-rock and mineral isochrons can be plotted for a wide range of rock types from granites to basalts, and can also be used to determine the depositional age of some sediments. The method yields reliable ages in rocks with simple crystallisation histories. However, the differences in U and Pb mobility and geochemical behaviour may complicate the interpretation if the isotopes have been reset. Thus, the Pb–Pb isochron method rarely provides crust formation ages and is better used to determine the age of metamorphism.

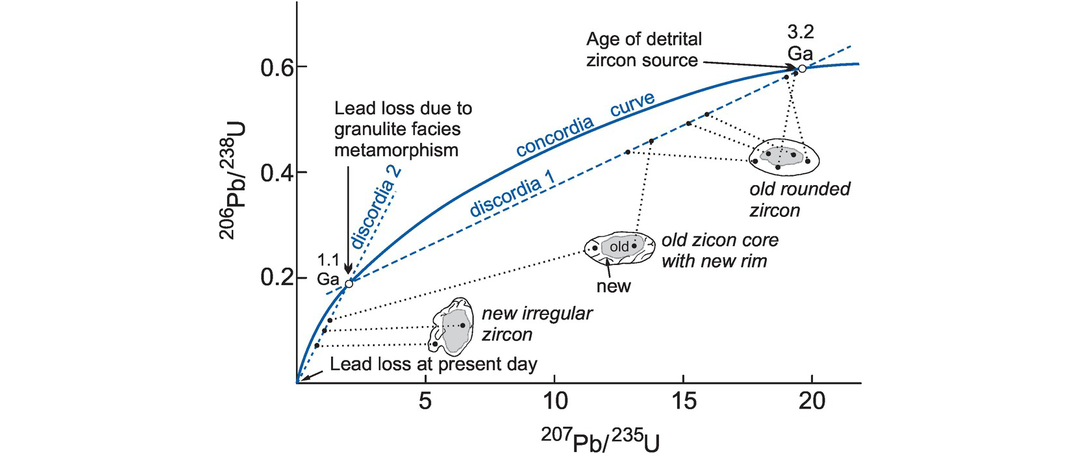

The combined use of the 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/235U systems allows an assessment of whether the assumptions associated with Tc have been met. This approach is commonly applied to mineral samples such as zircon. When samples which have had an undisturbed thermal history are plotted on a 206Pb/238U versus 207Pb/235U plot, they should lie on the ‘concordia’ curve (Figure 6.8). The concordia curve is the theoretical curve along which a series of 238U and 235U ages over time are the same (Figure 6.8, Box 6.1) and is calculated from the decay constants of the two systems. Hence a U-, Th-, Pb-bearing mineral population may define a linear array on a concordia diagram with an upper and lower time intercept on the concordia curve (Figure 6.8). The normal interpretation of the linear array, known as the discordia, is one of lead loss (or uranium gain) in which its upper and lower intercepts with the concordia curve may have petrological significance.

U–Pb concordia diagram. 207Pb/235U and 206Pb/238U data from zircon grains from a granulite facies metasediment from Sri Lanka (after Kroner et al., 1987). The concordia curve defines the theoretical evolution through time of 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/235U ages that are equivalent (Box 6.1). It is curved because 235U and 238U have different half-lives. A discordia is a line fitted to data points that are not concordant (do not coincide with the concordia curve). A discordia may intersect the concordia curve at two points. The sketches show morphologies of individual zircon grains and the locations analysed using a secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS). Old zircon grains and the cores of composite grains define a linear array (discordia 1) with an upper intercept at 3.2 Ga and a lower intercept at 1.1 Ga. The upper intercept is interpreted as the age of the source of detrital zircon and the lower intercept as the time of granulite facies metamorphism. New zircon grains (recognised on the basis of their irregular morphology) and new zircon overgrowth on composite grains define a second linear array (discordia 2) with an upper intercept at 1.1 Ga (the time of granulite facies metamorphism) and a lower intercept at the present day. The new zircon growth was interpreted to have occurred during the granulite facies event.

U and Th typically occur in zircon, monazite, rutile, titanite, epidote and apatite and so are often used in U–Th–Pb isotopic studies. Zircon in particular is a highly refractory mineral and so is especially useful since it can retain primary (crystallization) age information despite being affected by secondary processes (e.g., Reimink et al., 2016, and references therein). Thus, magmatic zircons in felsic rocks may be used to date the time of crystallisation from the upper intercept of the discordia curve. In contrast, granitic rocks which are melts of older crust may contain inherited (xenocrystic) zircons and in this case the lower intercept may represent the age of crystallisation, while the upper intercept may reflect the age of the crustal source (Amelin et al., 2000). In sediments, detrital zircons can reflect the age and composition of the sediment source (Zhang et al., 2015), and in metamorphic rocks zircons are used to date the age of the protolith and also the time of metamorphism (Hoiland et al., 2018). The application of high spatial resolution methods allows the dating of mineral growth zones within a single zircon grain and identification of the magmatic and, if applicable, the metamorphic chronology of the rock (Figure 6.8).

6.2.5.4 The Sm–Nd System

The REE elements Sm and Nd are incompatible and therefore are more abundant in the crust than in the mantle. They are less mobile than Rb, Sr, Th, U and Pb and so may preserve ‘original’ isotopic signatures in rocks whose Rb–Sr and Pb isotopic chemistry has been disturbed. The Sm–Nd isotope system is important in dating mafic rocks and meteorites where there is sufficient Sm/Nd fractionation to allow the accurate determination of an age and is one of the best methods for obtaining crust formation ages from a whole-rock analysis.

The chief limitations of the Sm–Nd method are associated with its long half-life, which restricts its application to older rocks, and the relatively small variations in Sm/Nd found in most cogenetic rock suites. For this reason, some workers have combined different lithologies on an isochron diagram to obtain a wider spread of Sm/Nd ratios, although this strategy requires a clear demonstration of their cogeneticity; otherwise, samples extracted from different sources and with very different histories will generate a questionable isochron.

Some accessory minerals such as apatite, monazite, sphene or garnet fractionate the REE and are useful in Sm–Nd mineral geochronology. Garnet is particularly important in this regard, for it has a high Tc (~500–700°C, Figure 6.5) and can be used to date the peak of metamorphism. Garnet-bearing mineral assemblages also offer the potential for precise Sm–Nd mineral isochron ages because garnet has a high Sm/Nd ratio which allows the slope of a mineral isochron to be accurately determined with errors of only 5–10 Ma for Mesozoic ages (Zheng et al., 2002; Lotout et al., 2020). Garnet ages are determined on two-point isochrons between garnet and whole-rock or one or more of the minerals plagioclase, pyroxene and hornblende with less fractionated Sm/Nd. Mineral isochrons which do not involve garnet are also possible but generally define a smaller range in Sm/Nd, although they may still yield ages with errors of ~20 Ma.

6.2.5.5 The Lu–Hf System

The Lu–Hf system is similar to the Sm–Nd isotopic system inasmuch as Lu is also a REE, but the half-life of 176Lu is shorter than 147Sm (37 Ga versus 106 Ga). This means that Lu/Hf and therefore 176Hf/177Hf in rocks and minerals should have a greater range than is seen by 143Nd/144Nd in the Sm–Nd system. Theoretically, the Lu–Hf method should permit precise isochron age determinations for older rocks. In practice, however, the lack of significant Lu/Hf fractionation in most crustal rocks and in common rock-forming minerals prevents this method from being used to determine isochron ages. Instead, the main applications are limited to those few specific minerals which fractionate Lu/Hf, as will be discussed in Section 6.3.1.2.

Lu is the heaviest of the REEs and it is especially accommodated in those phases that prefer the HREE. Garnet is an excellent example and most garnet species strongly partition Lu relative to the lighter REEs and Hf. In addition, Hf is chemically similar to Zr and is therefore concentrated in the mineral zircon. Although this is an advantage in simple igneous systems and allows the application of Lu–Hf and U–Pb dating methods to the same zircon grains, the different diffusion rates of trivalent Lu and tetravalent Hf cations means that interpreting the results for metamorphic rocks is not always straightforward (Bloch et al., 2020, and references therein).

An important application of the Lu–Hf method is in the study of clastic sediments. These tend to concentrate the heavy minerals such as garnet and zircon in which it is possible to apply multiple isotopic techniques including U–Pb, O, and Lu–Hf isotopes, as well as to analyse for trace elements and the REE. This means that in both modern and ancient sedimentary systems individual detrital mineral grains can be used to obtain information about both their source and the processes operating in the source region (Hoiland et al., 2017). When sufficient grains are analysed it is also possible to constrain their likely tectonic setting (Cawood et al., 2012).

6.2.5.6 The Re–Os System

In contrast to the highly lithophile elements of the Rb–Sr, Sm–Nd or Lu–Hf systems, the elements Re and Os are highly siderophile elements (HSE) and so are depleted in the silicate Earth and are present only at the ppb to sub-ppb levels. Both Re and Os are HSE elements, but Os is also a PGE and therefore is associated with ultramafic rocks, sulphides and arsenides. In mantle phases Re is moderately incompatible, whereas Os is highly compatible. This results in crustal rocks having elevated Re/Os ratios relative to the mantle. As noted above, the overall concentrations of Re and Os in the crust are low, but it is the strong fractionation of Re/Os and their enrichment in specific minerals that forms the basis of Re–Os geochronology.

Because crustal materials have very low concentrations of Re and Os, the application of the Re–Os system is restricted to samples enriched in Re and with high Re/Os. Re is particularly concentrated in molybdenite, to a lesser extent in Cu sulphides, and in black shales. This makes the Re–Os system useful in the study of iron meteorites, ore deposits, ultramafic rocks and hydrocarbons. Re–Os dating is based on the isochron method and combines related samples or minerals on an isochron (Kendall et al., 2006; Day, 2016). The method has also been used to date shales as young as 150 Ma (Cohen et al., 1999), and model ages in excess of 2 Ga have been calculated for Phanerozoic ophiolitic rocks (Meibom et al., 2002).

The Re–Os system has also been used to date mantle melt extraction events (Carlson, 2005). Os is compatible during mantle melting, whereas Re is moderately incompatible. Consequently, a melt residue will have lower Re and higher Os than either the fertile mantle or a mantle melt. This means that in residual peridotites the Re–Os system is less sensitive to contamination by migrating melts, thereby allowing whole rock mantle xenoliths to return useful chronological information on the timing of melt extraction.

6.2.5.7 Data Reduction Software Used in Geochronology

There are two free software packages commonly used for the reduction of geochronological data, Isoplot (Ludwig, 2009) and IsoplotR (Vermeesch, 2018b). Isoplot 4.15 (www.bgc.org/isoplot_etc/isoplot.html) is a PC-based add-on for Excel, and will work with some Mac Windows-enabling programs. Versions for older operating systems are also available. IsoplotR (www.ucl.ac.uk/~ucfbpve/isoplotr/) is a similar program written in R and can be used on-line or off-line with a computer that has R installed on it.

6.2.6 The Interpretation of Model Ages

A model age is an estimate of the time at which a sample separated from its mantle source region, and for igneous rocks and meta-igneous rocks this is a good estimate of the time of crust formation. However, as noted above in Section 6.2.2.4 a number of assumptions have to be made when calculating a model age.

In the case of Sr isotopes, none of these criteria is usually fulfilled with any certainty for either igneous rocks or sediments (Goldstein, 1988) and consequently model ages are not usually calculated for the Rb–Sr system. On the other hand, useful and meaningful model ages can be calculated for Nd, Hf and Os isotopes, although in each case the reference reservoir (CHUR or DM) must be specified and in the case of DM model ages the precise DM model evolution curve must also be defined.

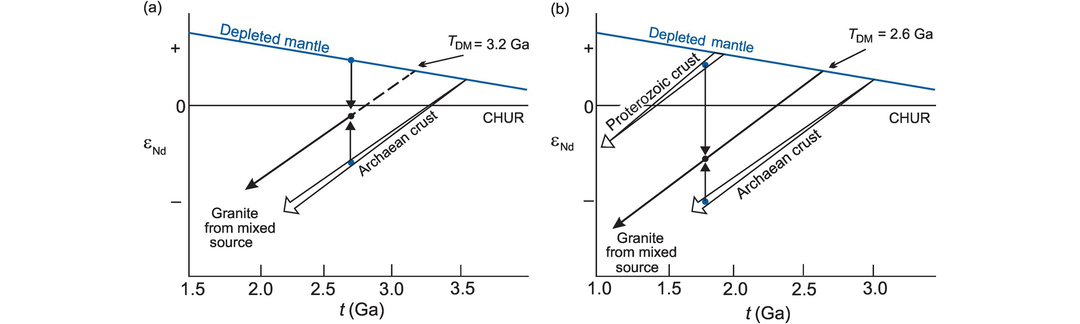

Model ages for granitoids may be used to estimate the age of their source. In the case of mantle-derived granites, the model age gives the time that the basaltic precursor to the granite was extracted from the mantle. This is often close in time to the crystallisation age of the granite. Granitoids which are derived by the melting of older continental crust give model ages which are indicative of the age of their crustal source, although this is realistic only when the parent/daughter element ratio has not been disturbed by fractionation. Often granites are a mixture of crustal and mantle sources. When this is the case calculated model ages provide only a minimum age (Arndt and Goldstein, 1987; Figure 6.9).

143Nd/144Nd evolution of the depleted mantle reservoir with time (in epsilon units; see Section 6.3.4). Relative to CHUR the depleted mantle shows increasing 143Nd/144Nd (increasingly positive εNd values) with time, whereas the continental crust shows retarded 143Nd/144Nd evolution (increasingly negative εNd values). (a) The depleted mantle model age for a granite formed at 2.7 Ga (black dot) from a mixture of a juvenile component derived from the depleted mantle and Archaean crust formed at 3.5 Ga will be 3.2 Ga. (b) The depleted mantle model age of a granite formed by the mixture of 1.9 Ga Proterozoic and 3.0 Ga Archaean crustal sources at 1.8 Ga will be 2.6 Ga. These diagrams show that model ages calculated for rocks with mixed sources provide only minimum ages of the crustal source.

Model ages for clastic sedimentary rocks provide an estimate of their crustal residence age (Section 6.2.3.2; O’Nions et al., 1983), again assuming minimal fractionation of the parent/daughter elements relative to the source. However, most continental sediment is a mixture of material from different sources. Consequently, model ages are likely to represent an average of the detrital input and provide only a minimum estimate of the crustal residence age or an average crustal residence age.

6.3 Using Radiogenic Isotopes in Petrogenesis

The mass difference between any pair of radiogenic isotopes is so small that the isotope pair cannot be fractionated by crystal–liquid processes. This means that during partial melting a magma retains the isotopic character of its source region and that isotope ratios remain unchanged during subsequent fractionation events.

These simple observations have led to two important developments in isotope geochemistry. First, source regions may have unique isotopic characteristics that can be defined, and, second, there may be mixing between isotopically distinct sources. Thus isotope geochemistry seeks to do the following:

A range of crust and mantle reservoirs is listed in Table 6.6 to demonstrate their isotopic variability. The larger and more difficult question of how the different crust and mantle reservoirs have acquired their isotopic signatures leads into the subject of crust and mantle geodynamics, a topic which treated briefly at the end of this chapter in Section 6.3.6.

| 87Rb–86Sr | 147Sm– 143Nd | 238U– 206Pb | 235U– 207Pb | 232Th– 208Pb | 176Hf/177Hf | 187Os/188Os | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic basaltic sources | |||||||

| DMMb | Low Rb/Sr | High Sm/Nd | Low U/Pb | Low U/Pb | Th/U = 2.4 ± 0.4 | 0.28330 | 0.1314–0.2316 |

| Low 87Sr/86Sr | High 143Nd/144Nd (positive εNd) | Low 206Pb/204Pb (~17.2–17.7) | Low 207Pb/204Pb (~15.4) | Low 208Pb/204Pb (~37.2–37.4) | |||

| HIMU | Low Rb/Sr | Moderate Sm/Nd | High U/Pb | High U/Pb | High Th/Pb | 0.28289 | 0.1305–0.1663 |

| low 87Sr/86Sr = 0.7029 | 143Nd/144Nd = <0.51282c | 206Pb/204Pb > 20.8 | high 207Pb/204Pb | (Mangaia) | |||

| EM-1 | Low Rb/Sr | Low Sm/Nd | Low U/Pb | Low U/Pb | Low Th/Pb | 0.28274 | 0.1342–0.1432 |

| 87Sr/86Sr (~0.705) | 143Nd/144Nd = <0.5112c | 206Pb/204Pb = 17.6–17.7 | 207Pb/204Pb = 15.46–15.49 | 208Pb/204Pb = 38.0–38.2 | (Gough) | ||

| EM-2 | High Rb/Sr | Low Sm/Nd | |||||

| 87Sr/86Sr > 0.722 | 143Nd/144Nd = 0.511-0.5121c | High 207Pb/204Pb and 208Pb/204Pb at a given 206Pb/204Pb | 0.282816 (Samoa) | 0.1173–0.1284 | |||

| Bulk Earth | 87Sr/86Sr = 0.7045 | 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512634 | 206Pb/204Pb = 15.58 ± 0.08 | 207Pb/204Pb = 18.4 ± 0.3 | 208Pb/204Pb = 38.9 ± 0.3 | 0.282843 | 0.1272–0.1303 |

| Continental crustal sources | |||||||

| Upper crust (sialic) | High Rb/Sr high 87Sr/86Sr | Low Sm/Nd low 143Nd/144Nd (negative εNd) | High U/Pb high 206Pb/204Pb | High U/Pb high 207Pb/204Pb | High Th/Pb high 208Pb/204Pb | 1.926 | |

| Mid crust | Semi-high Rb/Sr = 0.2–0.4 87Sr/86Sr = 0.72–0.74 | Crust shows retarded Nd evolution relative to chondritic source | U-depleted Low 206Pb/204Pb | U-depleted Low 207Pb/204Pb | Semi-high Th Semi-high 208Pb/204Pb | ||

| Lower crust (mafic) | Rb-depleted Rb/Sr < ~0.4 Low 87Sr/86Sr = 0.702–0.705 | Very U-depleted Very low 206Pb/204Pb (~14.0) | Very U-depleted Very low 207Pb/204Pb (~ 14.7) | Very Th-depleted Very low 208Pb/204Pb | 0.8040 | ||

a Disputed reservoirs are omitted (e.g., PREMA, FOZO, PHEM, C).

b Depleted MORB mantle.

c Normalized to 146Nd/144Nd = 0.7219.

Additional notes: 176Hf/177Hf from Salters and Stracke (2004) and Salters et al. (2011); 187Os/188Os MORB (Escrig et al., 2005), HIMU (Lassiter et al., 2003), EM-1 (Garapić et al., 2015), EM-2 (Jackson et al., 2016), BE (Van Acken et al., 2011, and references therein).

The isotopic variability between mantle sources may be thought of in terms of two separate processes. These are the process of mixing in which a number of different components contribute to the source, and the process of isotopic ingrowth in which the composition of the source evolves over geological time. Thus, radiogenic isotope ratios may be used to identify the separate components which have mixed to contribute to a particular magmatic suite such as in the case of the contamination of continental flood basalt with old continental crust. This mixing takes place over a relatively short time scale. In contrast, the isotopic evolution of a mantle source region as a function of the parent–daughter isotope ratio may take place over very long time scales – billions (Ga) rather than millions (Ma) of years.

Knowing how and when the different mantle sources acquired their separate identities is important for understanding the evolution of the Earth’s mantle, and it is this subject to which we now turn.

6.3.1 The Role of the Different Isotope Systems in Identifying Reservoirs and Processes

The elements used in geological radiogenic isotope studies vary greatly in their chemical and physical properties, so much so that different isotope systems vary in their sensitivity to particular petrological processes. This variability may show itself in three ways. First, the parent and daughter elements may under certain circumstances behave geochemically in different ways, such that the two become fractionated. For example, during mantle melting an element such as Rb is more readily concentrated in the crust than is the element Sr. The order of incompatibility for the elements of interest can be obtained from Figure 4.22 where the relative enrichments in MORB relative to the residual mantle and in the continental crust relative to MORB are shown.

A second possibility is that a parent–daughter element pair may behave coherently and so will not be fractionated, and yet behave in a very different manner from the parent–daughter pair of another isotopic system. For example, in the Sm–Nd and Lu–Hf systems the parent–daughter pairs share similar chemical and physical characteristics, whereas in the Re–Os, U–Th–Pb and Rb–Sr systems the parent–daughter pairs may be strongly fractionated relative to one another.

Finally, because of the geochemical similarity between the Sm–Nd and Lu–Hf isotope systems, it is reasonable to expect both systems to behave in a similar way and to display coupled geochemical behaviour. This is often evident on εNd versus εHf diagrams (Section 6.3.4). On occasion, the isotope systems display decoupled behaviour and this may also be of petrological significance.

We now briefly review some key geochemical properties of the Sr, Nd, Hf, Pb and Os systems. These are summarised in Table 6.6.

6.3.1.1 Sm–Nd Isotopes

In discussing the isotopes of Nd we differentiate between the long-lived Nd isotope system 147Sm→143Nd which is important in geochronology and the short-lived isotope system 146Sm→142Nd (half-life 103 Ma) which is relevant to our understanding of processes in the very early history of the Earth. The significance of the 146Sm→142Nd system is discussed more fully in Section 6.3.4.

The Sm/Nd ratio in the continental crust is lower than that of the depleted mantle and so over time generates lower 143Nd/144Nd ratios than are found in the depleted mantle. In this respect the Sm–Nd isotopic system is similar to Lu–Hf, but differs markedly from the U–Th–Pb, Rb–Sr and Re–Os systems. Since the elements Sm and Nd are not significantly fractionated after crust formation by subsequent metamorphic or sedimentary processes, Nd isotope ratios tend to preserve a memory of the parent–daughter isotope ratios of their source. In addition, Sm and Nd are immobile under hydrothermal conditions, and so Nd isotopes reflect the actual proportions of rock or magma involved in specific petrological processes, although this isotope system is insensitive to small amounts of recycled crust in the mantle.

6.3.1.2 Lu–Hf Isotopes

The Lu–Hf isotope system behaves in a similar way to the Sm–Nd isotope system. The Lu/Hf ratio in continental crust is lower than that in the mantle, and so with time the 176Hf/177Hf of the crust evolves to lower values relative to the Earth’s primitive mantle and the complementary depleted mantle evolves to higher values. A widespread and powerful application of Lu–Hf isotopes in petrology is the integration of Hf model ages with U–Pb crystallization ages for the mineral zircon. Recent studies have shown that in old continental crust, Hf model ages frequently exceed U–Pb zircon ages. This suggests that, if the U–Pb age represents the time of crystallisation of the crust, the Hf model age indicates an earlier event which is taken to be the time at which the precursor to the continental crust separated from the mantle (Kemp and Hawkesworth, 2014).

6.3.1.3 U–Th–Pb Isotopes

The U–Th–Pb system is more complex than other isotope systems used in geochemistry because it incorporates three independent decay schemes (Box 6.1) and because Pb isotopes do not define linear trends on lead isotope evolution diagrams. In terms of their geochemical behaviour U and Pb are incompatible in silicate minerals, although U enters a melt more readily than Pb, and U and Pb are relatively mobile in hydrothermal fluids, whereas Th is highly insoluble.

In detail the two isotopes of Pb produced from U decay (206Pb and 207Pb) show contrasting behaviour as a consequence of their differing radioactive decay rates (Box 6.1). Early in the history of the Earth 235U decayed rapidly relative to 238U, so that 207Pb evolved rapidly with time. Thus, 207Pb abundances are a sensitive indicator of an old source. Today, however, 235U is largely extinct so that in recent Earth history 238U decay is more prominent than that of 235U, and consequently the abundance of 206Pb shows a greater spread than 207Pb. This difference in behaviour between the Pb isotopes allows the identification of several isotopic reservoirs (Table 6.6). Crustal reservoirs are best sampled by studying the isotopic composition of a mineral with a low U/Pb or Th/Pb ratio such as feldspar for they preserve the ‘initial’ Pb isotopic composition of the source. This approach was developed by Doe and Zartman (1979), is now applied to single crystals using in situ analytical methods (Geng et al., 2020) and is discussed further in Section 6.3.6.1.

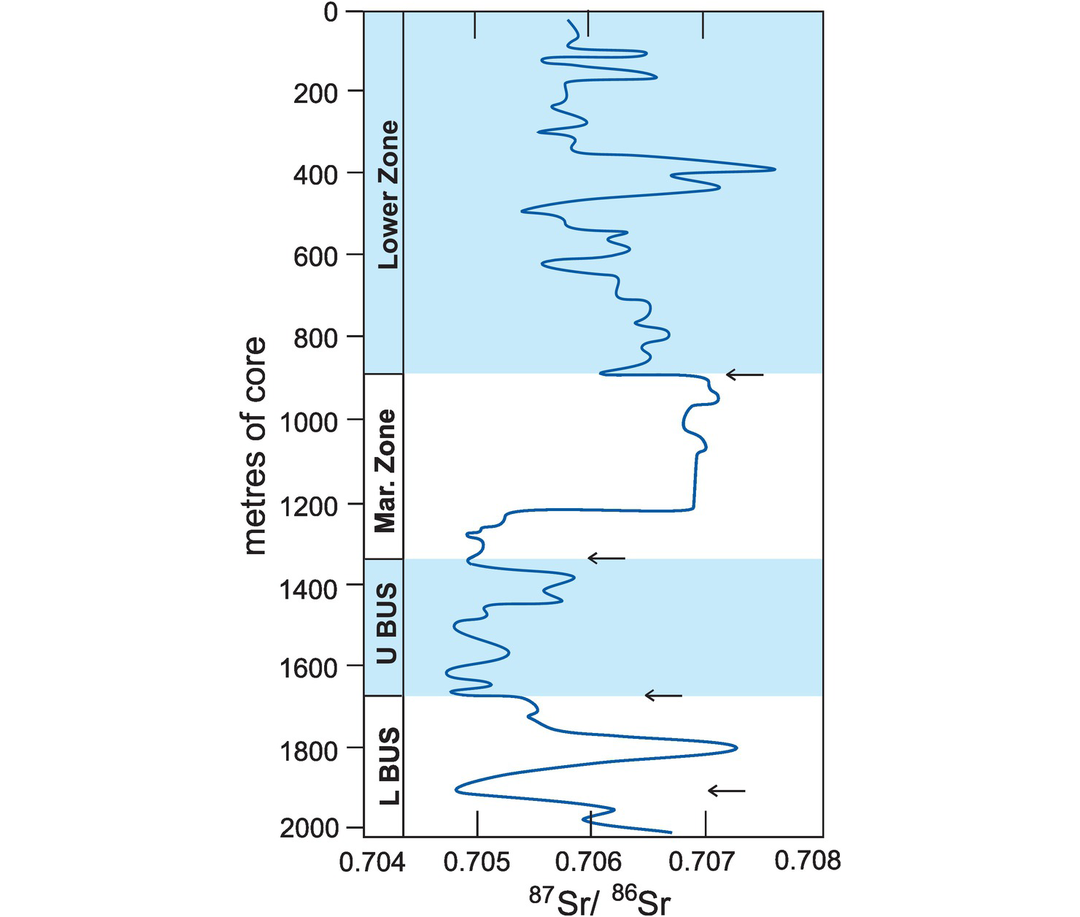

6.3.1.4 Rb–Sr Isotopes

During crustal melting the Rb–Sr isotope system has the greatest difference in compatibility between the parent and daughter elements. Rb and Sr are therefore easily separated and are strongly fractionated between crust and mantle. This results in the accelerated evolution of strontium isotopes in the continental crust relative to the mantle and with time has produced higher 87Sr/86Sr ratios than in the primitive mantle. Within the continental crust, Rb and Sr are further separated during re-melting, metamorphism and sedimentation because Sr is partitioned into plagioclase, whereas Rb is preferentially partitioned into the melt, and Sr is relatively immobile under hydrothermal conditions, whereas Rb is more mobile.

6.3.1.5 Re–Os Isotopes

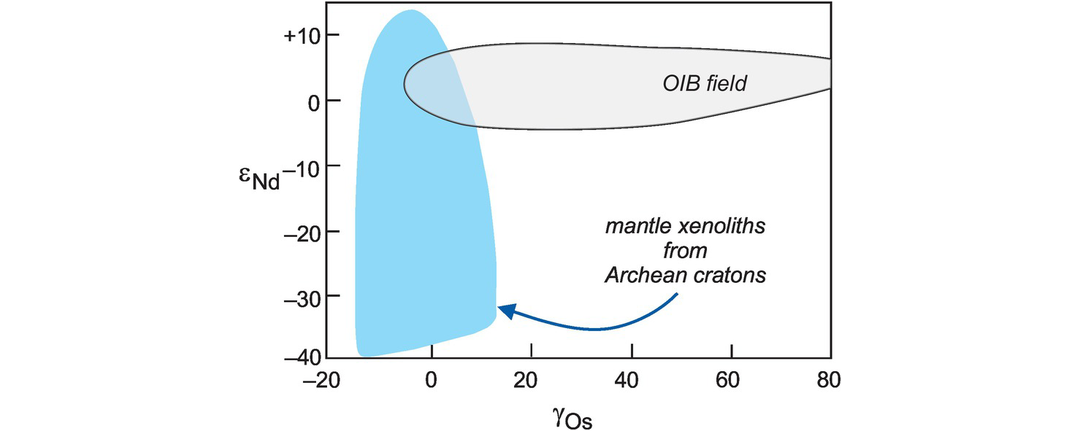

Re is moderately incompatible and Os highly compatible in the mantle. This results in crustal rocks having elevated Re/Os ratios relative to the mantle. In contrast, melt extraction from the mantle significantly lowers the Re/Os ratio of mantle peridotites and retards the in-growth of 187Os from the decay of 187Re. This allows the timing of melt extraction events to be estimated solely from their 187Os/188Os ratio (Walker et al., 1989), although melt percolation through the mantle may obscure this signal. Re–Os methods have been applied to the study of mantle xenoliths in order to date melt extraction events and identify a range of fertile, depleted and re-fertilised mantle sources.

6.3.2 Recognising Isotopic Reservoirs

Relative to the composition of the Earth’s primitive, undifferentiated mantle there are now a range of isotopically distinct reservoirs which can be recognised in both the mantle and the continental crust. Our purpose here is to show how these different reservoirs might be recognised on the basis of their present-day Sr, Nd, Hf, Pb and Os isotope chemistry (Tables 6.6 and 6.7).

Zindler and Hart (1986) first delineated four mantle end-member domains to explain the isotopic variation observed in mid-ocean ridge and ocean island basalts. In a simpler manner the continental crust can be divided into upper, middle and lower parts (Rundnick and Gao, 2014), each with distinctive geochemical and isotopic characteristics. In general, the upper and middle crust is more chemically evolved than the heterogeneous lower crust.

| Rock type | 87Sr/ 86Sr | 143Nd/144Nd | 206Pb/204Pb | 207Pb/204Pb | 208Pb/204Pb | 176Hf/177Hf | 187Os/188Os | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depleted mantle MORB (DMM) | ||||||||

| Atlantic | 0.702300–0.702920 | 0.512992–0.513175 | 18.084–19.437 | 15.440–15.568 | 37.51–38.77 | 0.283015–0.283354 | 0.137–0.2316 | 1, 2 |

| Pacific | 0.702150–0.702713 | 0.513098–0.513296 | 17.721–18.470 | 15.309–15.501 | 37.03–38.99 | 0.283165–0.283294 | 0.1315 | 1, 3 |

| Indian | 0.702690–0.704870 | 0.512437–0.513189 | 17.325–18.400 | 15.429–15.564 | 37.25–38.68 | 0.282768–0.283366 | 0.1295–0.3023 | 1, 4 |

| Ocean island basalts (OIB) | ||||||||

| Pitcairn Is. (EM1) | 0.703603–0.705296 | 0.512333–0.512692 | 17.72–18.10 | 15.47–15.50 | 38.61–39.03 | 0.282622–0.282834 | 0.1307–0.2539 | 5 |

| Samoa (EM2) | 0.705193–0.705853 | 0.512705–0.512900 | 18.78–19.41 | 15.55–15.65 | 38.77–39.86 | 0.282843–0.283099 | 0.1268–0.1394* | 5–9 |

| Continental flood basalts | ||||||||

| Parana/Etendeka | 0.70397–0.71420 | 0.511860–0.512799 | 17.1–19.7 | 15.5–15.7 | 37.5–38.9 | 0.282440–0.282440 | 0.1295 | 10–13 |

| Columbia River | 0.702985–0703964 | 0.512834–0.513031 | 18.71–18.92 | 15.55–15.59 | 38.10–38.53 | 0.282985–0.283114 | 0.134–0.404 | 14, 15 |

| Mantle xenoliths | ||||||||

| Continental lithosphere | ||||||||

| Siberia | 0.70253–0.702235# | 0.512590–0.513144# | 18.6–19.0 | 15.5 | 38.2–40.6 | 0.282837–0.283793# | 0.1156–0.1289# | 16, 17 |

| Oceanic lithosphere | ||||||||

| Hawai‘i | 0.703219–0.723422 | 0.513019–0.513180 | 18.06–18.45 | 15.45–15.49 | 37.80–38.04 | 0.283118–0.284630 | 0.1138–0.1269 | 18, 19 |

| Kimberlites/Lamproites | ||||||||

| Southern India | 0.700961–0.706647 | εNdt = −6.0 to −11.5 | 10.78–26.52 | 15.11–16.66 | 27.60–59.47 | εHft = +4.4 to −14.3 | 0.0967–0.5449 | 20, 21 |

| Ocean island arcs | ||||||||

| Marianas | 0.703440 | 0.512997 | 18.73 | 15.57 | 38.39 | 0.283235 | 0.1193–0.1274 | 22, 23 |

| Izu | 0.703352 | 0.513063 | 18.25 | 15.53 | 38.20 | 0.283248 | 0.1205–0.1272 | 22, 23 |

| Modern pelagic sediment | ||||||||

| Pacific | 0.70690–0.72253 | 0.512343–0.512392 | 16.72–19.17 | 15.57–15.75 | 38.43–39.19 | 0.283850–0.282901 | 1.044 | 24–26 |

| Atlantic | 0.709288–0.723619 | 0.511942–0.512553 | 18.61–19.01 | 15.68–15.74 | 38.93–39.19 | 0.282538–0.282960 | 1.044 | 25–27 |

| Modern trench sediment | ||||||||

| Global range | 0.70493–0.73631 | 0.51195–0.51291 | 18.55–19.49 | 15.52–15.81 | 38.17–39.76 | 28 | ||

| Terrigenous sediment | ||||||||

| Ganga River | 0.76913–0.78151 | 0.511736–0.511767 | 19.78–20.09 | 15.87–15.94 | 40.00–40.30 | 0.282133–0.282268 | 2.91–2.96 | 29, 30†, 31 |

| Turbidites | 0.51132–0.51306 | 16.91–19.91 | 15.50–15.90 | 36.44–40.02 | 0.281471–0.283153 | 25, 26 | ||

| Archean chemical sediments | ||||||||

| Stromatolite | 0.712396–0.726249 | εNdt = −3.6 to −7.4 | 14.1–20.9 | 14.9–16.2 | 33.3–35.4 | 32–34 | ||

| BIF | εNdt = +1 | |||||||

a Initial values; *, melt inclusions in ol or cpx; #, mineral + whole rock; †, suspended load.

References: 1, Chauvel and Blichert-Toft (2001) and references therein; 2, Escrig et al. (2005); 3, Bennett et al. (1996); 4, Yang et al. (2013); 5, Eisele et al. (2002) and references therein; 6, Reinhard et al. (2018); 7, Workman et al. (2004); 8, Jackson and Shirey (2011); 9, Sobolev et al. (2011); 10, Beccaluva et al. (2017); 11, Owen-Smith et al. (2017); 12, Rocha-Júnior et al. (2012, 2013); 13, Zhou et al. (2020); 14, Mullen and Weiss (2013); 15, Wolff et al. (2008); 16, Ionov et al. (2006); 17, Maas et al. (2005); 18, Bizimis et al. (2004, 2007); 19, Blichert-Toft et al. (2003); 20, Chakrabarti et al. (2007); 21, Rao et al. (2013); 22, Pearce et al. (1999) and references therein; 23, Parkinson et al. (1998); 24, McDermott and Hawkesworth (1991); 25, Vervoort et al. (1999); 26, Hemming and McLennan (2001); 27, Hoernle et al. (1991); 28, Plank (2014); 29, Galy and France-Lanord (2001); 30, Garcon and Chauvel (2014); 31, Levasseur et al. (1999); 32, Bolhar et al. (2002); 33, Kamber et al. (2004); 34, Alibert and McCulloch (1993).

Ultimately, it is important to understand how the different reservoirs in the crust and mantle have gained their isotopic character. Major processes include chemical depletion through melt extraction, re-fertilisation by melt addition and by the recycling of continental crust or oceanic crust into the mantle via subduction. Over geological time these processes can produce compositional and isotopic heterogeneities from the mineral grain scale to a global scale (Salters et al., 2011; Farmer, 2014; Hofmann, 2014; Stracke, 2016).

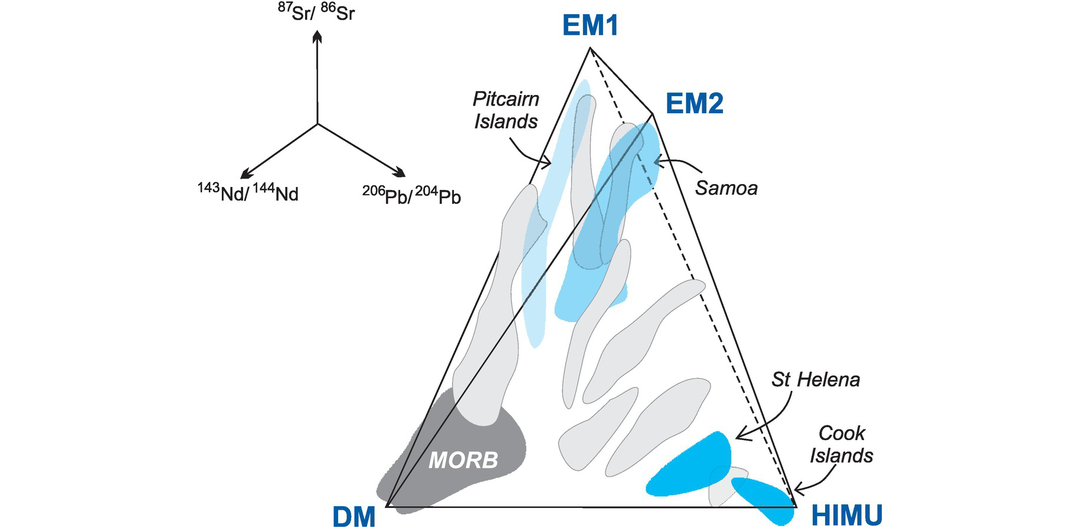

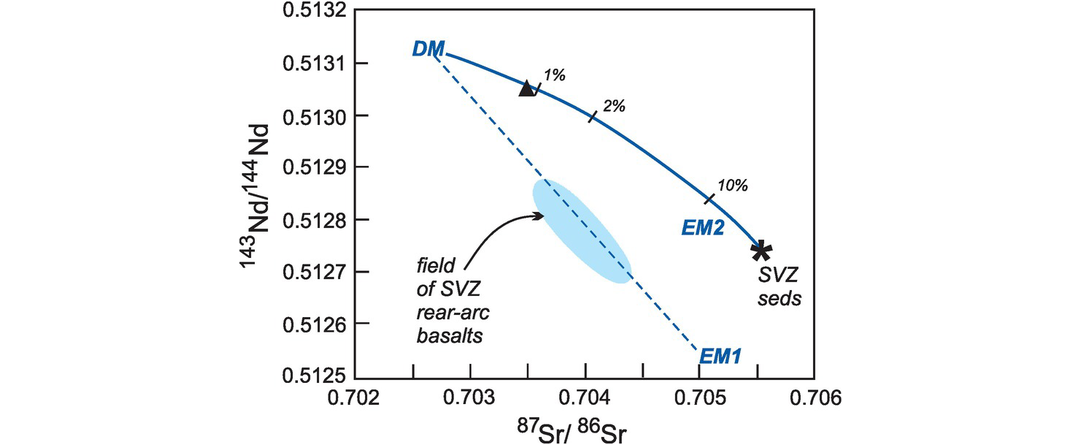

6.3.2.1 Oceanic Mantle Sources

Young magmatic rocks record the isotopic composition of their source directly, as insufficient time has passed in a newly formed magma for the parent isotope to produce a daughter isotope via radioactive decay in addition to that inherited from the source. Thus the present-day isotopic compositions of recent oceanic basalts were used by Zindler and Hart (1986) to identify four possible end-member mantle reservoirs. These reservoirs are well characterised for Sr, Nd, Hf and Pb isotopes, as summarized by Hofmann (2014) and Stracke (2016). The commonly accepted reservoirs are shown in Figures 6.10 and 6.11, are summarised in Tables 6.6 and 6.7 and are discussed briefly below.

(a) The Primary Uniform Mantle (PUM) reservoir. Geochemical models of the Earth assume an initial primary uniform mantle (PUM) reservoir. This is the composition of a homogeneous primitive or primordial mantle that would have formed during the early degassing of the planet after core formation but prior to the formation of the continents. The PUM is also known as the bulk Earth (BE) or the bulk silicate Earth (BSE). While some oceanic basalts have isotopic compositions similar to the PUM (McCoy-West et al., 2018), there are no geochemical data that require such a mantle domain exists today, although the PUM is a useful geochemical ‘frame of reference’ and is shown in most of the following diagrams.

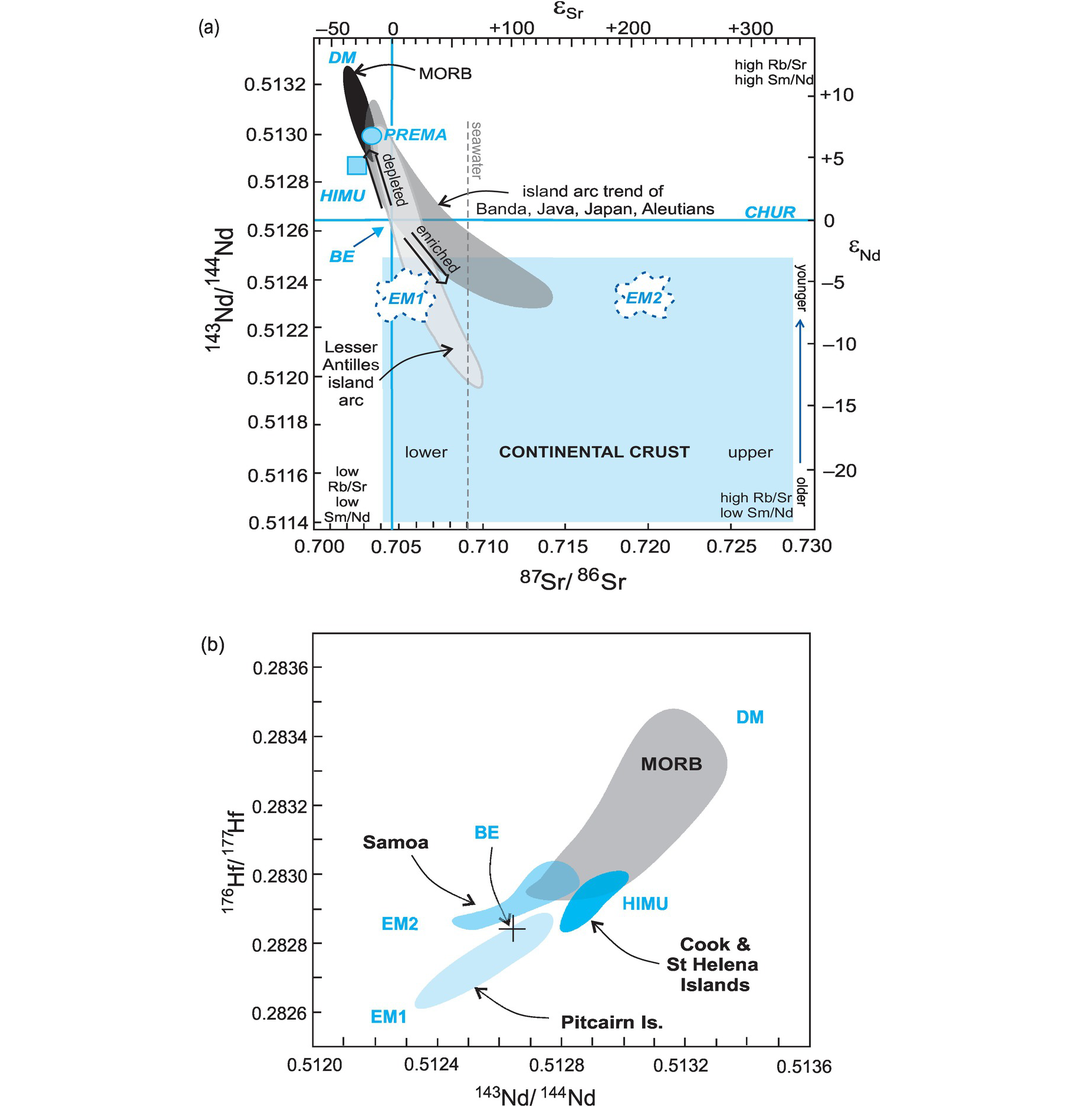

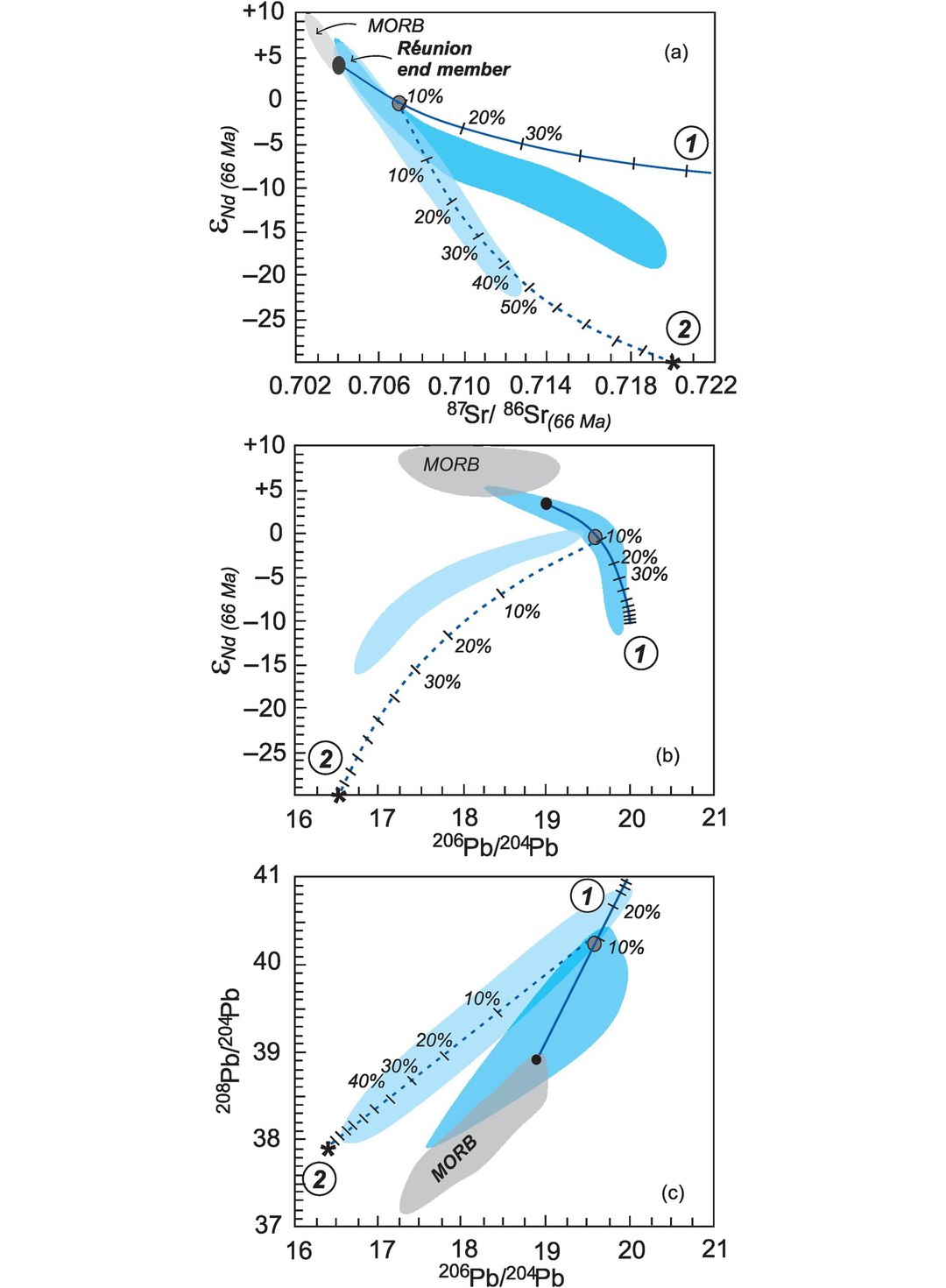

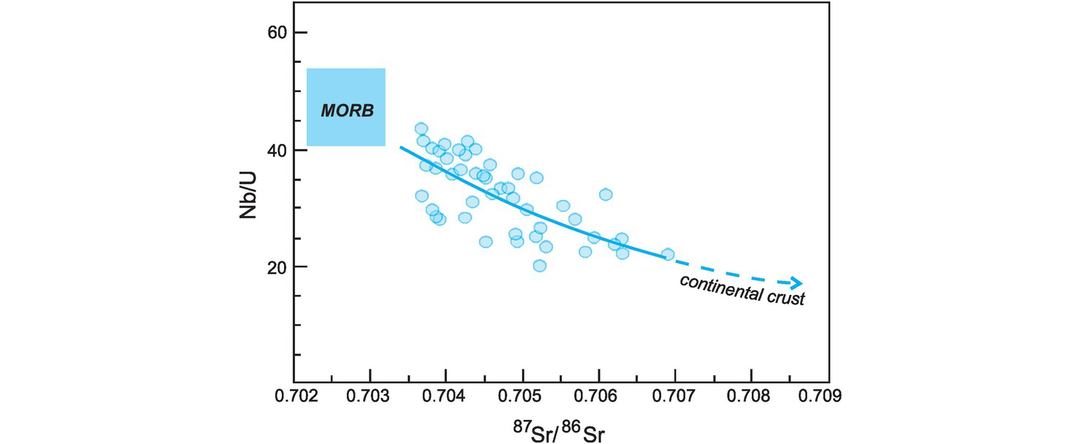

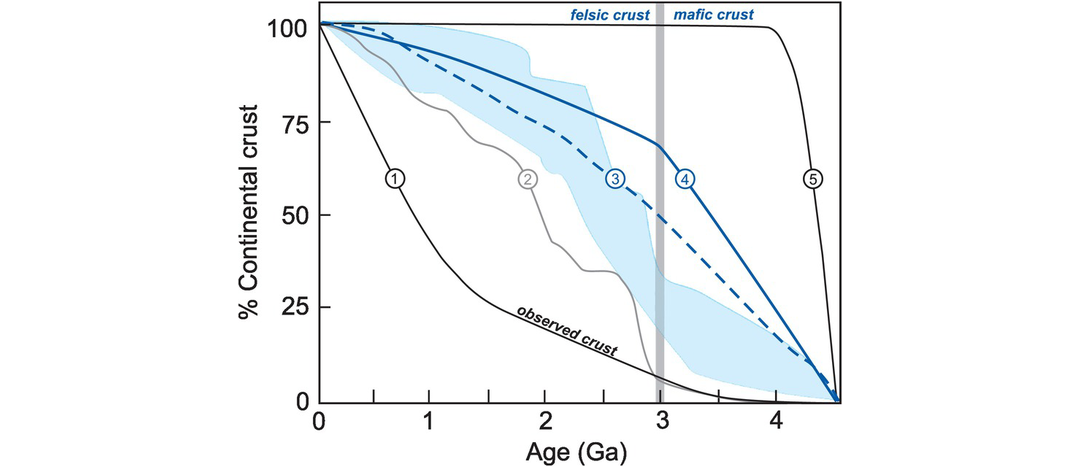

Mantle sources. (a) The 87Sr/86Sr versus 143Nd/144Nd diagram showing oceanic reservoirs for t = 0). These include the depleted mantle (DM), bulk silicate Earth (BE), enriched mantle (EM1, EM2), high-μ (U/Pb) (HIMU), and the ‘prevalent mantle’ (PREMA) compositions. The ‘depleted’ mantle reservoir in the upper left quadrant reflects residual mantle from which incompatible elements have been removed (it has been ‘depleted’). Most crustal rocks plot in the lower-right ‘enriched’ quadrant which includes old and young upper and lower crust. Mixing arrays between depleted mantle and enriched mantle sources are suggested by the island arc trends. Note the negative correlation between these two systems. Data compiled from Zindler and Hart (1986), Jackson et al. (2007) and White (2015). (b) The 143Nd/144Nd versus 176Hf/177Hf diagram of oceanic reservoirs with DM represented by global MORB, EM1 by volcanic rocks from the Pitcairn Islands, EM2 by volcanic rocks from the island of Samoa and HIMU by the Cook and St Helena Island volcanic rocks (after Stracke, 2016). The positive covariation on this diagram reflects the similar chemical behaviour of the parent/daughter elements in the two systems.

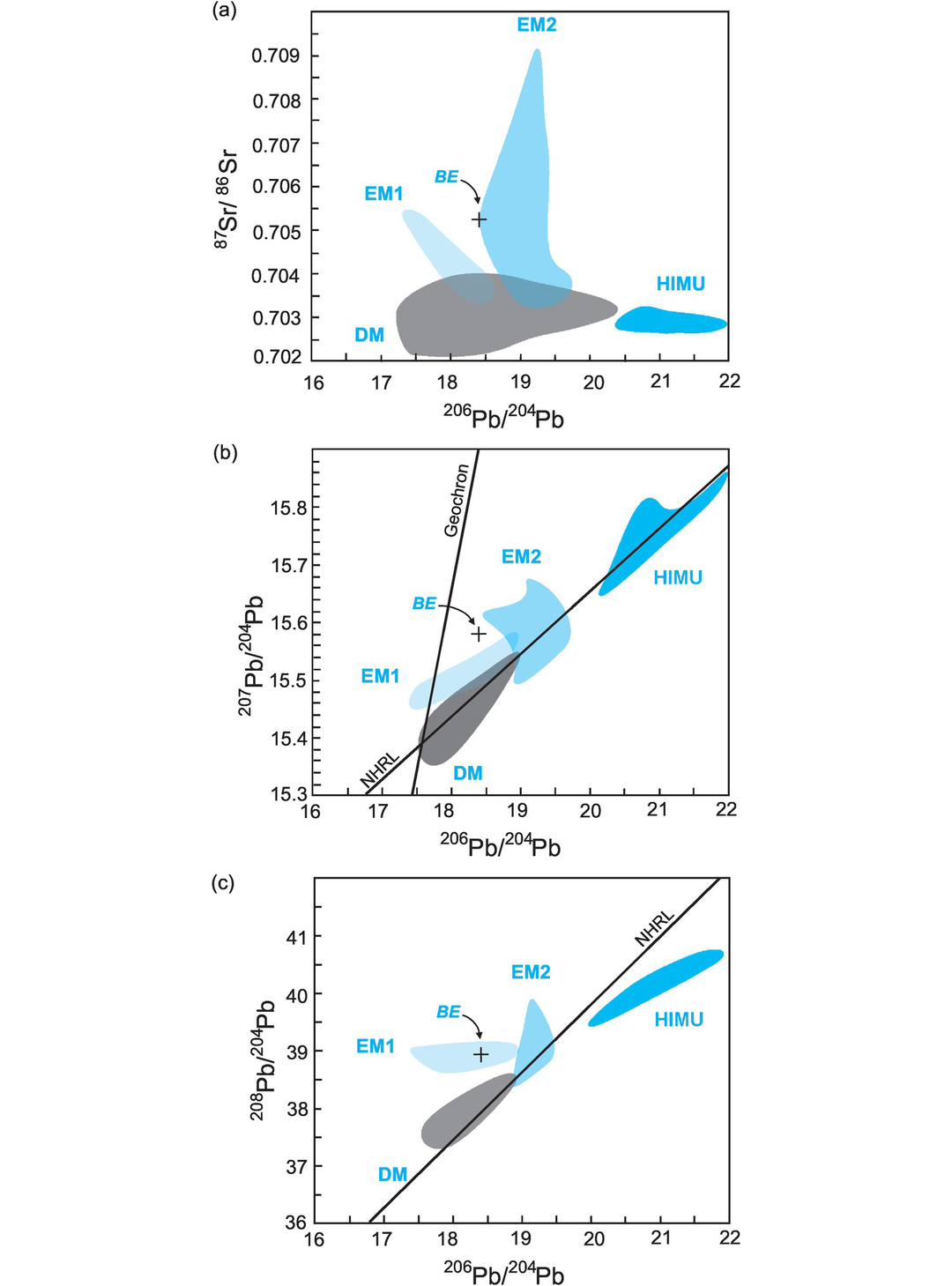

Mantle sources as defined by lead isotopes (data from Hofmann, 2014). (a) 206Pb/204Pb versus 87Sr/86Sr; (b) 206Pb/204Pb versus 207Pb/204Pb; (c) 206Pb/204Pb versus 208Pb/204Pb. Bulk silicate Earth (BE) is shown for reference (see Table 6.6 for values). The geochron assumes single-stage Pb-evolution from 4.55 Ga. NHRL is the Northern Hemisphere Reference Line (after Hart, 1984). Volcanic rocks which plot above the NHRL are said to have an enriched (DUPAL) signature. The non-controversial mantle reservoirs include the depleted mantle (DM) represented by global MORB, enriched mantle (EM1 by the Pitcairn Islands and EM2 by the island of Samoa), and high-μ mantle (HIMU) by the Cook and St Helena Islands. It is significant that the enriched mantle sources have some overlap with continental crustal sources (see Figure 6.10).

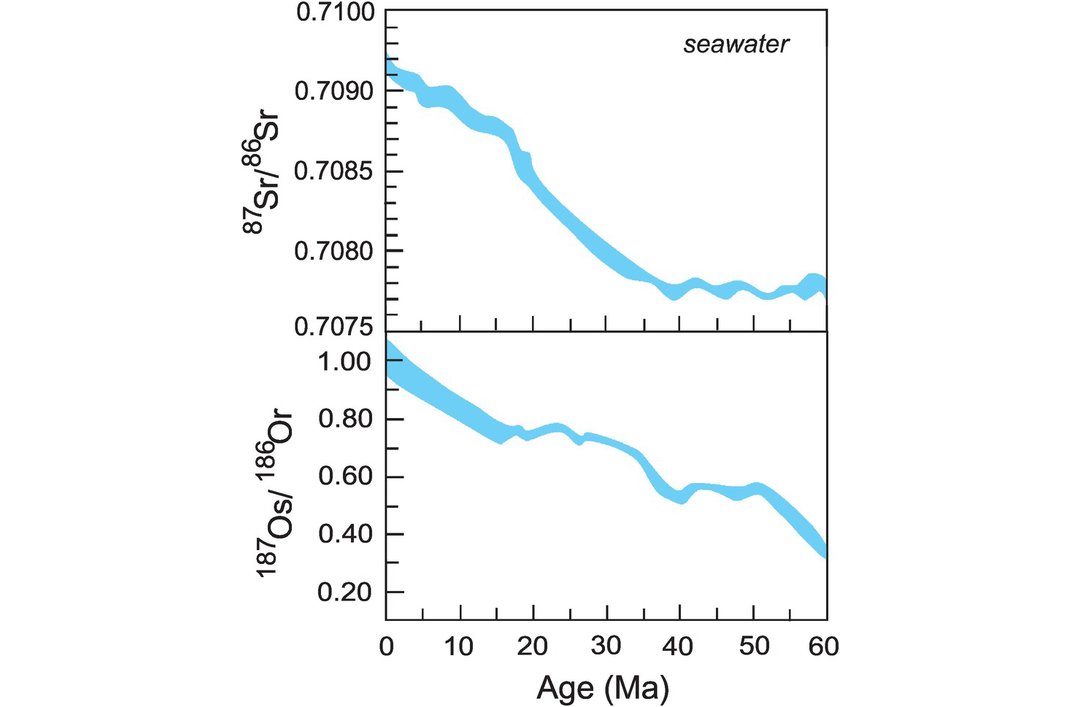

(b) The depleted mantle (DM) reservoir. The Earth’s depleted mantle is characterised by high Sm/Nd and low Rb/Sr element ratios. This leads to high 143Nd/144Nd and low 87Sr/86Sr isotope ratios. In addition, the DM has high 176Hf/177Hf and low 206Pb/204Pb. It is the primary source of most mid-ocean ridge basalts.