7.1 Introduction

Most naturally occurring elements consist of more than one stable isotope. In geochemistry the stable isotope systems of interest are those of the light elements H, C, N, O and S. These elements have been the subject of geochemical investigations for many decades and are termed the traditional stable isotopes. These are elements in which the mass difference between the different stable isotopes is sufficiently large to allow them to be fractionated through physical processes on the basis of their mass differences and in which the rarer isotope is of sufficient abundance to be measurable. They are often the main constituents of geologically important fluids and so provide the opportunity to study both the fluids and the effects of fluid–rock interaction.

Conventionally traditional stable isotopes are converted into a gas (usually H2, CO2 or SO2) for the purposes of isotopic analysis, and the mass differences measured in a mass spectrometer. With such commonly occurring elements as H, C, N, O and S contamination during sample preparation and analysis is a particular problem and great care must be taken to ensure clean sample handling. Increasingly, ion-beam and laser technologies are being used to obtain a finer spatial resolution of isotopic compositions in small samples. Traditional stable isotope studies typically measure the isotopic composition of a molecule or compound such as H2O or CO2 rather than the single element. This means that there are a number of different possible isotopic combinations within a single molecule. For example, carbon dioxide can exist as 12C16O2 (mass 44), as 13C16O2 or 12C17O16O (both mass 45), and there are many more possibilities. These different molecules are known as isotopologues; that is, they are molecules that differ from one another only in isotopic composition and may have the same or different masses. However, their abundances vary greatly. In the example given above, 12C16O2 makes up 98.4‰ of naturally occurring CO2, whereas 13C16O2 and 12C17O16O form only 1.11‰ and 748 ppm, respectively.

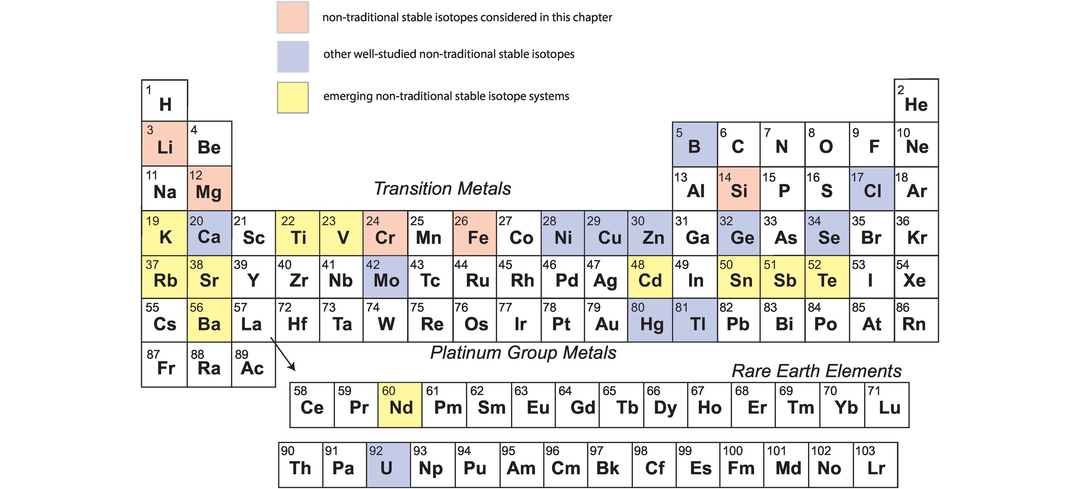

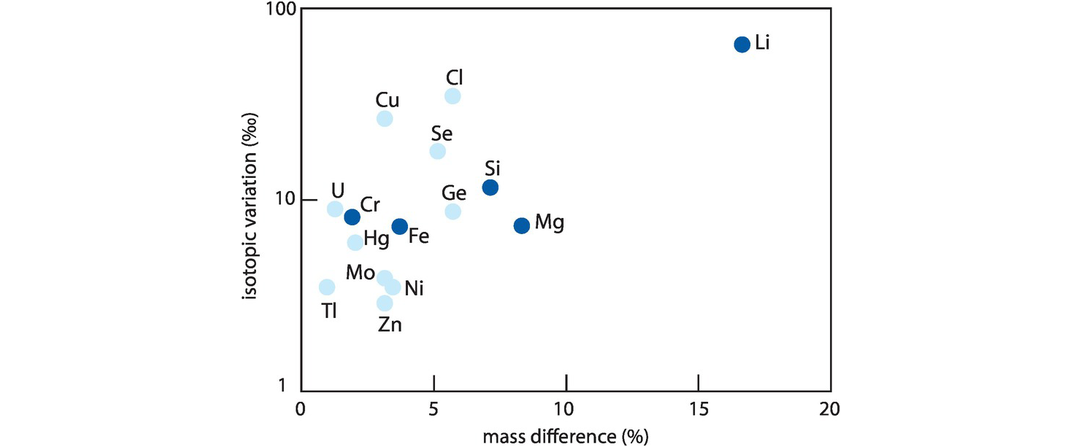

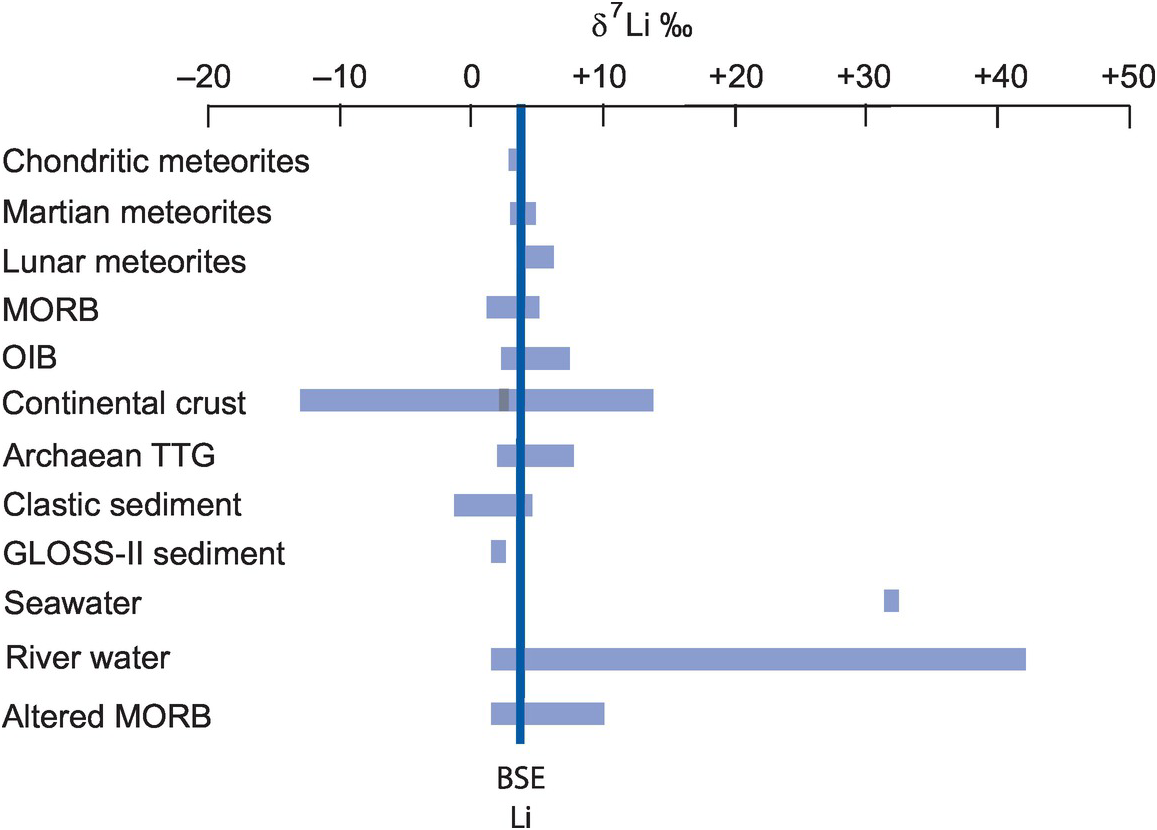

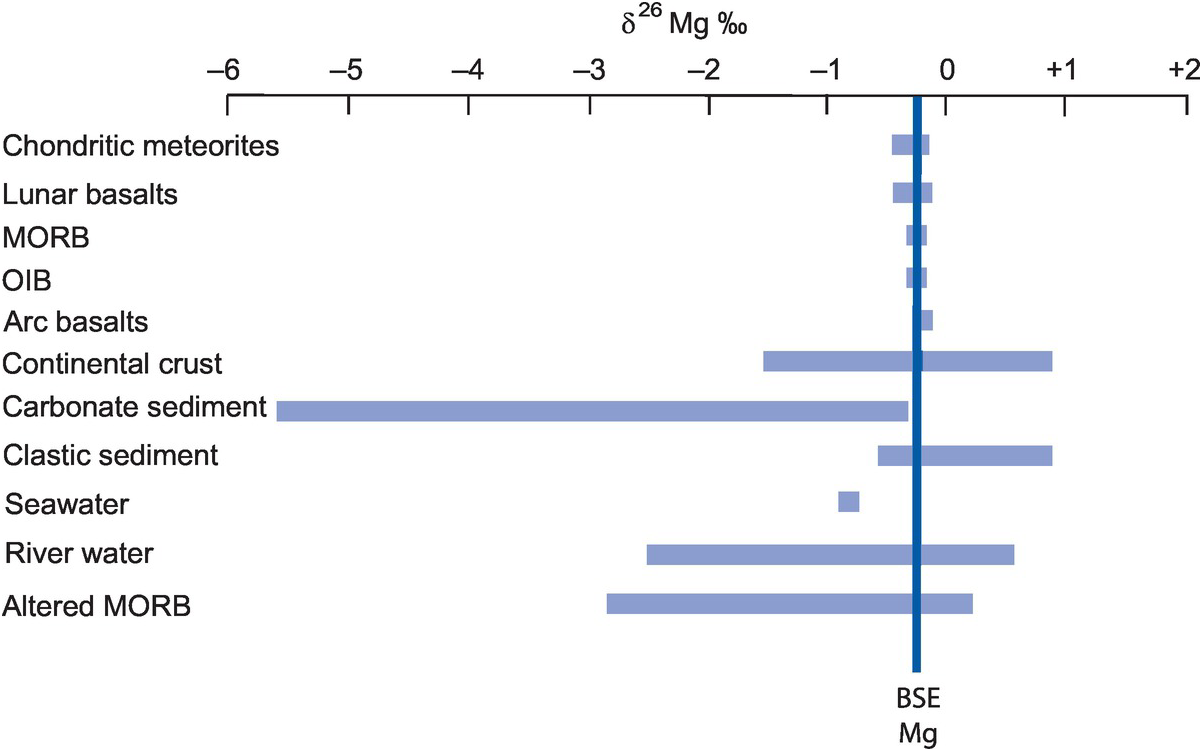

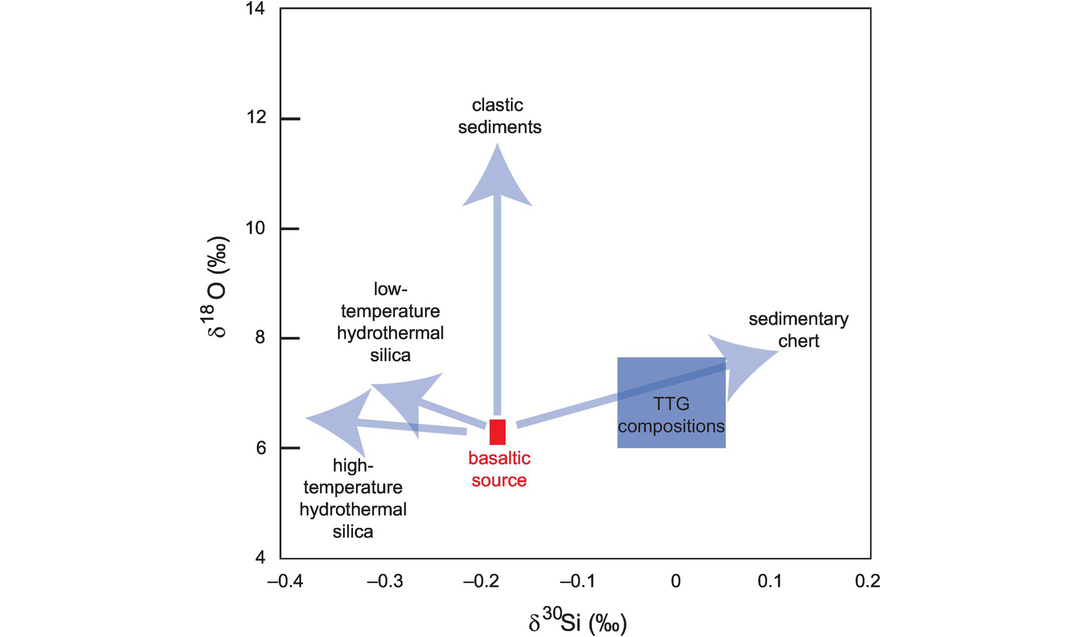

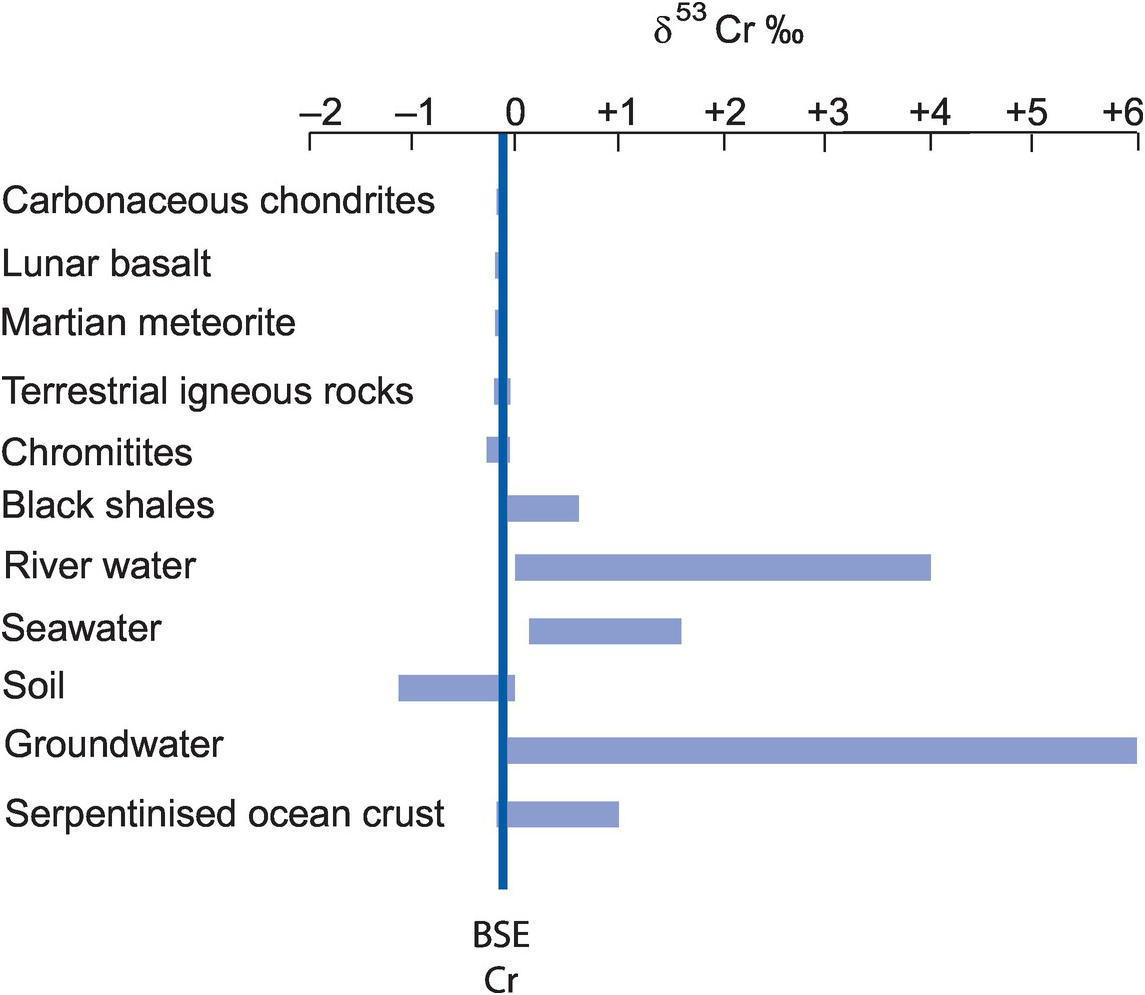

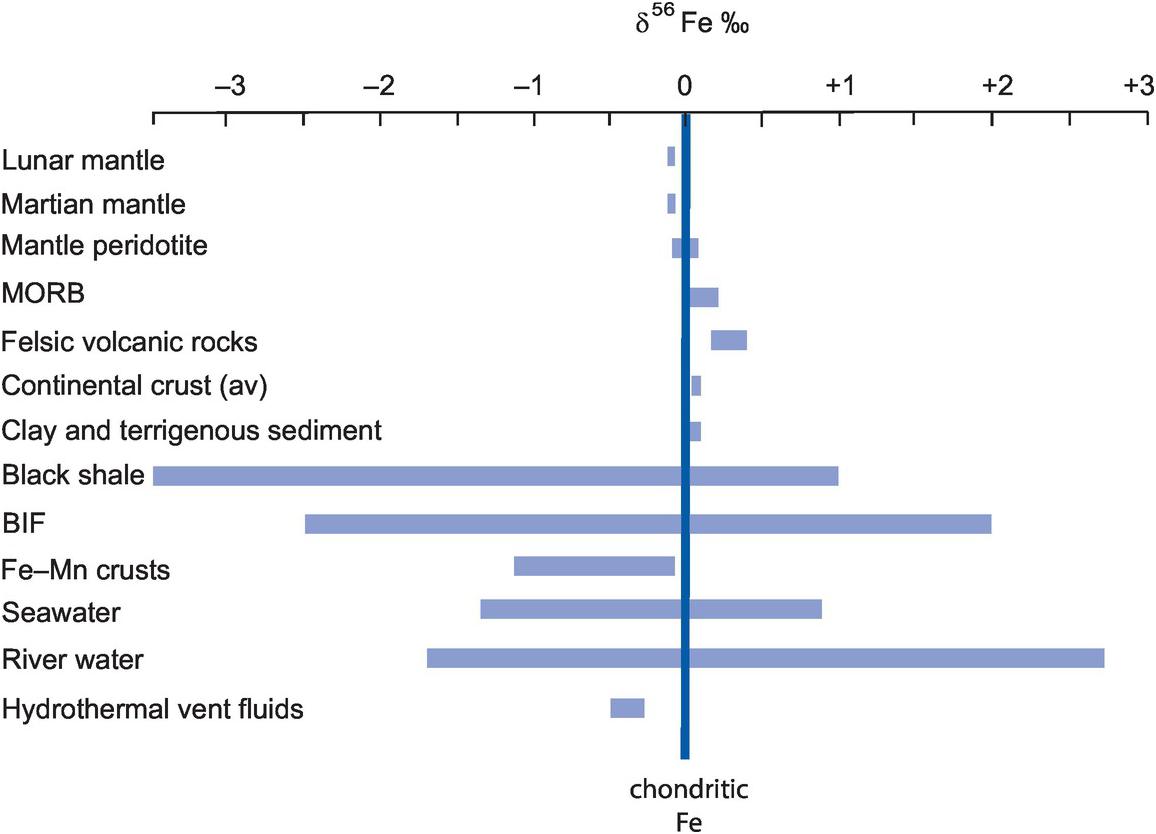

With the advent of multi-collector ICP-MS technology, a number of elements with higher atomic numbers, whose stable isotope variations had been regarded previously as too low to measure accurately, have been shown to have natural isotopic variations and added to the geochemical toolbox. These are often termed the non-traditional stable isotopes. Many occur as trace elements, some are redox sensitive, and some are biologically active, and because of their metallic nature some represent different bonding environments from the traditional covalently bonded stable isotopes. There are a large number of elements crowding into this field, with others emerging. Here we consider five of the non-traditional stable isotopes – the light elements Li, Mg and Si and the heavier elements Cr and Fe – to illustrate their diverse applications in modern geochemistry.

In this chapter we first consider in Section 7.2 some of the key principles behind interpreting stable isotope geochemistry, then in Section 7.3 there is a discussion of the application of the traditional stable isotopes H, C, N, O and S. This is followed in Section 7.4 by a discussion of the application of the non-traditional stable isotopes Li, Mg, Si, Cr and Fe. More detailed treatments of the traditional stable isotopes are given by Valley et al. (1986), Taylor et al. (1991), Sharp (2017) and Hoefs (2018), and for the non-traditional stable isotopes, Teng et al. (2017a).

7.2 Principles of Stable Isotope Geochemistry

7.2.1 Notation

7.2.1.1 Isotope Ratios: The δ Value

Stable isotope ratios are measured relative to a standard, and because the relative differences are normally very small, they are expressed in parts per thousand (informally as ‘per mil’): ‰. The isotope ratio is expressed as a δ (delta) value, or del value as it is sometimes colloquially called. Using oxygen isotopes as an example, the δ value is calculated as follows:

Thus a δ18O value of +10.0‰ means that the sample is enriched in the 18O/16O ratio relative to the standard by 10 parts in thousand and is isotopically ‘heavy’. Similarly, a negative value of −10.0‰ means that the sample is depleted in the 18O/16O ratio relative to the standard by 10 parts in a thousand and is isotopically ‘light’.

7.2.1.2 The Fractionation Factor α

The fractionation of an isotope between two substances A and B can be defined by the fractionation factor

For example, in the reaction in which 18O and 16O are exchanged between magnetite and quartz, the fractionation of 18O/16O between quartz and magnetite is expressed as

where ‘18O/16O in quartz’ and ‘18O/16O in magnetite’ are the measured isotopic ratios in coexisting quartz and magnetite. If the isotopes are randomly distributed over all the possible atomic positions in the compounds measured, then α is related to an equilibrium constant K such that

where n is the number of atoms exchanged. Normally, exchange reactions are written such that only one atom is exchanged, in which case α = K, and the equilibrium constant is equivalent to the fractionation factor.

Values for α are close to unity and typically vary in the third decimal place. Most values therefore are of the form 1.00X. For example, the fractionation factor for 18O between quartz and magnetite at 500°C is 1.009 (Javoy, 1977). This may be expressed as the third decimal place value – the per mil value – such that the quartz–magnetite fractionation factor is 9 (or 9.0 per mil). A useful mathematical approximation for the fractionation factor α stems from the following relationship:

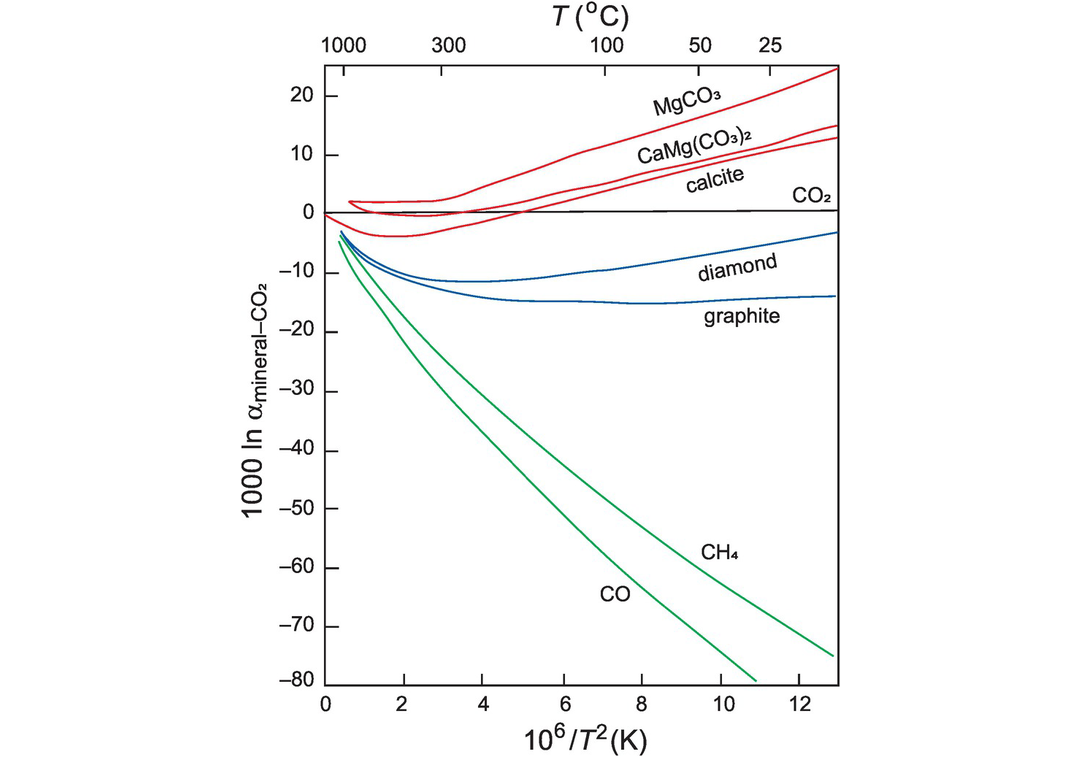

In the case cited above where α = 1.009, 1000 ln α = 9.0. Experimental studies have shown that 1000 ln α is a smooth and often linear function of 1/T2 for mineral–mineral and mineral–fluid pairs. This gives rise to the general relationship for the fractionation factor

where T is in Kelvin and A and B are constants, normally determined by experiment. In the case of the quartz–magnetite pair the values for A and B are 6.29 and 0, respectively (Chacko et al., 2001), giving the expression:

A further useful approximation is the relationship between 1000 ln α and measured isotope ratios expressed as δ values. The difference between the δ values for two minerals is expressed as Δ which approximates to 1000 ln α, when the δ values are less than 10. In the case of oxygen isotopic exchange between quartz and magnetite,

When δ values are larger than 10, then the following expression should be used:

A range of approaches is used to obtain stable isotope fractionation factors. These include theoretical calculations based upon models of atomic structure and bond strength, experimental studies, and empirical investigations based upon well-studied natural samples (see Chacko et al., 2001, for a review; Sharp 2017). These authors also provide a helpful compilation of self-consistent, experimentally determined mineral–mineral fractionation factors (values for A) for oxygen isotopes, which is summarised here in Table 7.1.

| Cc | Ab | Ms | F-Phl | An | Phl | Ap | Zn | Alm | Di | Gr | Gh | Ttn | Fo | Ru | Mt | Pv | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qz | 0.38 | 0.94 | 1.37 | 1.64 | 1.99 | 2.16 | 2.51 | 2.64 | 2.71 | 2.75 | 3.15 | 3.50 | 3.66 | 3.67 | 4.69 | 6.29 | 6.80 |

| Cc | 0.56 | 0.99 | 1.26 | 1.61 | 1.78 | 2.13 | 2.26 | 2.33 | 2.37 | 2.77 | 3.12 | 3.28 | 3.29 | 4.31 | 5.91 | 6.42 | |

| Ab | 0.43 | 0.70 | 1.05 | 1.22 | 1.57 | 1.70 | 1.77 | 1.81 | 2.21 | 2.56 | 2.72 | 2.73 | 3.75 | 5.35 | 5.86 | ||

| Ms | 0.27 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 1.14 | 1.27 | 1.34 | 1.38 | 1.78 | 2.13 | 2.29 | 2.30 | 3.32 | 4.92 | 5.43 | |||

| F-Phl | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 1.51 | 1.86 | 2.02 | 2.03 | 3.05 | 4.65 | 5.16 | ||||

| An | 0.17 | 0.52 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 1.72 | 1.51 | 1.67 | 1.68 | 2.70 | 4.30 | 4.81 | |||||

| Phl | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.99 | 1.34 | 1.50 | 1.51 | 2.53 | 4.13 | 4.64 | ||||||

| Ap | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 1.15 | 1.16 | 2.18 | 3.78 | 4.29 | |||||||

| Zn | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.86 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 2.05 | 3.65 | 4.16 | ||||||||

| Alm | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 1.98 | 3.58 | 4.09 | |||||||||

| Di | 0.28 | 0.75 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 1.94 | 3.54 | 4.05 | ||||||||||

| Gr | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 1.66 | 3.26 | 3.77 | |||||||||||

| Gh | 0.16 | 0.17 | 1.19 | 2.79 | 3.30 | ||||||||||||

| Ttn | 0.01 | 1.03 | 2.63 | 3.14 | |||||||||||||

| Fo | 1.02 | 2.62 | 3.13 | ||||||||||||||

| Ru | 1.60 | 2.11 | |||||||||||||||

| Mt | 0.51 |

Isotopic fractionations between minerals and melt vary as a result of the changing composition of the melt. Mineral–melt fractionations are defined in the same way as for mineral pairs (Eq. 7.2) and these values are particularly useful when seeking to calculate the stable isotope composition of a melt from the isotopic composition of one or more refractory or phenocryst phases. Other approaches used to measure the isotopic composition of a melt include the direct measurement of the fresh glass, or to treat the melt as a mixture of normative minerals with a fractionation factor calculated from the weighted average of the fractionation factors of the normative minerals (Bindeman, 2008).

7.2.2 Equilibrium Stable Isotope Fractionation

One of the most fundamental concepts behind stable isotope fractionation is that the mass of an atom affects its translational, rotational and vibrational motions and thus the strength of its chemical bonds. Most isotopic fractionations are the result of equilibrium effects and follow the rules of equilibrium thermodynamics. This means that equilibrium fractionation between two phases is based upon the differences in the bond-strength of the different isotopes of the element. The heavier isotope will form the stronger, stiffer bond. So that when an isotope is partitioned between two minerals in an exchange reaction such as

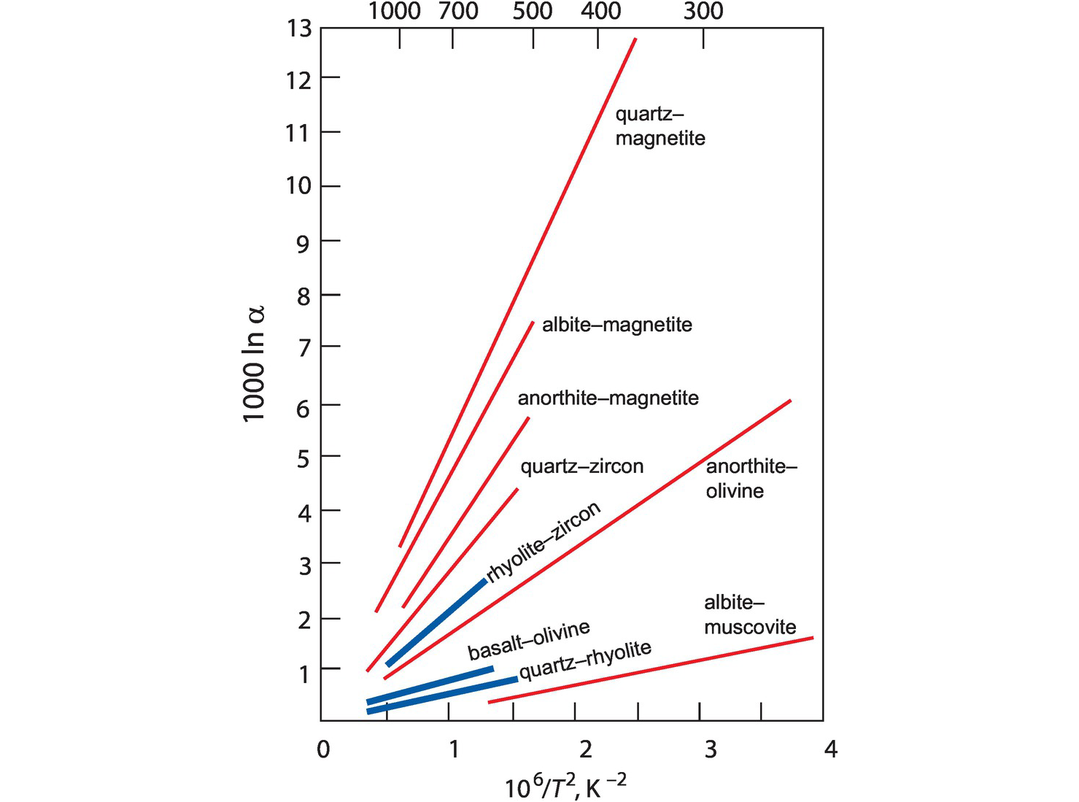

the heavier isotope will partition into the mineral with the higher ionic potential. In the case of the fractionation of 18O between quartz and magnetite, it is the quartz, which contains small highly charged Si4+, that is enriched in 18O, and the magnetite is 18O-deficient. The relationship between bond strength and isotopic fractionation was illustrated by Bindeman (2008), who gives the example of a granite at 850°C with a whole rock δ18O value of 7.8‰ which shows decreasing δ18O of its constituent minerals according to the increasing number of non-Si–O bonds in the mineral as follows:

It is evident from the above that the oxygen isotope composition of plagioclase is a function of its anorthite content.

It was shown in Eq. 7.5 that there is an important temperature control on isotopic fractionation leading to an obvious application in isotopic thermometry. Relative volume changes in isotopic exchange reactions, on the other hand, are very small, except for hydrogen isotopes, and therefore there is a minimal pressure effect. Clayton (1981) showed that at pressures of less than 20 kb the effect of pressure on oxygen isotope fractionation is less than 0.1‰ and lies within the measured analytical uncertainties. The absence of a significant pressure effect on stable isotope fractionation means that isotopic exchange reactions can be investigated at high pressures where reaction rates are fast and the results extrapolated to lower pressures.

There is also some evidence for crystallographic controls on isotope fractionation in minerals. Heavy isotopes are concentrated in more closely packed crystal structures as illustrated by the fractionation of carbon isotopes between diamond and graphite and 18O between α- and β-quartz. In calcite, crystal faces from different crystallographic forms have different isotopic compositions indicating that different surfaces in the same crystal can have slightly different bonding characteristics which are sufficient to fractionate the isotopes of oxygen and carbon (Dickson, 1991).

7.2.3 Kinetic Controls on Stable Isotope Fractionation

Kinetically controlled stable isotope fractionation reflects the readiness of a particular isotope to react and can be important in identifying particular physical and biological processes. For example, in a physical process such evaporation, an isotopically light molecule will have a slightly greater velocity than an equivalent heavy molecule. Kinetic isotope effects are often associated with fast, incomplete or unidirectional processes such as evaporation, diffusion and dissociation reactions, and unlike equilibrium processes they do not follow well-understood thermodynamic rules. Typically, they are more important in low-temperature geochemistry and are rarer at high temperatures. During distillation the light isotopic species is preferentially enriched in the vapour phase according to the Rayleigh fractionation law (Section 4.2.2) as is found in the fractionation of δ18O and δD in rainwater and ice.

When isotopic fractionation takes place as a result of diffusion, there is a kinetic effect whereby the light isotope is enriched relative to the heavy in the direction of transport indicating the mass dependence of this process (Watkins et al., 2017). At high temperatures diffusion-controlled isotopic fractionation can be important when interpreting the results of oxygen isotopes as thermometers or in experiments where high-temperature processes have not reached equilibrium. At lower temperatures isotopes can be fractionated by adsorption onto clay minerals in sediments. For example, isotopically lighter hydrogen, oxygen and sulphur may be preferentially adsorbed onto clay, leading to isotopic enrichments in formation waters (Ohmoto and Rye, 1979).

Kinetically controlled stable isotope fractionation is particularly important during biological processes and so is relevant to all the traditional stable isotope systems. Products from bacterial reactions tend to be enriched in in the light isotope because the dissociation energies are lower and bonds more easily broken. For example, the bacterial reduction of seawater sulphate to sulphide proceeds 2.2‰ faster for the light isotope 32S than for 34S. For the reactions

the rate constant k1 is greater than the rate constant k2 and the ratio k1/k2 = 1.022 (Rees, 1973). The effects of this fractionation in a closed system may be modelled using the Rayleigh fractionation equation (Section 4.2.2).

7.2.4 Mass-Independent Stable Isotope Fractionations

Some elements have more than two stable isotopes. For example, oxygen has three isotopes – 16O, 17O and 18O – and sulphur has four – 32S, 33S, 34S and 36S. Given that isotope fractionations are a function of the mass difference between the isotopes, we might expect the fractionation of 17O relative to 16O to be half that of 18O relative to 16O. Broadly, this mass-dependent fractionation is found to be the case, although with some minor differences because of the complex way in which fractionation factors relate to isotopic mass. For this reason the fractionation of 17O/16O relative to 18O/16O is 0.52, rather than precisely 0.5. However, there are some rare circumstances in which isotopic fractionation does not follow this pattern and instead represents the process of mass-independent fractionation. This has been found in the case of oxygen isotopes and sulphur isotopes where they occur in the upper atmosphere.

In geochemistry the recognition of mass-independent fractionation in the sulphur isotope system has huge importance. In this system mass-independent fractionation is quantified using the Δ-notation in the expressions

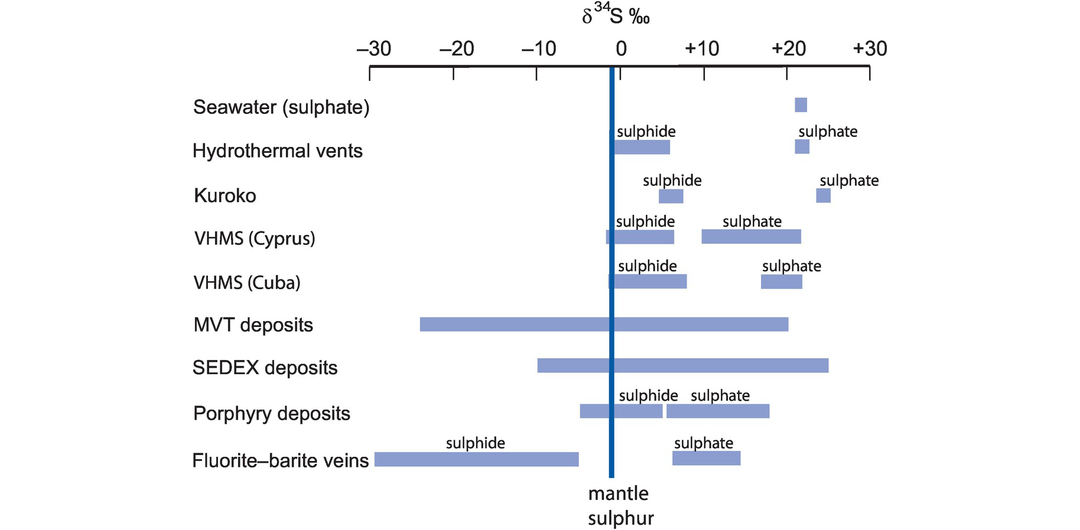

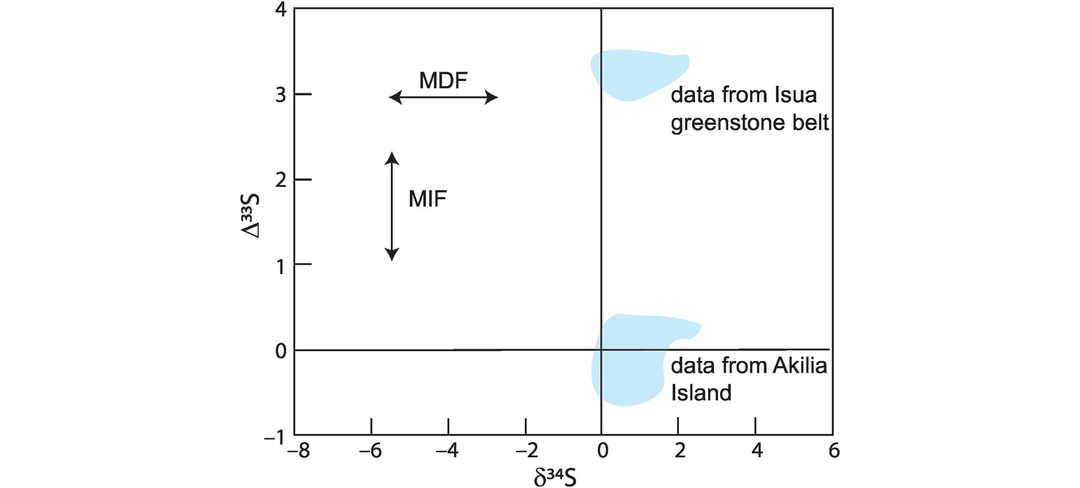

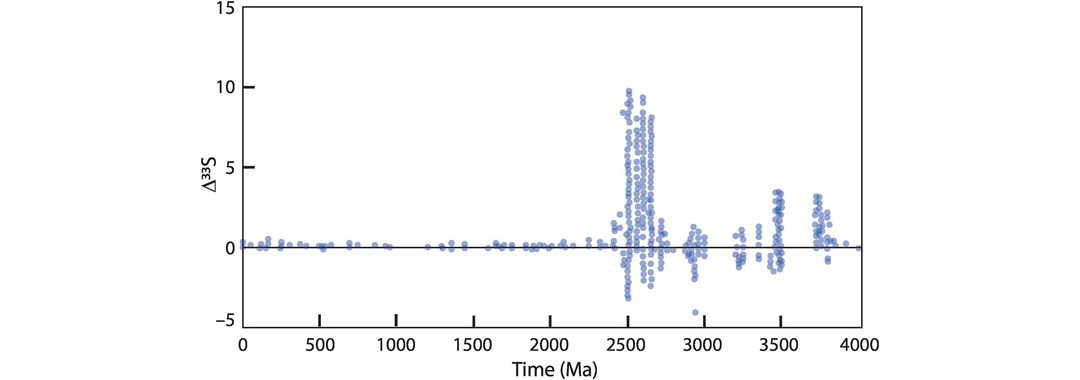

where 0.515 represents the fractionation of 33S to 34S and 1.91 represents the fractionation of 36S to 34S. These terms may be obtained by calculating the slope for pairs of measured δ3xS values in natural materials (see Farquhar and Wing, 2003, figure 2). In the modern Earth, Δ33S and Δ36S are zero, but in the early history of the Earth they have both positive and negative values (Farquhar and Wing, 2003). One helpful way of presenting the data is to plot a δ34S versus Δ33S diagram (Figure 7.24) as this shows the degree of mass-independent fractionation relative to that of mass-dependent fractionation.

Current thinking attributes the mass-independent fractionation of sulphur isotopes to photochemical reactions in the upper atmosphere (Ono, 2017); see Section 7.3.4.4. The changing pattern of mass-independent sulphur isotope evolution over time is therefore thought to relate to the chemical evolution of the Earth’s atmosphere. Experimental studies show that photolysis reactions in the ultraviolet range are capable of producing large mass-independent fractionations. This observation suggests that Earth’s ozone layer, which protects the planet from damaging ultraviolet radiation, was not present in the early Earth, supporting the view that the Earth’s early atmosphere was not oxygenic.

7.2.5 Clumped Isotopes

A relatively recent finding in stable isotope geochemistry is that there is a tendency for isotopologues containing rare heavy isotopes to concentrate more than one rare isotope in a given molecule. These ‘multiply substituted isotopologues’ have been termed ‘clumped isotopes’, the term ‘clumped’ indicating that two rare isotopes are bonded together (Eiler, 2007). The concentrations of such isotopologues are extremely low and present certain analytical challenges. In the past the assumption had been that the different isotopologues of a given molecule are randomly distributed according to their abundances in nature, whereas the recent finding is that heavy isotope isotopologues are more abundant than predicted from a purely random distribution. This can be explained by the preferential bonding of heavy isotopes in a given molecule leading to the ‘clumping’ of heavy isotopes into multiply substituted isotopologues at the expense of singly ubstituted isotopologues (Eiler, 2007).

Clumped isotope analysis uses the Δ notation to express deviation of the measured amount from that expected from the stochastic distribution. Values may be positive or negative. One of the most commonly measured values is the Δ47 value for CO2, which largely reflects variations in abundance of 13C18O16O = mass 47. The Δ47 value of CO2 can be calculated from the expression

where R47, R46 and R45 are the 47/44, 46/44, 45/44 ratios, respectively, for CO2 and R47*, R46* and R45* are the corresponding ratios if the sample had a stochastic distribution and are calculated from measured abundance ratios (see Eiler, 2007, for details). Inasmuch as clumped isotopes use the Δ notation, they might be considered similar to mass-independent isotope measurements. However, the two are very different. Clumped isotopes measure the deviation from the expected random distribution, whereas mass-independent isotope measurements record deviations from values expected from mass-dependent fractionation.

One of the main applications of clumped isotope studies is in low-temperature carbonate thermometry, giving rise to the field of ‘carbonate clumped isotope thermometry’. The formation of carbonate ions containing the heavy isotopes 13C and 18O is temperature-dependent but is independent of the fluid or mineralogical context in which the exchange reaction takes place. This allows, for example, foraminifera to be used to calculate former ocean temperatures (Meinicke et al., 2020). The novelty of this methodology means that it continues to develop both in the application of new technologies for the precise measurement of small isotopic difference and in the refinement of the equilibrium reaction to take account of impurities in the carbonate phases (Hill et al., 2020).

7.3 Traditional Stable Isotopes

7.3.1 Oxygen

The ‘vital statistics’ of oxygen isotopes, summarising the range of isotopes, the measured isotope ratio, the standards used and the range of natural compositions, are summarised in Box 7.1.

Oxygen is liberated from silicates and oxides through laser-fluorination and then reduced to CO2 at high temperature for measurement in a gas source mass spectrometer. In carbonates carbon dioxide is liberated with >103‰ phosphoric acid. When oxygen isotope ratios are determined in water, the sample is equilibrated with a small amount of CO2 and the oxygen isotope ratio in the CO2 is measured. From the known water–CO2 fractionation factor the 18O/16O ratio in the water is calculated. Isotopic measurements are carried out using gas source mass spectrometry with a precision of the order of 0.1‰ (Sharp, 2017). In situ oxygen isotope analysis is also routinely carried out by ion microprobe with a precision of 0.15–0.24‰.

In this section we consider the extent to which oxygen isotopes vary in nature, their use in high-temperature and low-temperature thermometry and their application to the understanding of magmatic processes. In particular, we consider the process of crustal contamination and how it might be demonstrated on oxygen isotope–radiogenic isotope diagrams.

7.3.1.1 Variations of δ18O in Nature

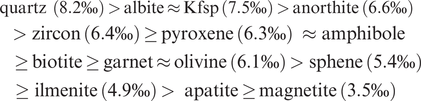

δ18O values vary in nature by about 100‰ with about half of this range occurring in meteoric water (Figure 7.1). Evidence from the analysis of ocean basalts indicates that the mantle δ18O value is 5.7 ± 0.2‰ (Bindeman, 2008), similar to the value for lunar basalts and constant over geological time (Taylor, 1980). The bulk δ18O value of chondritic meteorites is similar or slightly lighter than that of the Earth’s mantle. Felsic magmas show a broader and more positive range of δ18O values than is found in mafic and ultramafic rocks, and, similarly, sedimentary rocks and meta-sediments are isotopically heavier than mafic rocks and the mantle. Natural waters have very variable oxygen isotope compositions, as discussed below in Section 7.3.2.3, and some water types have strongly negative values relative to the VSMOW standard.

Stable isotopes and abundances

Measured isotope ratio

Standard

Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), which has an absolute 18O/16O ratio of 0.020052 (Baertschi 1976)

PDB: a belemnite from the Cretaceous Peedee formation of South Carolina (used for low-temperature carbonates)

Mantle value

Variations in nature

See Figure 7.1.

The distribution of oxygen isotopes in the major terrestrial reservoirs relative to the Earth mantle (δ18O‰ =5.7 ± 0.2 VSMOW).

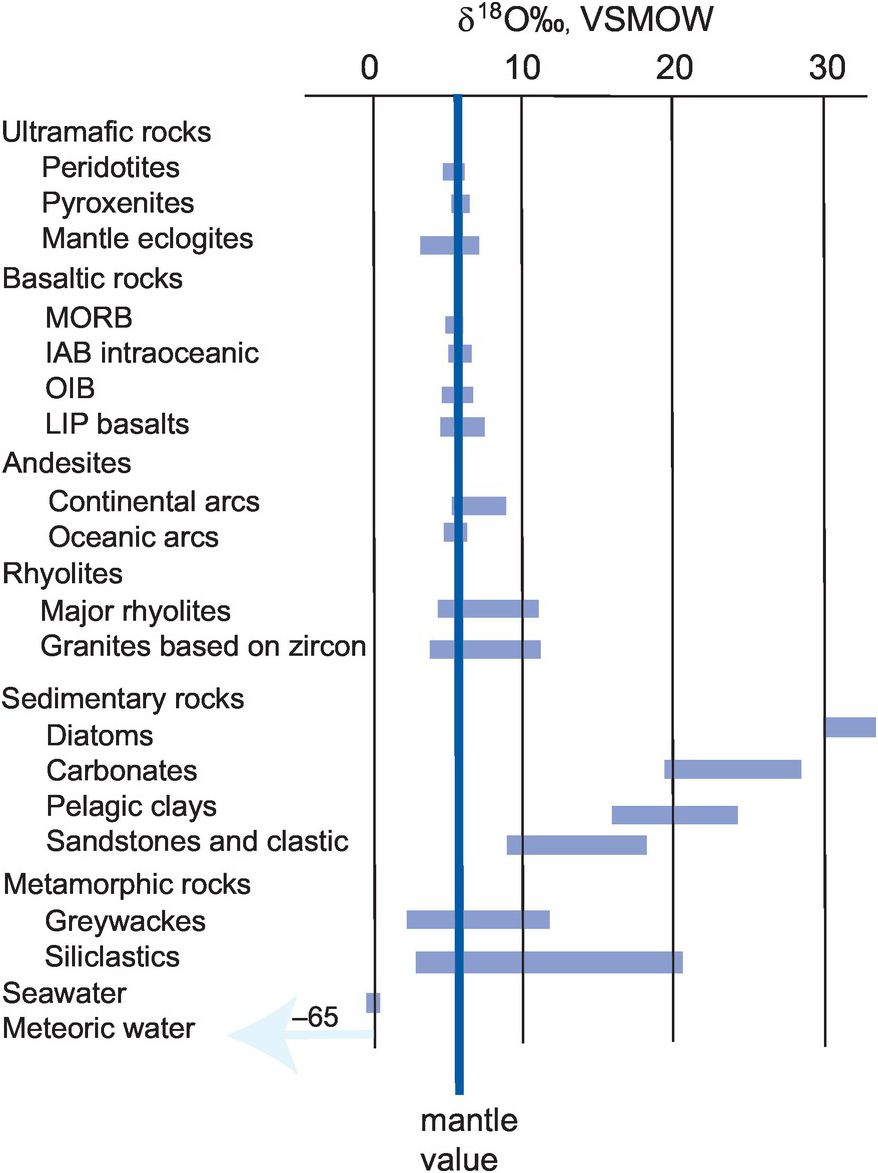

From these observations we can infer that crustal rocks with high δ18O values (i.e., those that are isotopically heavy) must have experienced some interaction with or were in part derived from high-δ18O metasedimentary silicate rocks such as meta-pelites or greywackes. Equally, there are a smaller number of crustal rocks which have unusually low δ18O values, that is, below mantle values. These are thought to represent samples which have interacted with a low-δ18O reservoir, the main contender for which is meteoric water. This interaction could be through the hydrothermal alteration of the parent rocks or the metamorphism and/or re-melting of hydrothermally altered source materials (Ryan-Davis et al., 2019). In both instances it is evident that rocks which deviate significantly away from mantle values must have experienced some interaction with materials at the Earth surface, illustrating the way in which oxygen isotopes can be a useful monitor of the process of crustal assimilation and contamination. This was demonstrated by Bindeman (2008), who showed that the assimilation of high-δ18O supracrustal materials and low-δ18O hydrothermally altered rocks gives rise to high- and low-δ18O magmas, respectively (Figure 7.2).

A δ18O versus SiO2 plot showing the field of mid-ocean ridge basalts (MORB) and the normal array of intermediate to felsic magmas. Also shown are the manner in which high-δ18O melts are produced by the assimilation of high-δ18O supracrustal materials and low-δ18O melts are the product of the assimilation of low-δ18O hydrothermally altered rocks.

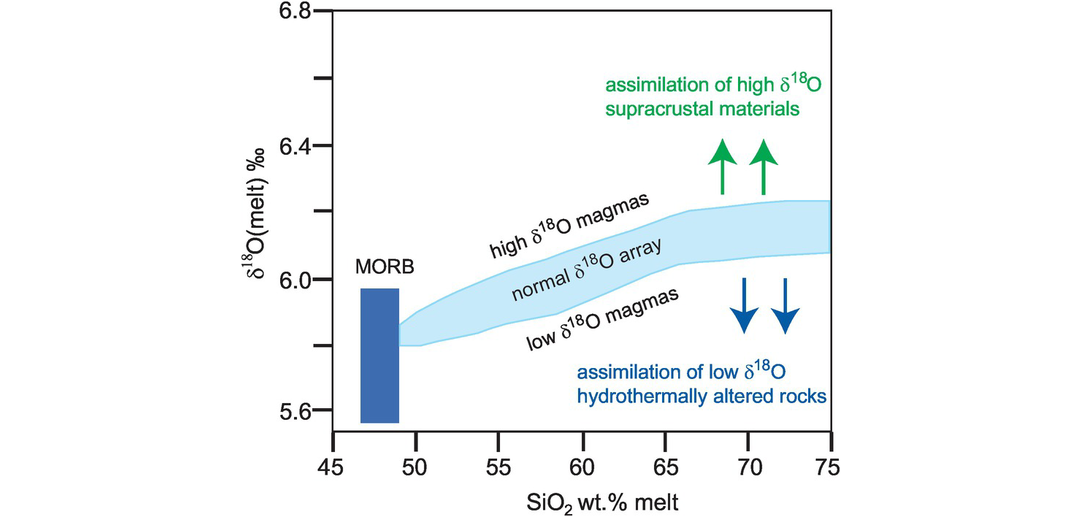

A particularly important means of recovering the δ18O value of a magma is through the measured oxygen isotope composition of the minerals zircon and quartz. This is possible because (i) these minerals preserve their δ18O even through high grades of metamorphism (Valley, 2003) and (ii) at high temperatures the fractionation of δ18O between zircon or quartz and melt is small (Figure 7.3). An empirical study by Bindeman and Valley (2002) suggests that the δ18O of a rhyolitic melt is about 2‰ higher than that of the zircon at ~750°C and slightly less at higher temperatures. Similarly, the δ18O of quartz almost mirrors that of the melt, in particular, at temperatures >850°C (Bindeman, 2008). This approach is particularly important in the study of detrital zircons where their magmatic provenance is unknown (Valley, 2003).

Fractionation factors expressed as 1000 ln α plotted relative to temperature shown as °C on the top axis and as 106/T2 Kelvin on the lower axis. Mineral–mineral fractionation factors are shown as red lines and mineral–melt fractionation factors as blue lines.

7.3.1.2 Oxygen Isotope Thermometry.

One of the first applications of the study of oxygen isotopes to geological problems was to geothermometry. In 1947 Urey suggested that the enrichment of 18O in calcium carbonate relative to seawater was temperature-dependent and could be used to determine the temperature of ancient ocean waters. The idea was quickly adopted, and palaeo-temperatures were calculated for the Upper Cretaceous seas of the Northern Hemisphere. Subsequently, a methodology was developed for application to higher-temperature systems based upon the distribution of 18O between coexisting mineral pairs. An excellent review of the methods and applications of oxygen isotope thermometry is given by Clayton (1981).

The expression summarising the temperature dependence of oxygen isotope exchange between a mineral pair was given above as Eq. 7.5 and is summarised in the expression

where T is in Kelvin and A and B are constants. Often the ‘B’ term is zero, making the fractionation factor simply a function of 1/T2.

Empirical observations indicate that a graph of ln α versus 1/T2 is linear over a temperature range of several hundred degrees (Figure 7.3) and a plot of this type for a pair of anhydrous phases should pass through the origin. Isotopic fractionations decrease with increasing temperature, and so oxygen isotope thermometers might be expected to be less sensitive at high temperatures. However, experimental studies are most precise at high temperatures (see, e.g., Clayton et al., 1989), and so thermometers have been calibrated for use with igneous and metamorphic rocks. Temperature estimates are most reliable for mineral pairs with large 1000 ln α values, such as the mineral pair quartz–magnetite (Figure 7.3).

(a) High-temperature applications of oxygen isotope thermometry. Initially, it was thought that oxygen isotope thermometry in igneous and metamorphic rocks had a number of advantages over conventional cation-exchange thermometry since there was the potential for oxygen isotopic exchange to be measured between many different mineral pairs in a single rock. However, subsequent studies have shown that the re-equilibration of oxygen isotopes between mineral pairs during cooling means that peak conditions in metamorphic rocks and magmatic temperatures in igneous rocks are not always recorded. This means that for oxygen isotope thermometry to reliably record high-temperature events, the minerals examined must be primary and unaltered; they must have not experienced exchange with a fluid phase; and the rock or magma cooled quickly so the measured isotope values are quenched and do not represent later diffusion. These conditions are rarely met for metamorphic and plutonic rocks, although they can be applied to fresh volcanic rocks containing quenched phenocrysts.

Several tests have been proposed for the reliability of oxygen isotope thermometry, the most useful of which is the concordance test and is based on the observation that there are potentially a large number of thermometers available in a single rock. The method uses mineral-pair measurements plotted on an isotherm plot in order to examine concordance between the different mineral-pair measurements and to assess the extent of isotopic equilibrium (Javoy et al., 1970; Huebner et al., 1986; Gregory et al., 1989). Isotopic equilibrium is measured relative to a straight line with a slope = 1.0, and any departure from this trend is indicative of isotopic disequilibrium.

Currently, the main application of high-temperature oxygen isotope thermometry is focused on refractory mineral pairs in which oxygen diffusion rates are low and which have seen no interaction with fluids. The selection of suitable mineral pairs therefore must be made on the basis of the expected temperature range to be determined in the light of diffusion rates and mineral closure temperatures (Valley, 2001). Suitable minerals include aluminosilicates, magnetite, garnet and rutile in quartzite, and magnetite, titanite and diopside in marble. In igneous rocks the minerals quartz and zircon may be used in silicic rocks and olivine in mafic rocks (Valley, 2001). A plot of measured and empirical mineral–mineral and mineral–melt fractionations versus temperature is shown in Figure 7.3, and a table of relevant fractionation factors is given in Table 7.1 (after Chacko et al., 2001, and Valley, 2003). A recent addition to these fractionation factors is the work of Lacroix and Vennemann (2015), who made an empirical estimate of the fractionation between quartz and Fe–Mg chlorites. They show that for the temperature range 240–550°C,

A coexisting quartz–orthopyroxene pair from a granulite facies metapelite (Huebner et al., 1986, sample Bb25c) has the following measured compositions:

The temperature dependence on the fractionation of 18O between quartz and pyroxene (we use the diopside value as an approximation) – see Table 7.1 and Eq. 7.5 – is

Since the δ value for quartz is >10.0, in this case we use Eq. 7.7

thus

and

From the thermometer equation (7.5)

(b) Low-temperature applications of oxygen isotope thermometry. The earliest application of oxygen isotopes to geological thermometry was in the determination of ocean palaeotemperatures. The method assumes isotopic equilibrium between the carbonate shells of marine organisms and ocean water and uses the equation of Epstein et al. (1953). This equation is still applicable despite some proposed revisions (Friedman and O’Neill, 1977):

where δc and δw are respectively the δ18O of CO2 obtained from CaCO3 by reaction with H3PO4 at 25°C and the δ18O of CO2 in equilibrium with the seawater at 25°C. The method assumes that the oxygen isotopic composition of seawater was the same in the past as today, an assumption which has frequently been challenged and which does not hold for parts of the Pleistocene when glaciation removed 18O-depleted water from the oceans (Clayton, 1981). The method also assumes that the isotopic composition of oxygen in the organism is the same as in seawater and ignores any species specific ‘vital effects’, and that there has not been any post-burial isotopic exchange with sediment pore water. Because the temperatures of ocean bottom waters vary as a function of depth, it is also possible to use oxygen isotope thermometry in palaeobathymetry to estimate the depth at which certain benthic marine fauna lived.

Using these methods, the careful analysis of deep sea sediment cores has allowed us to reconstruct past ocean temperatures and thus past climates over at least 800,000 years and shows the cyclicity of glacial and interglacial periods. Similarly, climatologists have recognised that continental glacial ice also preserves a long-term record of climate change, which shows the same cyclicity as seen in marine cores. In these studies both δ18O and δD (see Section 7.3.2) are used as temperature proxies. δ18O ice-core measurements are converted into temperature using a calibration based upon the linear relationship between annual values for δ18O and mean annual temperature at the precipitation site (Jouzel et al., 1997) in which δ18O becomes more negative with decreasing temperature. One such linear relationship for the Greenland Summit area gives the relationship δ18O‰ = −148.04 + 0.46403T (K). While this modern analogue method works best at middle to high latitudes, there are other local (geographic) and temporal factors that must be taken into account in order to obtain an accurate temperature estimate in other areas (Jouzel et al., 1997).

7.3.1.3 Oxygen Isotope–Radiogenic Isotope Correlation Diagrams

Correlations between radiogenic and oxygen isotopes are of particular importance because variations in the two types of isotope come about through totally different mechanisms and they are particularly important in recognising processes that involve contamination and mixing.

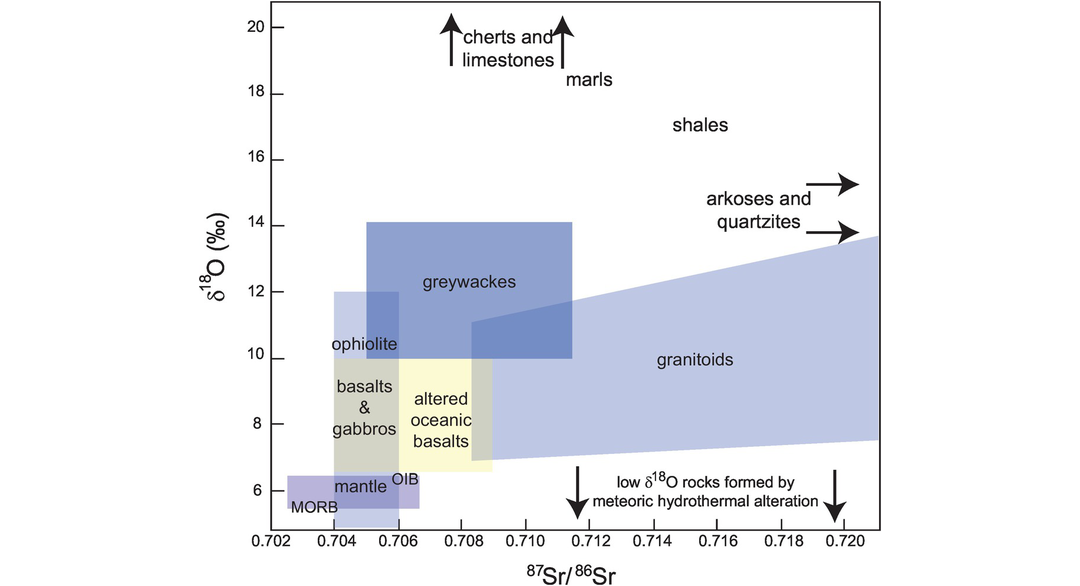

(a) Recognising crust and mantle reservoirs. Oxygen isotopes are a very effective way of distinguishing between rocks which formed in equilibrium with the mantle and those which formed from the continental crust. In general, the continental crust is enriched in δ18O relative to the Earth’s mantle (Figure 7.1). This has come about largely as a consequence of the long interaction between the continental crust and the hydrosphere and the partitioning of 18O into crustal minerals during low-temperature geological processes. Oxygen isotopes, therefore, are a valuable indicator of surface processes and a useful tracer of rocks which at some time have had contact with the Earth’s surface. Radiogenic isotopes, on the other hand, show differences between crust and mantle reservoirs which are a function of long-lived differences in parent–daughter element ratios and indicate the isolation of the reservoirs from one another for long periods of Earth history. This gives rise to crustal reservoirs which generally are enriched in 87Sr/86Sr and in radiogenic lead isotopes but depleted in 143Nd/144Nd and 176Hf/177Hf relative to the mantle. As an example, the range of combined oxygen and strontium isotopic compositions in common rock types is shown in Figure 7.4.

The indicative ranges of oxygen and strontium isotopes in common igneous and sedimentary rocks.

(b) Recognising crustal contamination in igneous rocks. Many crustal materials have oxygen and strontium isotope ratios which differ from mantle values (Figure 7.4) and so have the potential to provide evidence of the interaction between mantle rocks and the continental crust. This interaction may be through the contamination of mantle-derived melts in the continental crust or through the contamination of the source region by the subduction of crustal materials into the mantle. Details of the mixing processes are given by Taylor (1980), James (1981) and Taylor and Sheppard (1986).

The calculation of mixing curves entails some assumptions about the relative proportions of the parent element of the radiogenic isotope in the end-member compositions. In the case of strontium, when the contaminant in a source region is enriched in Sr relative to the mantle and forms a relatively small proportion of the whole, then contamination on a 87Sr/86Sr versus δ18O mixing diagram is characterised by the convex downward curvature of the mixing line. This arises because not only are crustal materials enriched in Sr relative to the mantle but their 87Sr/86Sr ratio is greater than that of the mantle and thus dominates any mixture of the two. Oxygen concentrations, however, are broadly similar in all rocks so that there is no large increase in the oxygen isotope ratio of the derivative melt. The small increase in δ18O is a simple linear function of the bulk proportion of crustal to mantle materials. In the case when the melt is enriched in Sr relative to the contaminant and the relative proportion of the contaminant is high, then compositions on a Sr–O isotope plot will define a mixing curve with a convex-up curvature (James 1981). This could be the case for a mantle-derived melt passing through the continental crust.

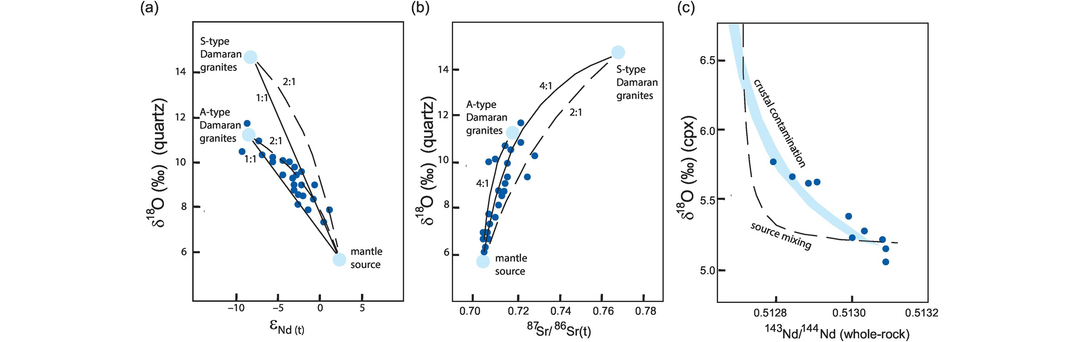

An example of the way in which source mixing has been inferred using oxygen and radiogenic isotopes is given by Trumbull et al. (2004). They show that 130 Ma, Cretaceous granites and related rhyolitic lavas from Namibia have a range of compositions that implies the mixing of mafic melts similar to those found in the Tristan mantle plume with a melt of lower crustal felsic rocks similar in composition to the A-type Damaran granites found in this region. A plot of δ18O in quartz versus the whole-rock Nd isotope composition, expressed as εNd, for a range of granitoids and felsic lavas lies on a mixing line between the probable mantle source and a lower crustal source (Figure 7.5a). A similar trend is seen on a plot of δ18O versus the Sr isotope composition of the melt at 130 Ma (Figure 7.5b) and illustrates the convex-downward mixing curve described above.

δ18O versus radiogenic isotopes. (a) Plot of δ18Oquartz versus εNd(t) for granitoids and felsic volcanic rocks (dark blue symbols) from Namibia. Source compositions for the mantle and two proxy crustal sources (Damaran granites) are shown in pale blue. Mixing lines between the mantle and crustal sources are constructed for the cases when the Nd concentrations in the crust and mantle are the same (1:1) and when the Nd concentration in the mantle is twice that in the crust (2:1). (b) Plot of δ18Oquartz versus (87Sr/86Sr)130Ma for granitoids and felsic volcanic rocks (blue symbols) from Namibia. Source compositions for the mantle and two proxy crustal sources are shown in pale blue. Mixing lines between the mantle and crustal sources are constructed for the cases when the Nd concentrations in the mantle are twice (2:1) and four times (4:1) that in the crust. The data in panels (a) and (b) do not support mixing between the mantle source and melts of a lower crystal source similar in composition to the S-type Damaran granites (after Trumbull et al., 2004; with permission from Elsevier). (c) Plot of δ18Oclinopyroxene versus (143Nd/144Nd)whole-rock) for arc-related lavas from the Kermadec–Hikurangi margin (after MacPherson et al., 1998; with permission from Elsevier). Arc lavas are shown as blue symbols; the pale blue curve is the calculated trend for models of the magma contaminated by continental crust. The dashed line is the calculated curve for mixing between depleted upper mantle and fluids derived from subducted oceanic crust. The data support the crust-contamination model.

MacPherson et al. (1998) sought to discriminate between mixing in the source region and crustal contamination in the Kermadec–Hikurangi convergent margin. Using δ18O in clinopyroxene as a proxy for the composition of melts, they showed that there is a linear trend between δ18O and whole-rock 143Nd/144Nd (in modern lavas this is the same as the mantle ratio). The results were compared with mixing curves for the contamination of the source region – the mixing of a depleted mantle peridotite with a fluid derived from altered subducted oceanic crust and sediment – and the contamination of basalt with crustal sediments. They showed that the shape of the curve defined by the data gave a better fit to the curves for crustal contamination than that calculated for mixing in the source (Figure 7.5c), indicating that the melts had interacted with sediments prior to eruption.

Source contamination is more easily recognisable in regions where there is no continental crust such as in oceanic basalts. This, however, has become possible only with improved resolution in oxygen isotope analysis, for the oxygen isotope variations may be small. Studies by Eiler (2001) showed that a small increase in δ18O (less than 1.0‰) in olivine in ocean island basalts correlated with increasing 87Sr/86Sr, implies a contaminated source.

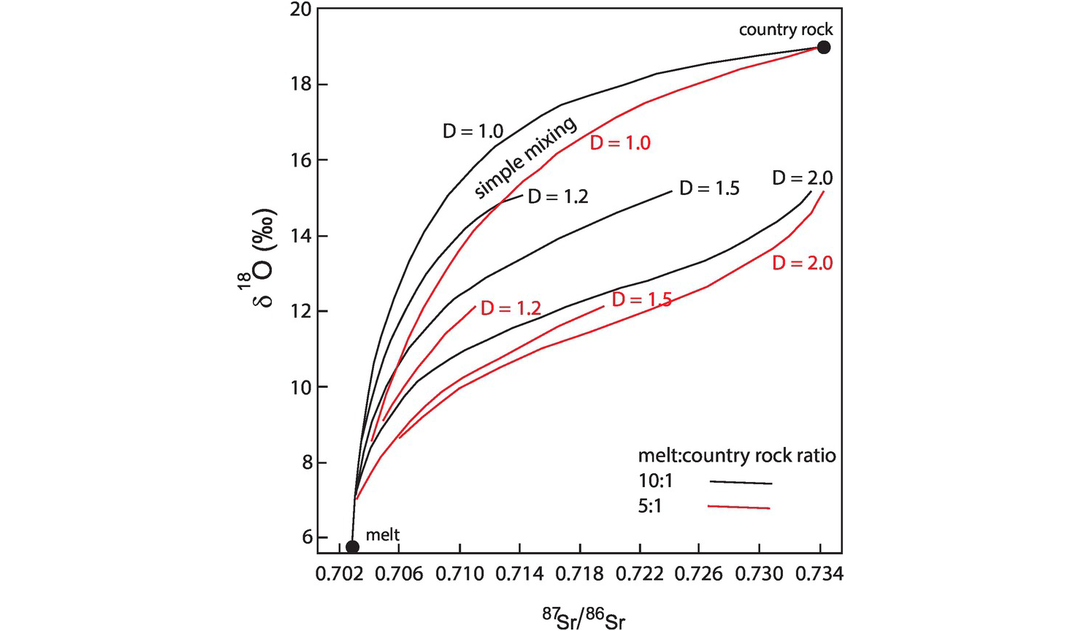

Finally, it is important to note that crustal contamination is rarely a simple mixing process and frequently involves three components: a melt, a precipitating cumulate phase and a contaminant (Taylor, 1980; James, 1981). This is the AFC process illustrated in Figure 7.6 for mixing between δ18O and 87Sr/86Sr from Taylor (1980). AFC processes, as opposed to simple mixing curves, are represented by a sigmoidal curve which does not extrapolate back to the position of either the source or contaminant.

Variation in δ18O with 87Sr/86Sr during assimilation and fractional crystallisation of a magma with δ18O = 5.7 and 87Sr/86Sr = 0.703 contaminated with a crustal component (country rock) with δ18O = 19 and 87Sr/86Sr = 0.735, for values of the partition coefficient (D) for Sr from 1 to 2. The black curves are for R = 0.1 (melt to country rock ratio = 10:1) and the red curves are for R = 0.2 (melt to country rock ratio = 5:1). The ratio of cumulates to assimilated country rock is 5:1.

(c) Recognising simple crystal fractionation in igneous rocks. An igneous system which has not suffered crustal contamination will exhibit the radiogenic isotope characteristics of the source, for radiogenic isotope ratios are not altered by crystal–liquid equilibria such as crystal fractionation. Oxygen isotopes, on the other hand, do show small changes in isotope ratio with crystal fractionation as is illustrated in Figure 7.2 and show a small increase in δ18O with increasing silica content. This decoupling between oxygen and strontium isotopes was documented by Chivas et al. (1982) in a study of a highly fractionated oceanic-arc plutonic suite in which oxygen isotope ratios increase from mantle values (δ18O = 5.4‰) in gabbros to δ18O = 7.2‰ in an aplite dyke, whereas 87Sr/86Sr ratios remain constant within the limits of error of their determination.

7.3.2 Hydrogen Isotopes and the Stable Isotope Geochemistry of Water and Hydrothermal Fluids

The element hydrogen is ubiquitous in nature in the forms H2O, OH−, H2 and as hydrocarbons. There are two isotopes of hydrogen: 1H and 2H, normally referred to as D (deuterium); isotope ratios are measured as the ratio D/1H, expressed as δD. Hydrogen isotopes show the largest relative mass difference between two stable isotopes with the result that there are large variations in measured hydrogen isotope ratios in naturally occurring materials.

The study of oxygen isotopes in conjunction with the isotopic study of hydrogen has proved to be a very powerful tool in investigating geological processes involving water. When plotted on a bivariate δD versus δ18O graph, waters from different geological environments are found to have very different isotopic signatures (Section 7.3.2.3). Hydrogen is a minor component of most rocks, and so, excepting when the fluid–rock ratio is very low, the hydrogen isotope composition of rocks and minerals is sensitive to the hydrogen isotope composition of interacting fluids. Oxygen, on the other hand, comprises 50‰ by weight (and in some cases more than 90‰ by volume) of common rocks and minerals and so is less sensitive to the oxygen isotope ratio of interacting fluids, except at very high fluid–rock ratios (Section 7.3.2.6).

7.3.2.1 Hydrogen Isotopes

The basic data for hydrogen isotopes are given in Box 7.3, and a summary of δD values for solar system bodies (Figure 7.7) and common rock types and waters (Figure 7.8) are also provided. Hydrogen is generated by heating minerals in a radio frequency (RF) induction furnace to liberate water from the mineral host. The water is then reduced to hydrogen in a furnace using zinc (Vennemann and O’Neill, 1993) or uranium.

Stable isotopes and abundances

Measured isotope ratio

In hydrology δD may be referred to as δ2H

In planetary studies δD may be expressed as D/H (the conversion factor uses the absolute value for D/H recorded below and Eq. 7.14)

Standard

Mantle value

δD‰ = −76 to −48‰ (average of 61‰); recommended value −60 ± 5‰ (Clog et al., 2013).

Bulk Earth δD‰ = −43

Variations in δD in the solar system

See Figure 7.7.

The range of hydrogen isotopes in solar system objects relative to the bulk Earth. (Data sources discussed in the text)

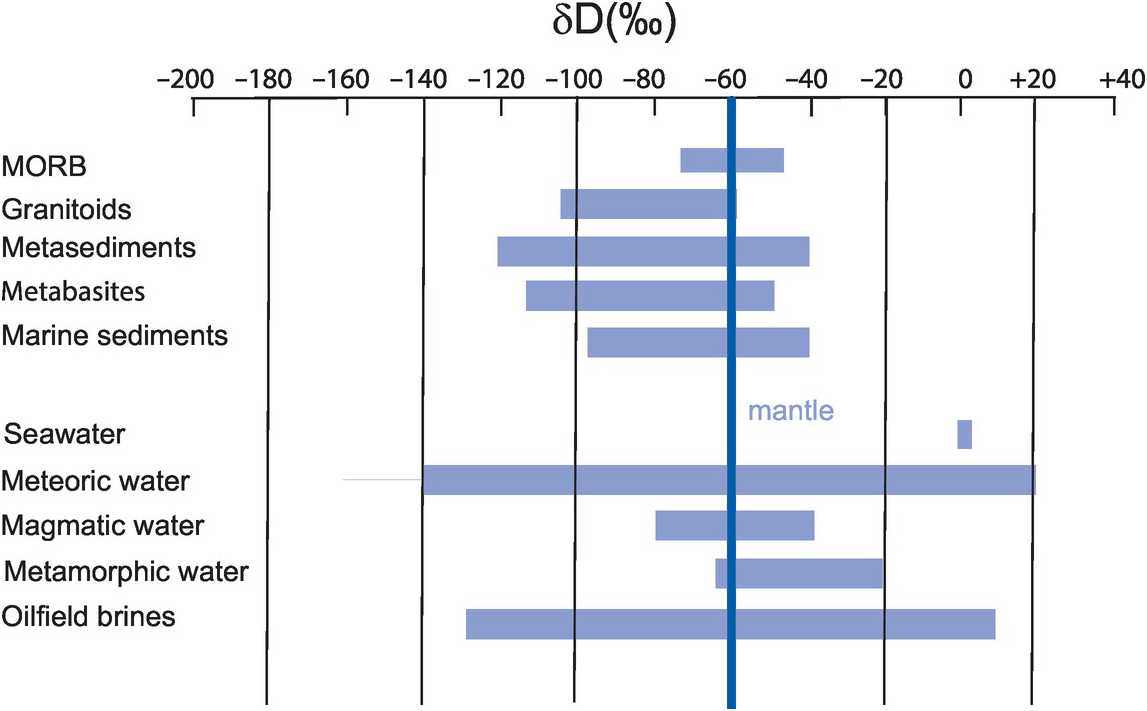

Terrestrial variation of δD.

See Figure 7.8

The range of hydrogen isotopes in some terrestrial reservoirs relative to the Earth’s mantle. (Data sources discussed in the text)

7.3.2.2 The Distribution of Hydrogen Isotopes in the Solar System

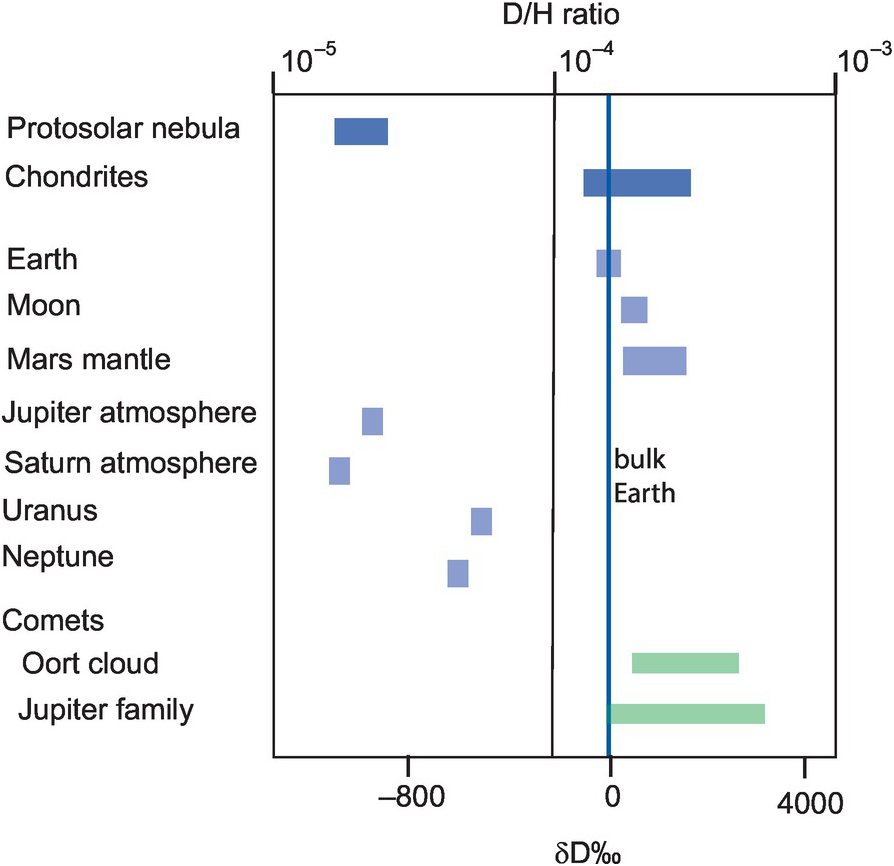

As might be expected, given the fundamental nature of hydrogen in the solar system, the fractionation of D/H between solar system objects is of considerable interest in planetary geochemistry, in particular, in the quest to understand the origin of water on the Earth and in other planetary bodies. There are now data from a number of solar system objects obtained by direct measurement from spacecraft and from spectral studies which show that the fractionations are very large with δD from < −800 to > +4000 and D/H varying over two orders of magnitude (Saal et al., 2013; Clarke et al., 2019). In planetary geochemistry D/H ratios are thought to indicate where in the solar system planets and different solar system objects formed. The protosolar nebula was isotopically light with D/H about 0.25 × 10−4, similar to the values recorded from the atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn. Values for the inner solar system, including Earth and Mars, are higher but define a narrow range of D/H ratios of ~1.5 × 10−4. The D/H of the bulk Earth is 1.49(± 0.03) × 10−4 (δD = −43) (Lécuyer et al., 1998), slightly lower than the Earth’s oceans (D/H = 1.56 × 10−4). Outer solar system comets have higher values ranging from Earth-like values to D/H ~5.0 × 10−4. Carbonaceous chondrite meteorites have δD values in the range −197 to +133‰, although CI chondrites have a narrower range of between +77 and +133 (Eiler and Kitchen, 2004). These values are shown in Figure 7.7, using data from Eiler and Kitchen (2004), Usui et al. (2012), Saal et al. (2013), Altwegg et al. (2015) and Clarke et al. (2019).

7.3.2.3 The Distribution of Hydrogen Isotopes in Natural Waters

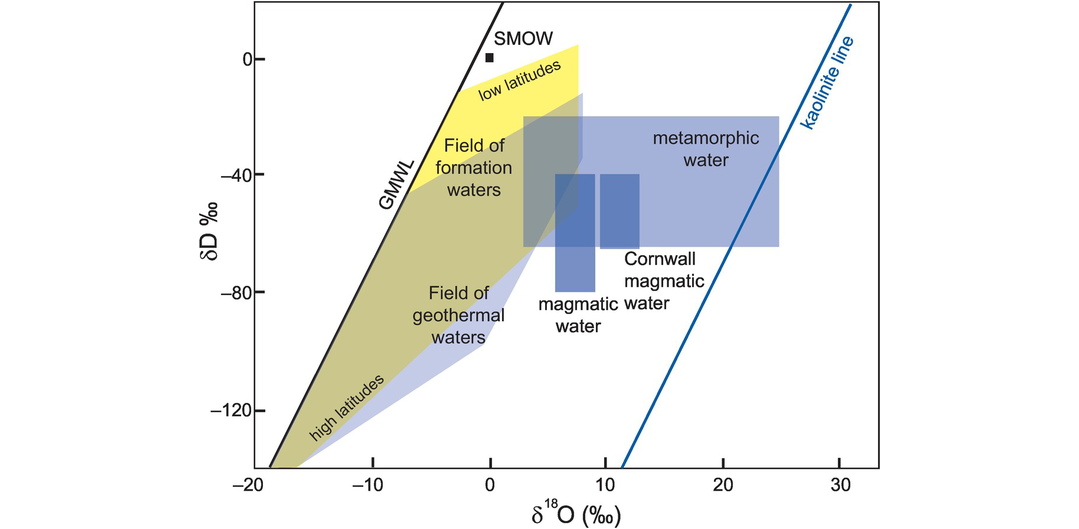

The isotopic composition of natural waters may be obtained either by direct measurement or by calculation from hydrous mineral phases using the method outlined in Section 7.3.2.5. Much of the work in this field was carried out in the 1960s and 1970s by Hugh Taylor’s group working at Caltech and is summarised in major contributions (Taylor, 1974; 1978). Taylor (1974) identifies six types of naturally occurring water which have a major influence on our thinking about hydrogeological processes, the compositions of which are summarised on a δD versus δ18O diagram (Figure 7.9). The isotopic character of the different types of water described here can be used to trace the origin of hydrothermal solutions.

(a) Ocean water. Standard Mean Ocean Water is the isotopic standard for both δ18O and δD; therefore, convention dictates that ocean water has δ18O = 0‰ and δD = 0‰. Exceptions to this rule are from areas such as the Red Sea which has elevated values of δ18O and δD created through high rates of evaporation, or from areas where seawater is diluted with fresh water. Muehlenbachs and Clayton (1976) suggested that the oxygen isotopic composition of ocean water is buffered by exchange with the ocean crust, a view which is strongly supported by the study of Gregory and Taylor (1981) on the distribution of oxygen isotopes in the Semail ophiolite, Oman (Figure 7.12).

Less certain is the isotopic composition of seawater in the past. Lécuyer et al. (1998) and Pope et al. (2012) calculated that in the very early Earth the mass of the oceans was greater by about 20‰, that the hydrogen isotope composition of seawater was lower than the present value by 20–30‰ but that the oxygen isotope composition was comparable to that of the modern oceans. In geologically more recent times there is evidence from the oxygen isotope composition of benthic foraminifera that there were global changes in the isotopic chemistry of the oceans during the Tertiary. In addition, data from marine sediment cores show that there were also changes to the oxygen isotope composition of the oceans during the Holocene brought about by the storage of isotopically light oxygen in ice in the polar regions, giving rise to isotopically heavier ocean water.

Plot of δD versus δ18O diagram for different water types. The fields of magmatic water, formation waters and geothermal waters are taken from Taylor (1974). The field for magmatic water from the granites of Cornwall is from Sheppard (1977). The metamorphic water field combines the values of Taylor (1974) and Sheppard (1981). The meteoric water line is from Craig (1961) and the kaolinite line from Taylor (1974).

(b) Meteoric water. Meteoric water shows the greatest variation in δD of all natural waters and the relationship between δD and δ18O is linear and quantified by Craig (1961) as:

δD and δ18O values for meteoric water vary according to latitude. Values are close to zero on tropical ocean islands, whereas at high latitudes in continental areas δ18O values are as low as −55‰ and δD values extend down to −440‰, although δD values below −160‰ are for polar snow and ice. Both the extreme variation and the linear relationship arise from the condensation of H2O from the Earth’s atmosphere. The extreme variation reflects the progressive lowering of 18O in an air mass as it leaves the ocean and moves over a continent. The linearity of the relationship, now known as the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL, Figure 7.9), indicates that fractionation is an equilibrium process and that the fractionation of D/H is proportional to 18O/16O. Subsequent studies identified deviations away from the GMWL, and some local meteoric water lines have slopes significantly different from the value of 8 due to local differences in temperature and humidity and kinetic effects during evaporation (Jouzel and Koster, 1996).

(c) Geothermal water. Modern geothermal water is meteoric in origin but isotopic compositions are transposed to higher δ18O values through isotopic exchange with the country rocks. δD values are the same as in the parent meteoric water or slightly enriched due to the non-equilibrium evaporation of water vapour (Figure 7.9). In contrast, ocean-floor geothermal systems are far more complex, particularly if methane is present, for they may host microbial communities which fractionate D/H to produce extremely light hydrogen with δD values < −400‰ (Konn et al., 2015).

(d) Formation water. Formation waters from sedimentary basins are usually saline and show a wide range in δ18O and δD values (Figure 7.9). The formation waters reported by Taylor (1974) are brines from oilfields. His results show that individual basins have water compositions which define specific linear trends representing mixing between meteoric water and either water from another source such as trapped seawater or the country rock. There is a decrease in the δD of formation waters at higher latitudes, further emphasising the link with surface meteoric waters.

(e) Magmatic water. The composition of magmatic waters is calculated from the isotopic compositions of igneous minerals (see Section 7.3.2.5). Particularly useful is the mineral muscovite, for at 800°C the isotopic composition of muscovite is the same as that of the water with which it is in equilibrium. The compositional range of magmatic water is quite well constrained for most igneous minerals and defines a very restricted field in δD–δ18O space, between −40 and −80‰ and +5.5 and +9.0‰, respectively (Taylor, 1974). Sheppard (1977), however, showed that the magmatic waters associated with the Permian granites in Cornwall, southwest England, plot in a different field with δD values of −40 to −65‰, and δ18O values of +9.5 to +13‰ (Figure 7.9). These granites are most probably the product of intra-crustal melting, and so the higher δ18O is inherited from a crustal protolith. This example highlights one of the ongoing difficulties in interpreting δD–δ18O data – that of differentiating between rocks whose source interacted with meteoric water prior to melting, that is, low-δ18O magmas, and those which interacted with meteoric water during or after emplacement. New advances in our understanding in this area have come from a study of δ18O in zircons; see, for example, Gilliam and Valley (1998) and Rumble et al. (2002).

(f) Metamorphic water. Our only access to the composition of metamorphic water is by back-calculating from the minerals present in the rock. In order to do this accurately, the temperature of the metamorphism must be known. Estimates of the δD and δ18O values of water in equilibrium with metamorphic minerals over a range of metamorphic grades have been made by Taylor (1974), Rye et al. (1976) and Sheppard (1981). A combination of these values gives a metamorphic water ‘box’ with δ18O values between +3 and +25‰ and with δD values between −20 and −65‰ (Figure 7.9). The relatively high δ18O values in some metamorphic rocks may suggest some inheritance from their sedimentary protoliths.

7.3.2.4 The Distribution of Hydrogen Isotopes in Terrestrial Reservoirs

The distribution of hydrogen isotopes from the upper mantle, the crust and clays associated with weathering is summarised in Figure 7.8 and in the discussion below.

(a) The depleted upper mantle. The δD value for the upper depleted mantle has been estimated from studies of magmatic water liberated from MORB. Early studies suggested a wide range of values but with the majority falling between −85 and −65‰ (Kyser and O’Neill, 1984). More recent measurements for the depleted upper mantle have revised these estimates and suggest a range between −76 and −48‰ with an average of 61‰ and a recommended value of −60 ± 5‰ (Clog et al., 2013). This value is close to that calculated by Lécuyer et al. (1998) for the bulk Earth of −40‰.

(b) Crustal lithologies. Other terrestrial reservoirs show a wide range of δD values, since frequently the whole-rock δD value of many terrestrial rocks is a composite value resulting from many different processes. In the case of igneous rocks, for example, processes such as magmatic degassing, crystal fractionation from a melt and sub-solidus interaction with meteoric water might all be superimposed on and thereby obscure the primary magmatic value. For this reason, the range of values for crustal lithologies shown in Figure 7.8 is not particularly useful as a discriminant.

Granitoids from the New England batholith, Australia, have δD values between −60 and −130 (O’Neill et al., 1997) and A-type granites from eastern China have δD = −59 to −145 (Wei et al., 2000). Meta-sediments have bulk rock δD values between −70 and −120 (Taylor, 1974), although lower values are recorded by Harris et al. (1997). Ultra-high-pressure (UHP) mafic rocks and felsic gneisses from the Dabie–Sulu orogenic belt in China have δD values in the range −74 to −100 (Chen et al., 2011). Lower-grade mafic and ultramafic rocks have a similar range of values (−51 to −115; Ikin and Harmon, 1983). In marine sediment δD values are in the range δD = −40 to −95 (Taylor 1974).

(c) Clay minerals in the weathering environment. There is strong relationship between the isotopic composition of kaolin in weathering zones and the coexisting meteoric waters such that it is possible to define a ‘kaolinite line’ sub-parallel to the GMWL in which, relative to meteoric waters, clays are enriched in δ18O and depleted in δD (Figure 7.9). The kaolinite line may be expressed as

The linear relationship suggests that the kaolin was formed in equilibrium with meteoric water (Taylor, 1974). In a similar way, the clay mineral smectite also forms a linear array on δ18O–δD diagrams, defining a ‘smectite line’. However, in this case the position of the smectite line is temperature-sensitive such that the distance between the GMWL and the smectite line increases with decreasing equilibration temperature and shifts towards higher δ18O values. The link between meteoric water and clay minerals means that the minerals kaolinite and smectite offer the potential to be palaeoclimatic indicators and allow for the calculation of the δ18O and δD of the meteoric water in which they were in equilibrium (Mix and Chamberlain, 2014). The temperature of kaolination can be calculated from the equation of Clauer et al. (2015):

7.3.2.5 Calculating the Isotopic Composition of Hydrothermal Fluids from Mineral Compositions

Most commonly, the δD and δ18O composition of a hydrothermal fluid has to be calculated from the isotopic composition of minerals which were in equilibrium with it using laboratory calibrations of equilibria between rock-forming minerals and water. More rarely, the isotopic composition of hydrothermal fluids can be measured directly as the fluid preserved in fluid inclusions (Ohmoto and Rye, 1974; de Graaf et al., 2019). Where isotopic compositions are calculated, it is necessary to show that there was a close approach to isotopic equilibrium between a given mineral and the original hydrothermal fluid. This is not always straightforward, for the diffusion rates of hydrogen isotopes may be up to 100 times faster than those for oxygen isotopes even in the same mineral (Kyser and Kerrich, 1991).

Experimental calibrations for both oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in a range of mineral phases are given in Tables 7.2 and 7.3, respectively, allowing the isotopic composition of a hydrothermal fluid to be fully specified. This calculation requires knowledge of the temperature of equilibration which may have to be estimated or measured independently from a technique such as fluid inclusion thermometry. An example of this approach is given by Hall et al. (1974, table 4) in a study of the origin of the hydrothermal fluids involved in the formation of the Climax molybdenum deposit, Colorado. In this study the temperature of the hydrothermal fluid was already known from fluid inclusion thermometry and the δ18O and δD composition of the water were calculated from the isotopic composition of muscovite and sericite using the experimental calibrations for muscovite–water. An example of the calculation is given in Box 7.4.

Data

δ18Omuscovite = +7.4‰

δDmuscovite = −91.0‰

Temperature = 500°C (from fluid inclusion thermometry)

Calculation of the oxygen isotope composition of the water

The equation for muscovite–water (O’Neill and Taylor, 1967; see Table 7.2) is

at 500°C

Since Δmuscovite-water = 1000 ln α

Calculation of the hydrogen isotope composition of the water

The equation for muscovite–water (Suzuoki and Epstein, 1976; see Table 7.3) is

at 500°C

Since Δmuscovite-water = 1000 ln α

| Mineral | T (°C)b | A | B | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barite | 100–350 | −6.79 | 3.00 | Friedman and O’Neill (1977) | ||

| Calcite | 0–700 | −3.39 | 2.78 | O’Neill et al. (1969) | ||

| Dolomite | 252–295 | −3.24 | 3.06 | Matthews and Katz (1977) | ||

| Quartz | 200–500 | −3.4 | 3.38 | Clayton et al. (1972) | ||

| 500–750 | −1.96 | 2.51 | Clayton et al. (1972) | |||

| 250–500 | −3.31 | 3.34 | Matsuhisa et al. (1979) | |||

| 500–800 | −1.14 | 2.05 | Matsuhisa et al.,(1979) | |||

| Alkali feldspar | 350–800 | −3.41 | 2.91 | O'Neil and Taylor (1967) | ||

| 500–800 | −3.7 | 3.13 | Bottinga and Javoy (1973) | |||

| Albite | 400–500 | −2.51 | 2.39 | Matsuhisa et al. (1979) | ||

| 500–800 | −1.16 | 1.59 | Matsuhisa et al. (1979) | |||

| Anorthite | 350–800 | −3.82 | 2.15 | O'Neil and Taylor (1967) | ||

| 400–500 | −2.81 | 1.49 | Matsuhisa et al. (1979) | |||

| 500–800 | −2.01 | 1.04 | Matsuhisa et al. (1979) | |||

| Plagioclase | 350–800 | −3.4 − 0.14 × An | 2.91 − 0.76 × An | O’Neill and Taylor (1967) | ||

| 500–800 | −3.7 | 3.13 − 1.04 × An | Bottinga and Javoy (1973) | |||

| Muscovite | 400–650 | −3.89 | 2.38 | O’Neill and Taylor (1967) | ||

| 500–800 | −3.1 | 1.9 | Bottinga and Javoy (1973) | |||

| Rutile | 575–775 | 1.46 | 4.1 | Addy and Garlick (1974) | ||

| Magnetite | 500–800 | −3.7 | −1.47 | Bottinga and Javoy (1973) | ||

| Kaolinite | 0–350 | −4.05 | 2.76 | Sheppard and Gilg (1996) | ||

| Smectite | 0–350 | −6.75 | 2.55 | Sheppard and Gilg (1996) | ||

| Illite | 0–350 | −3.76 | 2.39 | Sheppard and Gilg (1996) | ||

| Chlorite | 66–175 | For [Mg2.5Fe0.5(OH)6][Al1.5Fe1.5][Al, Si3O10][OH2] | ||||

| −11.97 + 2.67x + 2.93x2 − 0.415x3 + 0.037x4 ; where x = 103/T | Savin and Lee (1988) | |||||

| Mineral | T (°C) | A | B | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscovite | 450–800 | 19.1 | −22.1 | Suzuoki and Epstein (1976) |

| Biotite | 450–800 | −2.8 | −21.3 | Suzuoki and Epstein (1976) |

| Hornblende | 450–800 | 7.9 | −23.9 | Suzuoki and Epstein (1976) |

| Ferroan pargasite | 350–850 | −23.1 ± 2.5 | Graham et al. (1984) | |

| Ferroan pargasite | 850–950 | 1.1 | −31 | Graham et al. (1984) |

| Tremolite | 350–650 | −21.7 | Graham et al. (1984) | |

| 650–950 | 14.9 | −31 | ||

| Actinolite | 400 | −29 | Graham et al. (1984) | |

| Arfedsonite | Uncertain | −52 | Graham et al. (1984) | |

| Kaolinite/Dickite | 100–250 | 0.972-0.985 | Marumo et al. (1980) | |

| Sericite | 100–250 | 0.973–0.977 | Marumo et al. (1980) | |

| Chlorite | 100–250 | 0.954–0.987 | Marumo et al. (1980) | |

| Zoisite | 280–650 | −27.73 | −15.7 | Graham et al. (1980) |

| Epidote | <300 | −138.8 | 29.2 | Graham et al. (1980) |

| 300–650 | −35.9 + 2.5 | Graham et al. (1980) | ||

| All minerals | 1000 ln αmineral–water = 28.2 − (22.4 ∗ 106/T2) | Suzuoki and Epstein (1976) | ||

| + (2XAl – 4XMg – 68XFe), where XAl, etc., is the mole fraction of Al in biotite, muscovite or hornblende | ||||

a For the equation 1000 ln αmineral–water = A + (B ∗ 106/T2).

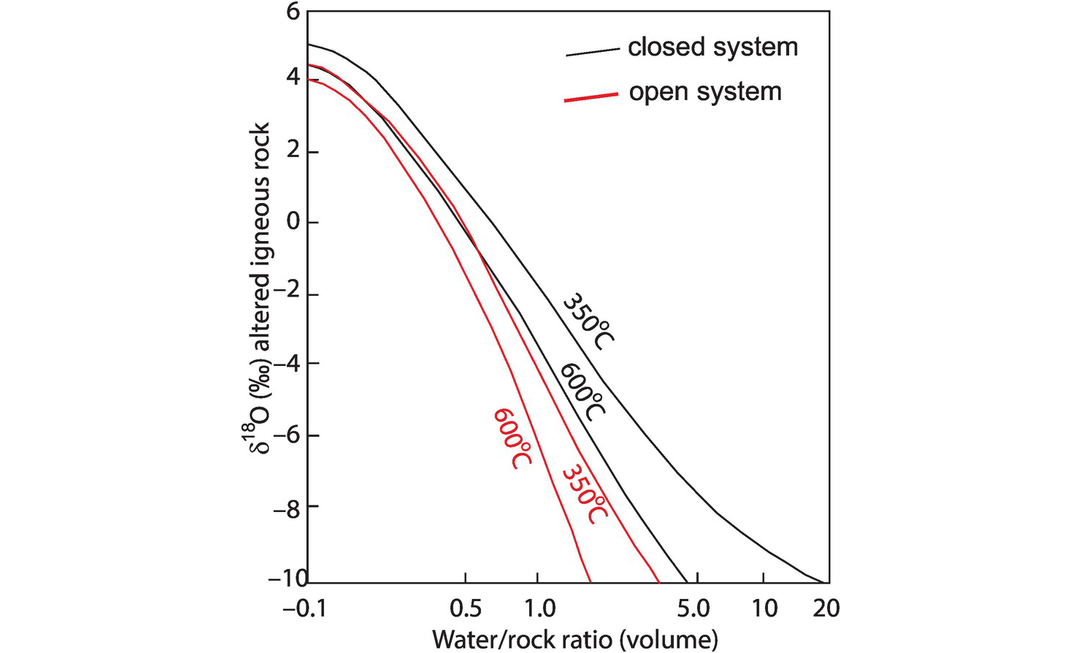

7.3.2.6 Quantifying Water–Rock Ratios

The geochemical effects of water–rock interaction can vary between two extremes. When the water–rock ratio is small, it is the δ18O in the rock that dominates the system and it is the fluid composition which is altered. On the other hand, when the water–rock ratio is large and the δ18O of the water dominates the system, then it is the δ18O value of the rock that is modified. Taylor (1974, 1977) derived mass balance equations from which the water–rock ratio may be calculated from δ18O values. For a closed system, from which no water is lost, the water–rock (W/R) ratio, integrated over the lifetime of the hydrothermal system, is:

This is the effective water–rock ratio which can differ from the actual water–rock ratio depending upon the efficiency of the exchange reaction. The initial value of the rock (δ18Orockinitial) is obtained from ‘normal’ values for the particular rock type (see Figure 7.1) or from an unaltered sample of the rock suite. The final value for the rock (δ18Orockfinal) is the measured value. The initial value for the fluid (δ18Oinitialfluid) is assumed (e.g., modern seawater) or in the case of meteoric water is calculated from D/H ratio of the alteration assemblage and the meteoric water equation. The composition of the final fluid (δ18Ofluidfinal) can be calculated from the mineralogy of the altered rock. This is sometimes done by using the approximation that δ18O plagioclase feldspar (An30) ~ δ18O rock, for feldspar is generally an abundant mineral in most rocks and exhibits the greatest rate of exchange between 18O and an external fluid phase. Provided that the temperature can be independently estimated, then the feldspar–water fractionation equation can be used to calculate the water composition (see the example below).

The equation for an open system in which the water makes only a single pass through the system is given by (Taylor, 1978) as

and the contrasting effects of open and closed systems on δ18O relative to the water–rock ratio are shown in Figure 7.10.

Plot of δ18O values in a hydrothermally altered rock calculated from the open-system water–rock ratio equation (Eq. 7.19) and the closed-system water–rock ratio equation (Eq. 7.18) (Taylor, 1974). The model assumes an initial δ18O value of +6.5 in the rock and an initial δ18O value of −14 in the water and curves are shown for 350oC and 600oC.

An example of how water–rock ratios may be calculated from oxygen isotope measurements is given in Box 7.5.

Data

Initial rock composition: δ18O = 6.5‰

Final rock composition: δ18O = −4.0‰

Initial fluid composition: δ18O = −14.0‰

Calculation of final fluid composition

The equation for plagioclase (An = 0.3) –water exchange from Table 7.2 is

at 500°C

Assuming δ18Ofsp ˜ δ18Owhole rock (final composition)

final fluid composition δ18O = −5.036‰

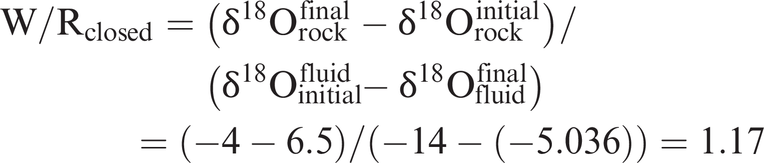

Water–rock ratio calculation

From the closed system equation (Eq. 7.18)

From the single-pass, open-system equation (Eq. 7.19)

Care should be taken in noting the units used for quantifying water–rock ratios, for both volume units and weight units are used. Both are shown in Figure 7.11. It is likely that any given hydrothermal system will behave some way between the two extremes of water-dominant and rock-dominant.

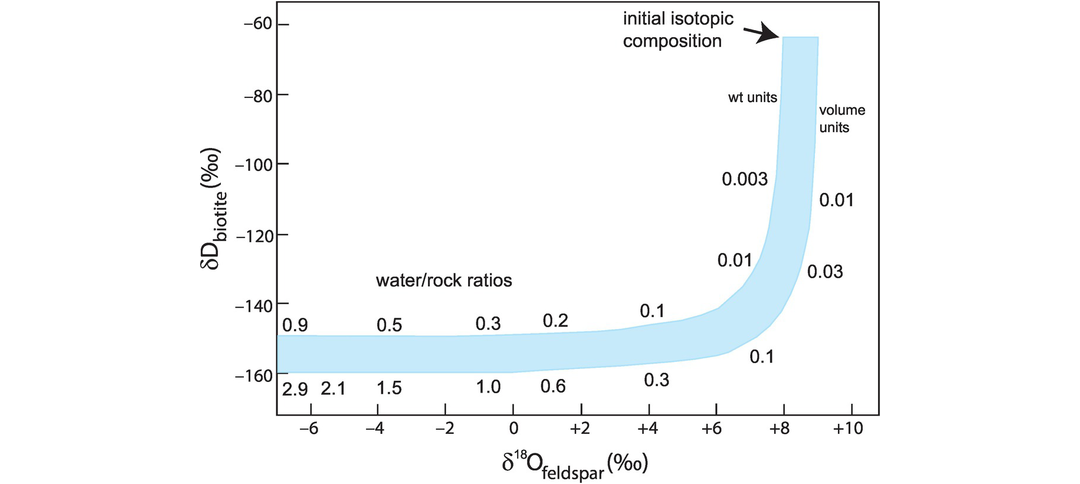

The effects on the isotopic composition of a hypothetical granodiorite pluton which crystallised under conditions of increasing water–rock ratio are shown on a δD versus δ18O plot in Figure 7.11, using the isotopic composition of biotite as a proxy for change in δD and the isotopic composition of feldspar as a proxy for change in δ18O (Taylor, 1978). At small water–rock ratios (up to 0.1 rock volumes) oxygen isotopic compositions are virtually unchanged, while δD values are reduced by about 100‰. As the water–rock ratio increases the δ18O value decreases rapidly at almost constant δD values. This is also illustrated in the study of Satir and Taubold (2001) on the Menderes gneiss complex in Turkey, who show that biotite is highly sensitive to the interaction of the gneiss with a very small amount of meteoric water and defines a trend of decreasing δD, while δ18O in feldspar remains constant as predicted by Taylor (1978).

δD versus δ18O diagram showing the isotopic change in D in biotite and δ18O in feldspar in a granodiorite undergoing isotopic exchange with groundwater. The plotted curve shows the range of δD and δ18O values with changing water–rock ratios. The curve was calculated for an initial feldspar composition of δ18O = +8.0 to +9.0, biotite δD = −65.0 and the groundwater δD = −120, δ18O = −16. The fractionation of D between biotite and water at 400–450 oC is given by Δbiotite–water = −30 and −40; the fractionation of δ18O between feldspar and water at 400–450 oC is given Δfeldspar–water = 2.0. A small water–rock ratio has a dramatic effect on the isotopic composition of δD in biotite, whereas higher water–rock ratios affect both δD in biotite and δ18O in feldspar.

7.3.2.7 Examples of Water–Rock Interaction

There are many applications of the combined hydrogen–oxygen isotopic system to the study of water–rock interactions, and in this section a range of illustrative examples is given. As has already been shown, the sensitivity of hydrogen and oxygen isotopes to hydrothermal solutions means that they are excellent tools for detecting hydrothermal alteration in otherwise fresh rocks. Further, they may be used to identify the origin of the water and quantify its volume relative to the country rock.

(a) Interaction between igneous intrusions and groundwater. In a number of pioneering studies, Taylor and his co-workers showed that high-level igneous intrusions are frequently associated with hydrothermal convective systems (see review by Taylor, 1978). They found that the country rocks surrounding such intrusions are massively depleted in δ18O and D relative to ‘normal’ values and that the minerals in both the intrusion and the country rock are isotopically out of equilibrium with magmatic values. They concluded that the isotopic effects were due to the interaction between the magma and meteoric water and proposed that the intrusion acted as a heat engine which initiated a hydrothermal convection cell in the groundwater of the enclosing country rocks. Water–rock ratios were found to vary from ≪ 1.0 to about 7.0. These studies brought an important insight into attempts to establish the original isotopic composition of igneous rocks, for samples showing evidence of interaction with meteoric water may not preserve primary stable and radiogenic isotopic compositions.

More recently, the examination of oxygen isotopes in zircon is leading to a re-evaluation of some claims of high-level crustal interaction between igneous intrusions and meteoric water. For example, Taylor and Forester (1971) showed that the Western Redhills granites on the Island of Skye, Scotland, were characterised by low-δ18O phases, implying interaction with meteoric water during emplacement. However, subsequent zircon studies made by Gilliam and Valley (1998) show that these granites are low-δ18O magmas and that any interaction with groundwater may have taken place in their source rather than during emplacement.

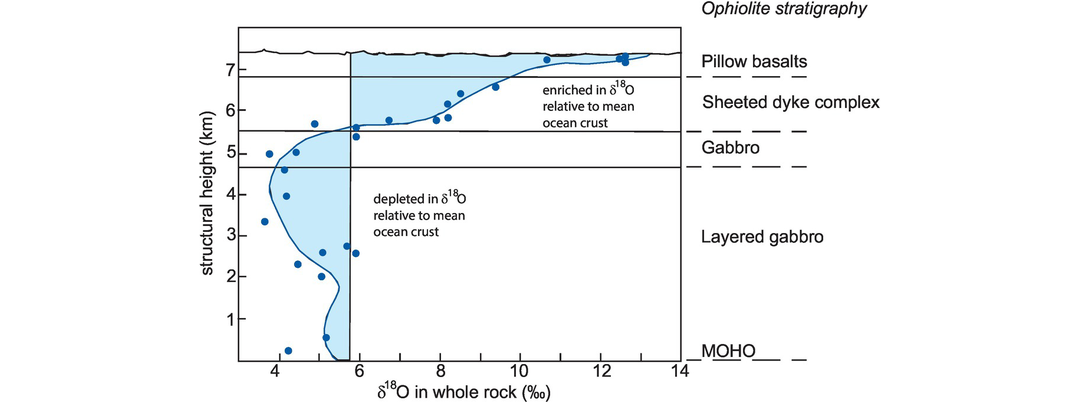

(b) Interaction between ocean-floor basalt and seawater. A large number of studies have shown that the rocks of the ocean floor, now preserved as ophiolites, have undergone massive seawater-hydrothermal exchange and alteration. In a now-classic study of the Oman ophiolite, Gregory and Taylor (1981) showed that upper layers (dykes and lavas) of the ophiolite were enriched in δ18O, whereas the lower gabbro and peridotite layers were depleted in δ18O relative to average ocean crust (Figure 7.12). This cross-over of values, at about 250°C, is due to the temperature-dependent partitioning of oxygen isotopes between silicate minerals and seawater. Later studies showed a similar pattern of alteration in the Indian Ocean floor (Stakes et al., 1984), confirming the general applicability of the Gregory and Taylor model. Subsequent studies on hydrogen isotopes from amphibole in oceanic gabbros suggest that the hydrothermal fluid may also contain a component of magmatic water in addition to seawater (Stakes, 1991). These studies led to the important observation that the net exchange of δ18O between seawater and the ocean crust in the Oman ophiolite was zero (Gregory and Taylor, 1981), suggesting that the δ18O composition of seawater is buffered by the composition of the ocean floor, a view subsequently confirmed by Campbell et al. (1988).

A whole-rock δ18O profile through the Oman ophiolite showing the relative enrichment and depletion in δ18O as a function of depth. Individual measurements are shown as solid blue circles.

(c) Water–rock interaction in metamorphic rocks. In metamorphic rocks oxygen isotopes are used to determine the patterns of fluid movement in a metamorphic sequence and establish the water–rock ratio. Fluid flow in metamorphic rocks may be pervasive, so that the fluid moves through pore spaces and establishes metamorphic equilibrium in the rocks (see, e.g., Chamberlain and Rumble, 1988), or may be channelised, migrating through cracks and fissures, in which case isotopic inhomogeneity may be preserved (see, e.g., Bottrell et al., 1990).

In addition, the combined study of hydrogen and oxygen isotopes can be used to determine the nature of the fluid originally in equilibrium with the metamorphic rock. Wickham and Taylor (1985) used this approach in their study of pelites in the French Pyrenees. They showed that the isotopic composition of muscovites had been homogenised through the influx of basinal formation waters which had exchanged their oxygen isotopes with the country rock.

(d) Water–rock interaction during the formation of hydrothermal ore deposits. An entire class of ore deposits is known to have formed from hydrothermal fluids. These fluids may be low or high temperature and associated with sedimentary, magmatic and, less commonly, metamorphic processes. Early studies such as that of Taylor (1974) were able to show the importance of oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in characterising these fluids and determining water–rock ratios. Indicative examples include the following:

Porphyry copper deposits. Qiu et al. (2016) use the composition of sericites plotted on a δD–δ18O diagram to show that the hydrothermal fluids in the Taiyangshan porphyry copper–molybdenum deposit of central China formed principally from magmatic fluids, with some small interaction with meteoric waters.

Kuroko-type massive sulphide deposits. A study of fluid inclusions in pyrite and chalcopyrite in Kuroko-type massive sulphide deposits from the Hokuroku district of Japan showed that their δD–δ18O compositions plot close to the composition of seawater which has experienced high-temperature isotopic exchange with the enclosing volcanic rocks (Ohmoto and Rye, 1974).

Mississippi Valley–type Pb–Zn deposits. Carbonate-hosted Pb–Zn sulphide deposits are thought to have formed in association with oilfield brines, although the origin of the brine is sometimes uncertain. A δD–δ18O study of fluid inclusions in sphalerite, fluorite and barite in the southern Appalachians showed that the brines originated as seawater but evolved to higher δ18O and lower δD by mixing with water that has reacted with organic matter (Kesler et al., 1997).

7.3.3 Carbon Isotopes

Carbon occurs in nature in its oxidised form (CO2, carbonates and bicarbonates), as reduced carbon (SiC, methane and organic carbon) and as the native element in diamond and graphite. Further, carbon is found throughout the whole solid Earth system from the core to the crust as well as in the oceans, atmosphere and biosphere.

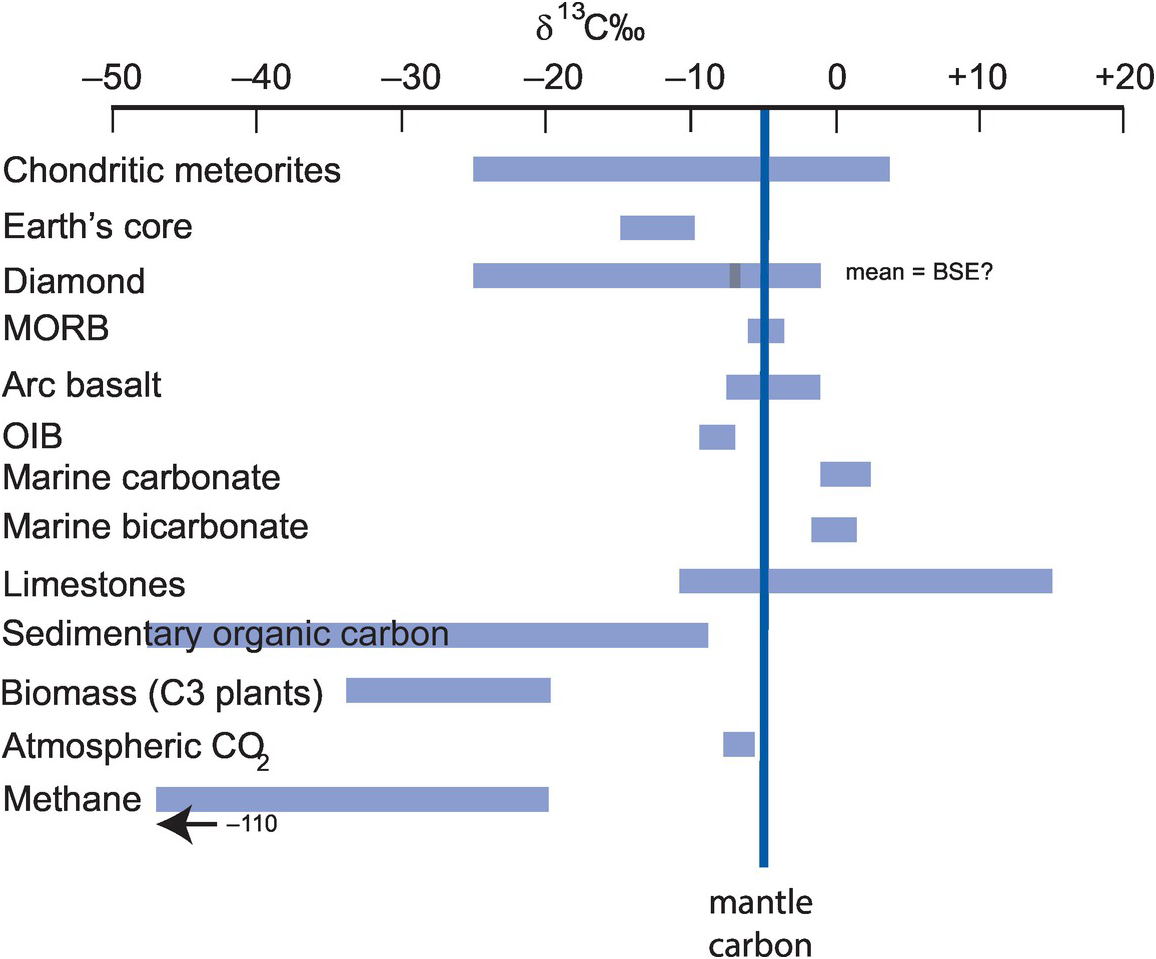

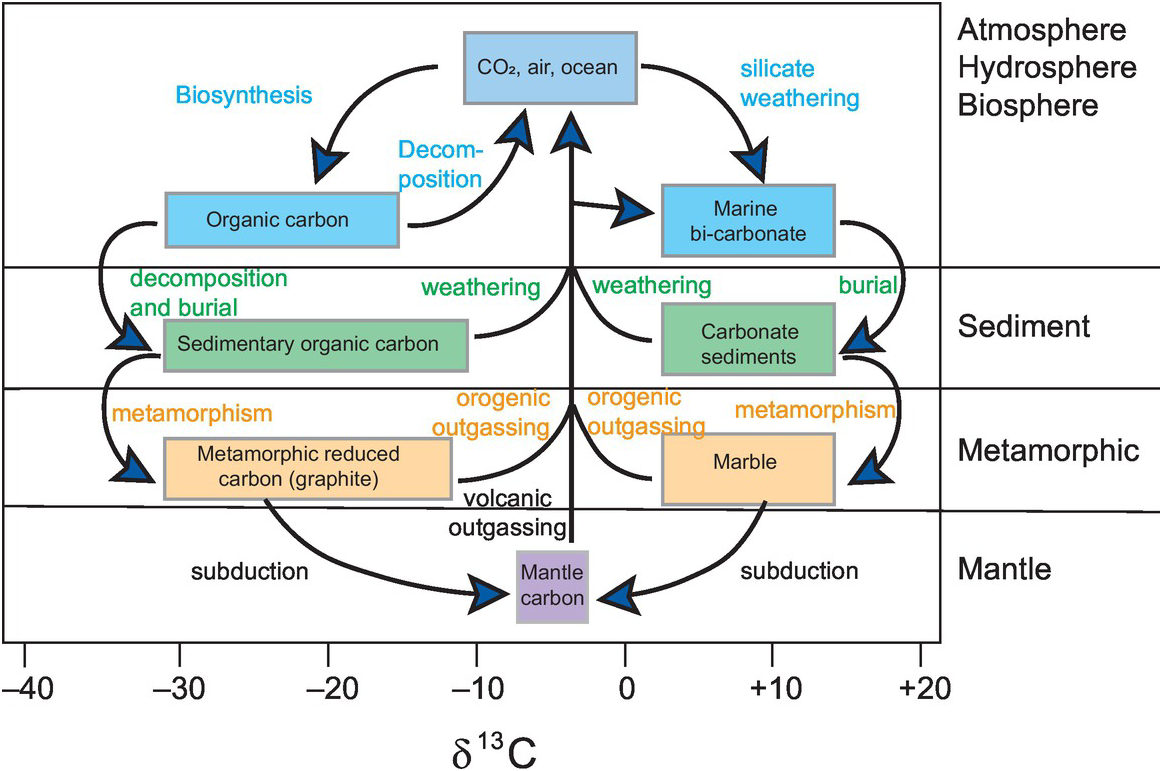

There are two isotopes of carbon, 12C and 13C; isotope ratios are measured as 13C/12C and expressed as δ13C‰ (Eq. 7.20). In natural systems carbon isotope compositions vary over 100‰. The essential data for stable isotopes of carbon are given in Box 7.6. Figure 7.13 shows the variation in δ13C in the major Earth reservoirs, and the main fractionations and their mechanisms in the global carbon cycle are shown in Figure 7.14 (after Suarez et al., 2019).

Stable isotopes and abundances

14C is a short-lived radioactive isotope with a half-life of 5730 years, produced by the action of cosmic rays on 14N in the atmosphere. It decays to 14N.

Measured isotope ratio

Standard

VPDB: Vienna Peedee belemnite from the Cretaceous Peedee formation of South Carolina, USA. This standard is used because its 13C and 18O values are close to those of average marine limestone. The original material of the PDB standard is now exhausted and current standard materials are a carbonatite NBS-18 and marine limestone NBS-19.

Mantle value

Bulk silicate Earth

Variations in nature

See Figures 7.13 and 7.14.

Variations in δ13C in the major Earth carbon reservoirs relative to the Earth’s mantle. (Data sources in the text)

The major Earth carbon reservoirs and the processes that control carbon isotope fractionations between them.

It is important to recognise the complexities of the Earth’s carbon cycle (Figure 7.14) inasmuch as it includes both the short-term surficial carbon cycle which operates on a time scale of a maximum of 10,000 years and the long-term deep-Earth carbon cycle which operates on a time scale of Ga. The short-term carbon cycle is focussed on the terrestrial biosphere and is concerned with exchanges between the biosphere, the atmosphere and the oceans. The deep-Earth carbon cycle is focussed on the emission of CO2 from volcanic sources; carbon drawdown through weathering, photosynthesis and carbonate formation; and the return of these materials to the mantle through subduction. Current estimates suggest that the present-day fluxes of CO2 into the mantle broadly match the amount released, implying that at the present time the mantle is at a steady state with respect to carbon (Rollinson, 2007). In this section we explore the role that carbon isotopes play in elucidating the balances in and between the surfical and deep-Earth carbon cycles.

Carbon isotopes are measured as CO2 gas, and precision is normally better than 0.1‰. CO2 is liberated from carbonates with >103‰ phosphoric acid or by thermal decomposition. Organic compounds are normally oxidised to CO2 at very high temperatures in a stream of oxygen or with an oxidising agent such as CuO. In situ measurements made by ion probe using secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) use a focused 133Cs+ primary beam. The impact of the 133Cs+ atoms sputters ions off the sample surface. Sputtered ions are accelerated in the mass spectrometer and are sorted by their mass/charge ratio before reaching an array of Faraday cup and electron multiplier detectors. Analyses are made using an appropriate running standard (Denny et al., 2020).

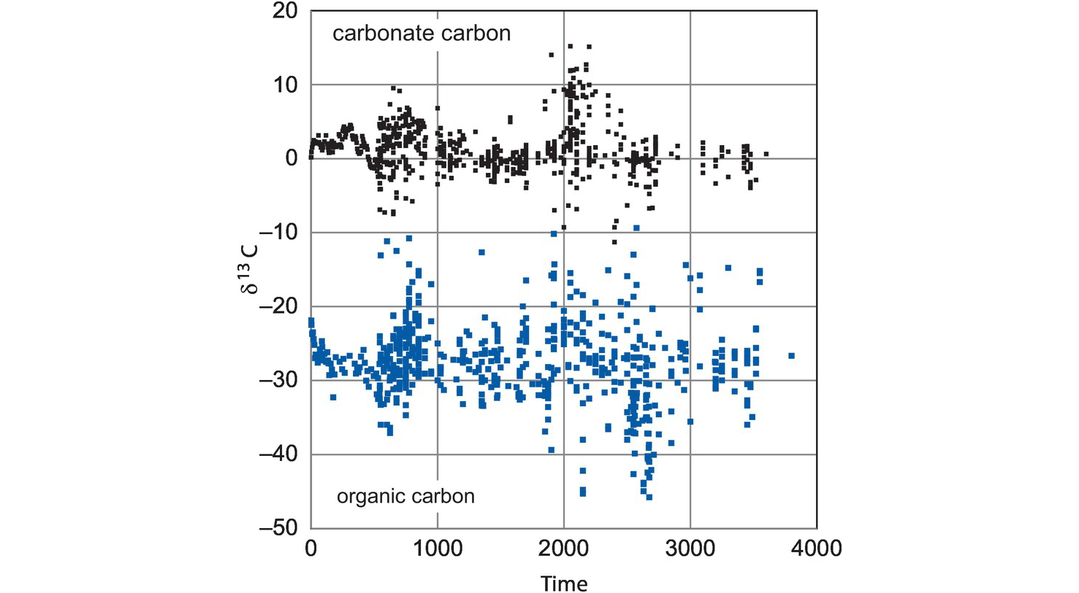

7.3.3.1 Controls on the Fractionation of Carbon Isotopes

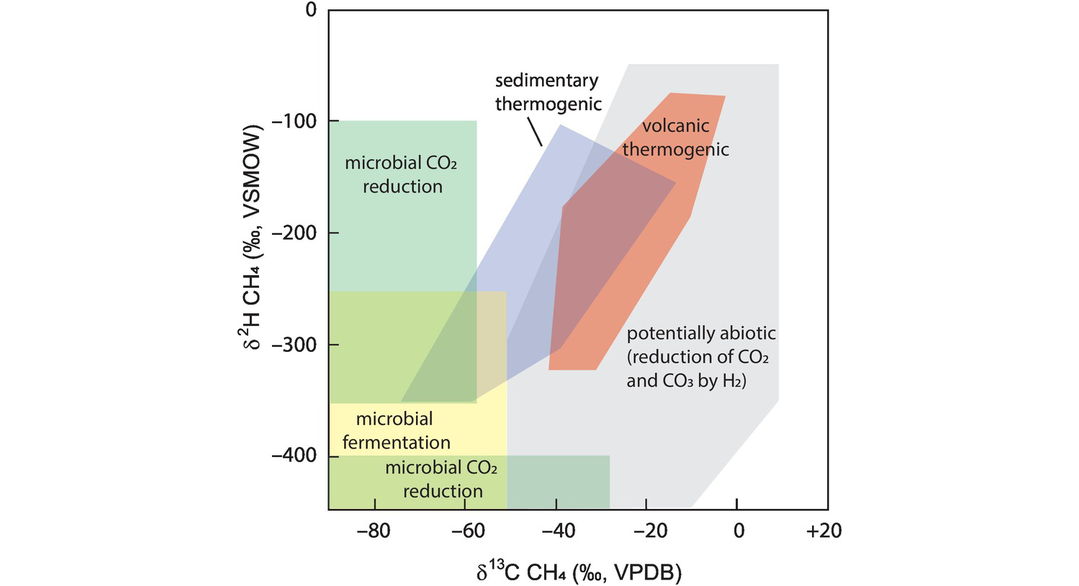

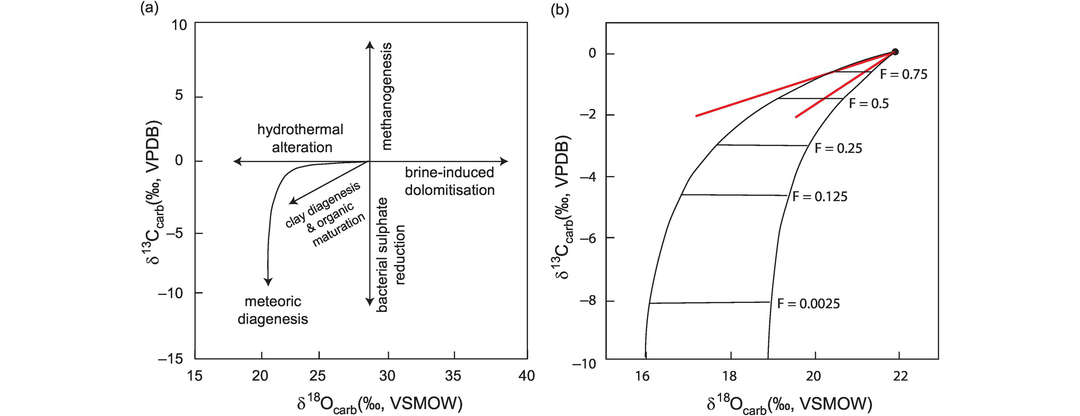

The fractionation of carbon isotopes is controlled by both equilibrium and kinetic processes. Equilibrium fractionation factors for carbon isotopes for a range of carbon-bearing species relative to CO2 are shown in Figure 7.15. The fractionation factors (α) were obtained from both theoretical and empirical studies and are discussed by Chacko et al., 2001. It can be seen from the carbonate curves in Figure 7.15 that at relatively low temperatures carbonate precipitated from CO2 is enriched in 13C, whereas at higher temperatures the carbonate is depleted in 13C. At very high temperatures the fractionation factors converge and so at mantle temperatures (~1000°C) carbon isotope fractionation between coexisting C-bearing species is small and less than 4‰ (Bottinga, 1969). Additional high-temperature fractionation curves include those for carbon-bearing species relative to carbides (Horita and Polyakov, 2015), and for atomic carbon (Deines, 2002). Fractionation factors between diamond and carbonate and diamond and carbon dioxide are given in Smit et al. (2016). At lower temperatures the fractionation of carbon isotopes between carbonates and organic carbon is such that δ13C values in organic carbon are on average 25‰ lower than in co-existing carbonate carbon (see Figure 7.16).

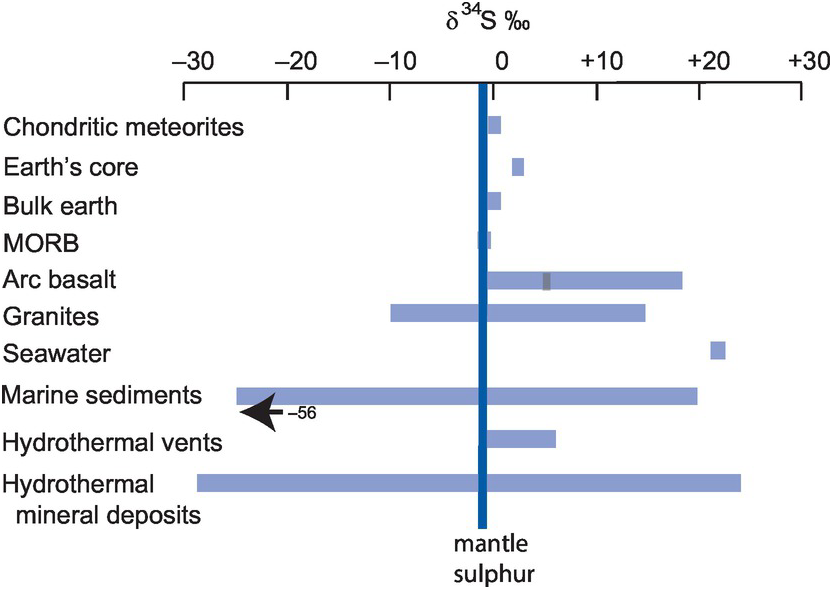

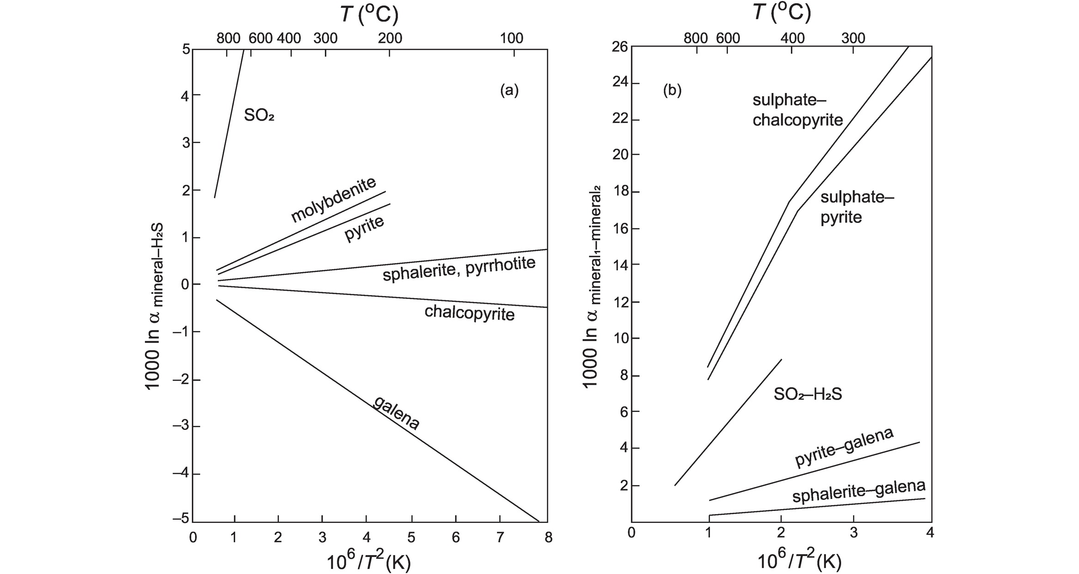

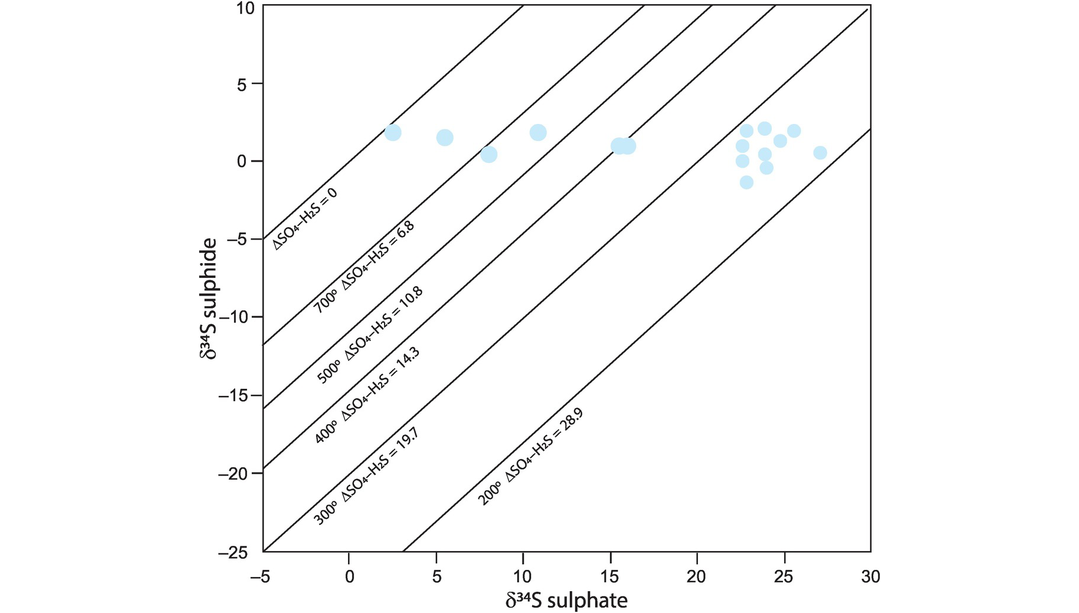

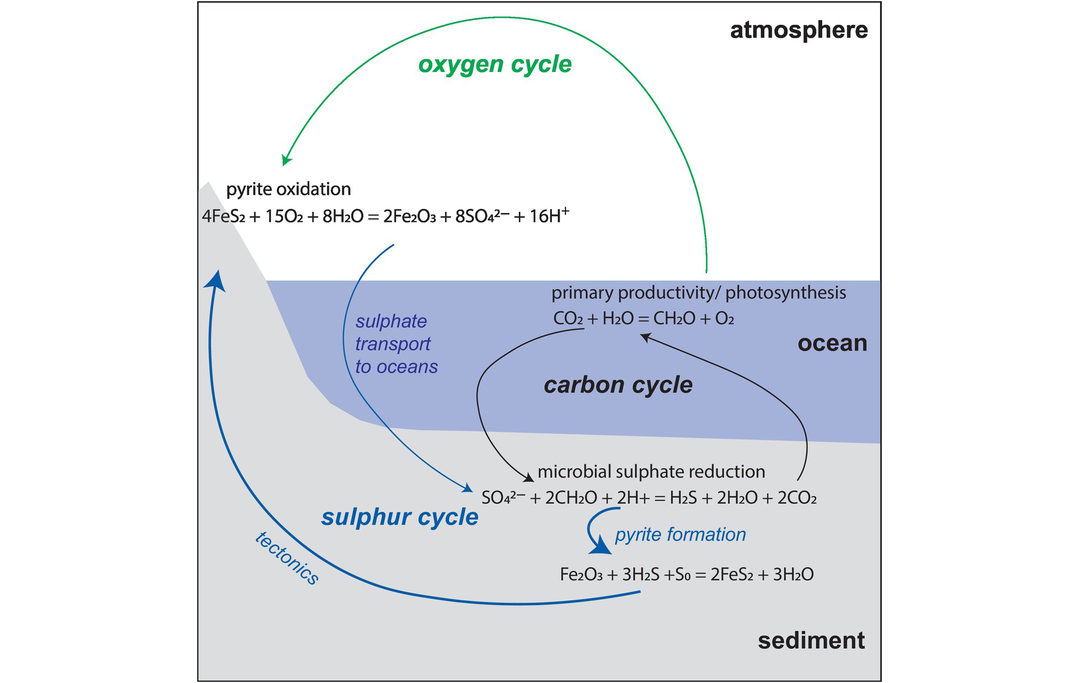

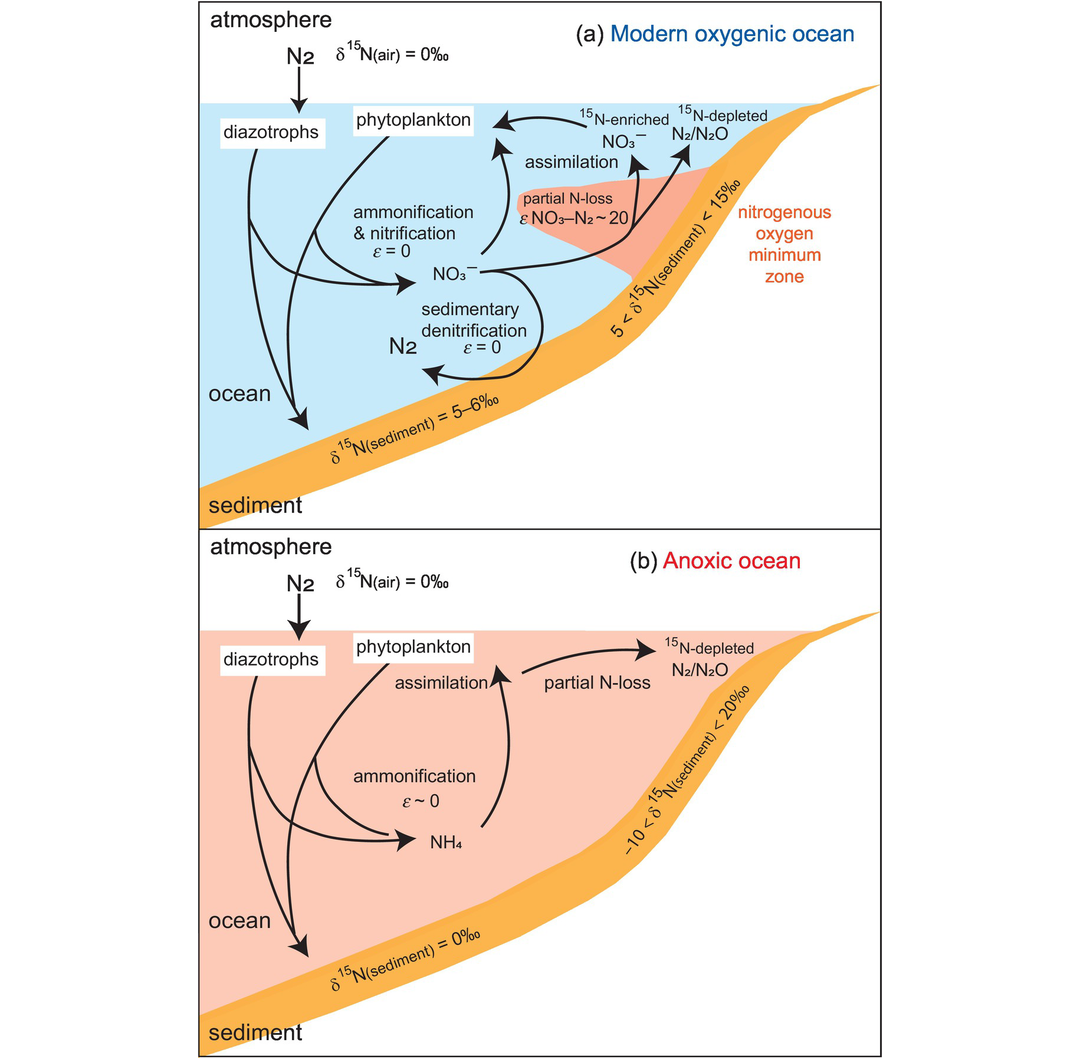

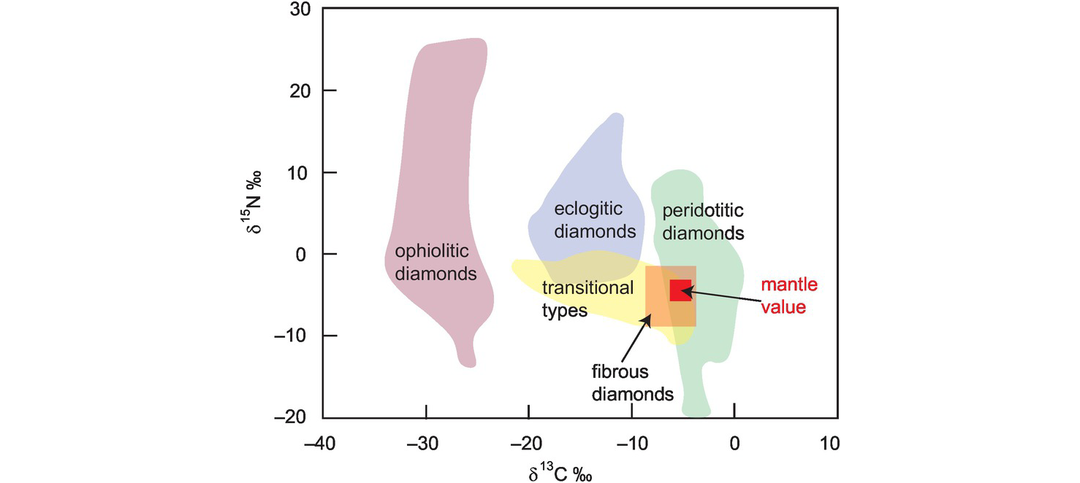

Fractionation factors shown as 1000 ln α for carbon species relative to CO2 versus temperature – shown as degrees C on the top axis and as 106/T2 Kelvin on the lower axis.